By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

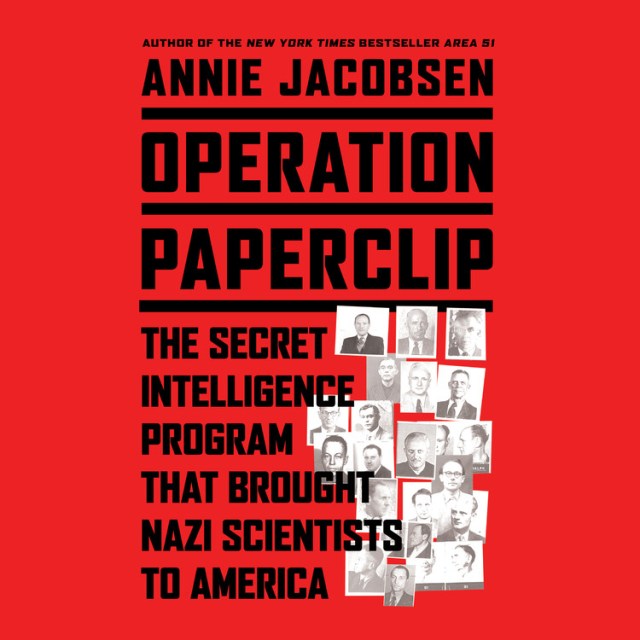

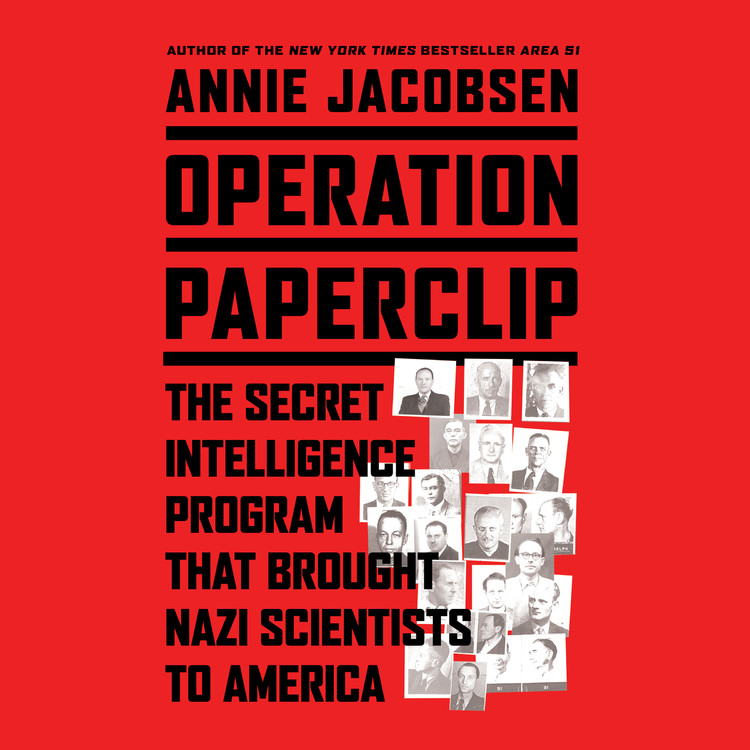

Operation Paperclip

The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America

Contributors

Read by Annie Jacobsen

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 11, 2014

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781619691544

Price

$38.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $49.00 $63.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 11, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The “remarkable” story of America’s secret post-WWII science programs (The Boston Globe), from the New York Times bestselling author of Area 51.

In the chaos following World War II, the U.S. government faced many difficult decisions, including what to do with the Third Reich’s scientific minds. These were the brains behind the Nazis’ once-indomitable war machine. So began Operation Paperclip, a decades-long, covert project to bring Hitler’s scientists and their families to the United States.Many of these men were accused of war crimes, and others had stood trial at Nuremberg; one was convicted of mass murder and slavery. They were also directly responsible for major advances in rocketry, medical treatments, and the U.S. space program. Was Operation Paperclip a moral outrage, or did it help America win the Cold War?

Drawing on exclusive interviews with dozens of Paperclip family members, colleagues, and interrogators, and with access to German archival documents (including previously unseen papers made available by direct descendants of the Third Reich’s ranking members), files obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, and dossiers discovered in government archives and at Harvard University, Annie Jacobsen follows more than a dozen German scientists through their postwar lives and into a startling, complex, nefarious, and jealously guarded government secret of the twentieth century.

In this definitive, controversial look at one of America’s most strategic, and disturbing, government programs, Jacobsen shows just how dark government can get in the name of national security.

“Harrowing…How Dr. Strangelove came to America and thrived, told in graphic detail.” —Kirkus Reviews

-

One of The Boston Globe's Best Books of 2014Matt Damsker, USA Today (4 stars)

One of iBooks' Top Ten Nonfiction Books of the Year

"Important, superbly written.... Jacobsen's book allows us to explore these questions with the ultimate tool: hard evidence. She confronts us with the full extent of Paperclip's deal with the devil, and it's difficult to look away." -

"With Annie Jacobsen's OPERATION PAPERCLIP for the first time the enormity of the effort has been laid bare. The result is a book that is at once chilling and riveting, and one that raises substantial and difficult questions about national honor and security...This book is a remarkable achievement of investigative reporting and historical writing."Boston Globe

-

"As comprehensive as it is critical, this latest expose from Jacobsen is perhaps her most important work to date.... Jacobsen persuasively shows that it in fact happened and aptly frames the dilemma.... Rife with hypocrisy, lies, and deceit, Jacobsen's story explores a conveniently overlooked bit of history." -- Publishers Weekly (starred)

-

"The most in depth account yet of the lives of Paperclip recruits and their American counterparts.... Jacobsen deftly untangles the myriad German and American agencies and personnel involved...more gripping and skillfully rendered are the stories of American and British officials who scoured defeated Germany for Nazi scientists and their research."New York Times Book Review

-

"Chilling, compelling, and comprehensive accounting.... Jacobsen's impressive book plumbs the dark depths of this postwar recruiting and shows the historical truths behind the space race and postwar US dominance. Highly recommended for readers in World War II history, espionage, government cover-ups, or the Cold War." -- Library Journal (starred)

-

"Darkly picaresque.... Jacobsen persuasively argues that the mindset of the former Nazi scientists who ended up working for the American government may have exacerbated Cold War paranoia."New Yorker

-

"An engrossing and deeply disturbing exposé that poses ultimate questions of means versus ends." -- Booklist (starred)

-

"Annie Jacobsen's Operation Paperclip is a superb investigation, showing how the U.S. government recruited the Nazis' best scientists to work for Uncle Sam on a stunning scale. Sobering and brilliantly researched." -- Alex Kershaw, author of The Liberator

-

"Throughout, the author delivers harrowing passages of immorality, duplicity and deception, as well as some decency and lots of high drama. How Dr. Strangelove came to America and thrived, told in graphic detail." -- Kirkus Reviews

-

"[A] gripping, always disquieting story of a nation forced to trade principle for power.... Jacobsen gives us many vivid moments.... OPERATION PAPERCLIPtakes its place in the annals of Cold War literature, one more proof that moral purity and great power can seldom coexist."Chris Tucker, The Dallas Morning News

-

"Jacobsen uses newly released documents, court transcripts, and family-held archives to give the fullest accounting yet of this endeavor." -- The New York Post

-

"Doggedly researched." -- Parade

-

"A compelling work with interesting historical and personal revelations."Jay Watkins, CIA's Intelligence in Public Literature

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use