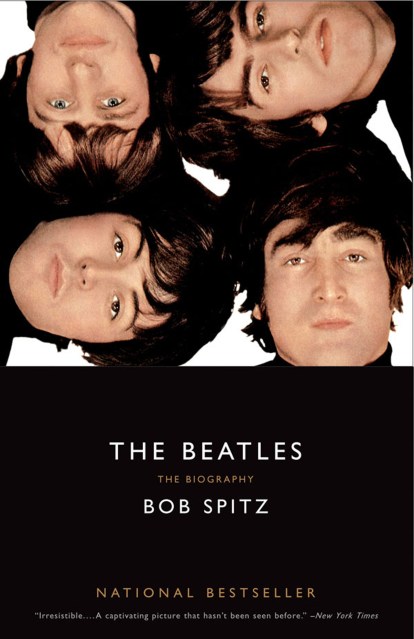

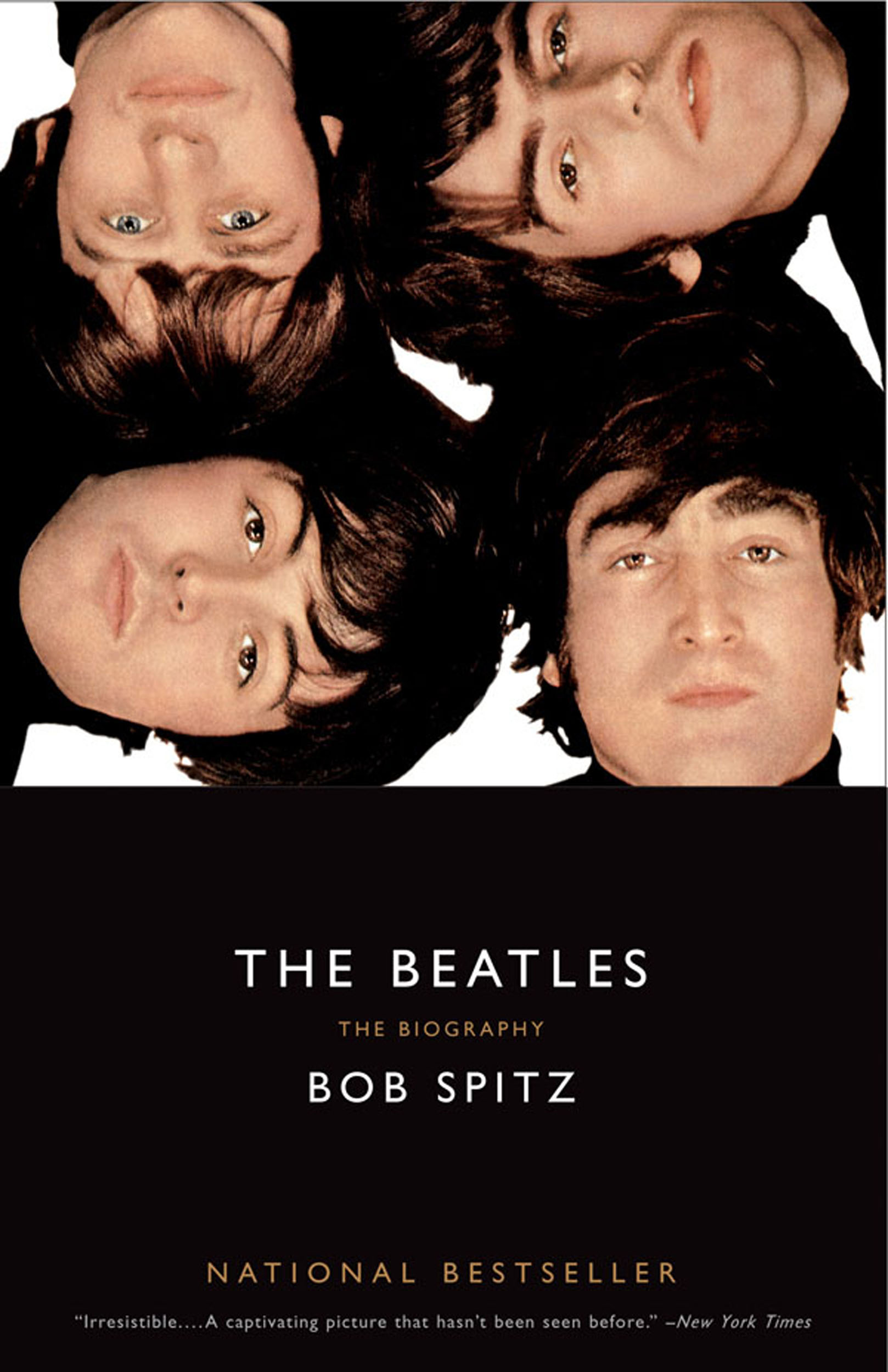

The Beatles

The Biography

Contributors

By Bob Spitz

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 25, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The definitive biography of The Beatles, hailed as “irresistible” by the New York Times, “riveting” by the Boston Globe, and “masterful” by Time.

As soon as The Beatles became famous, the spin machine began to construct a myth — one that has continued to this day. But the truth is much more interesting, much more exciting, and much more moving — the highs and the lows, the love and the rivalry, the awe and the jealousy, the drugs, the tears, the thrill, and the magic to never be repeated. In this vast, revelatory, exuberantly acclaimed, and bestselling book, Bob Spitz has written the biography for which Beatles fans have long waited.

As soon as The Beatles became famous, the spin machine began to construct a myth — one that has continued to this day. But the truth is much more interesting, much more exciting, and much more moving — the highs and the lows, the love and the rivalry, the awe and the jealousy, the drugs, the tears, the thrill, and the magic to never be repeated. In this vast, revelatory, exuberantly acclaimed, and bestselling book, Bob Spitz has written the biography for which Beatles fans have long waited.

-

"Irresistible...The Beatles amplifies and corrects some of what is known about the band's formative years. It shapes a particularly vivid picture of the young, surly John Lennon...It powerfully evokes both the excitement and the price of such a sudden rise...A captivating picture that hasn't been seen before."Janet Maslin, New York Times

-

"Masterly...A deep, serious, and accomplished account worthy of the most important band in the world...A book that, although exceptionally lengthy, is actually the perfect size...Spitz expertly captures the sense of time and place to frame his story."Tom Sykes, New York Post

-

"Richly detailed...The Beatles comes as close to being a quick read as any 983-page book has a right to be...Spitz also does a remarkable job capturing the distinct qualities of each Beatle."Jonathan Bor, Baltimore Sun

-

"Juicy, detailed, well-written, and authoritative...What makes Spitz's book a standout is his attention to visual detail...He has a knack for description and for cliffhangers. Every chapter of The Beatles promises more misery for the lads, more pleasure, more surprise."David Kirby, Atlanta Journal-Constitution

-

"Beatlemaniacs will swoon."People

-

"Riveting...Startlingly well-reported and consistently engaging...Even though the Beatles story is well known, Spitz has fleshed it out fully, revealing the flawed, singularly creative human beings behind the lovable moptop image....What Spitz does exceptionally well is contextualize."Carlo Wolff, Boston Globe

-

"In its scope, structure, and sheer length, this meaty 983-page true-life epic unfolds as a sort of Beatles's War and Peace...Spitz's genius is how he stitches together available Beatles knowledge with the artistry of a fine novelist."Michael Tarm, Cincinnati Enquirer

-

"Spitz has done a masterful job of focusing his kaleidoscope eyes on the greatest pop thing since Jesus."Richard Gehr, Village Voice

-

"Spitz knows his subject. His encyclopedic grasp pervades every page.Joe Selvin, San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Spitz marshals a staggering mass of research...The early chapters are irresistible; they have the hypnotic effect of a film clip run backward."Lev Grossman, Time

-

"Spitz has performed a valuable historical service...The Beatles respects its subjects without canonizing them...Best of all, at the end of the long and winding road, it sends us back home to the music."David Hinckley, New York Daily News

-

"Filled with intimate scenes...The first third of this opus is a treasure chest of revelation...Spitz demonstrates his deep research and writing chops by transporting us to the place where it all began...This book reminds us--in generous detail--that the Fab Four were just people."John Kehe, Christian Science Monitor

-

"A real page-turner...A vibrant and exhaustive factual and emotional picture of John, Paul, George, and Ringo's early life and times...It actually adds some new information--or at least a fresh analysis--to this often-told story...The lads's schoolboy years are told in captivating detail...Engagingly written, meticulously researched and documented, and tremendously insightful."Ruminator Review

-

"Fresh, terrifically entertaining...Packed with details and anecdotes that bring the Fab Four to life...Spitz's group portrait should now be considered the definitive Beatles biography."June Sawyers, Booklist

- On Sale

- Jun 25, 2012

- Page Count

- 992 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316031677

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use