By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

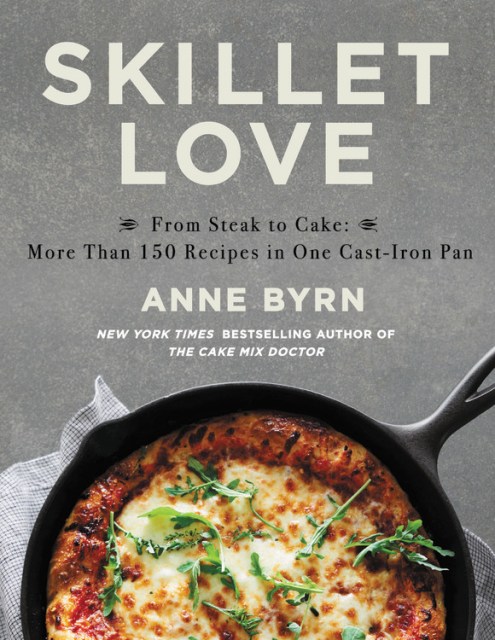

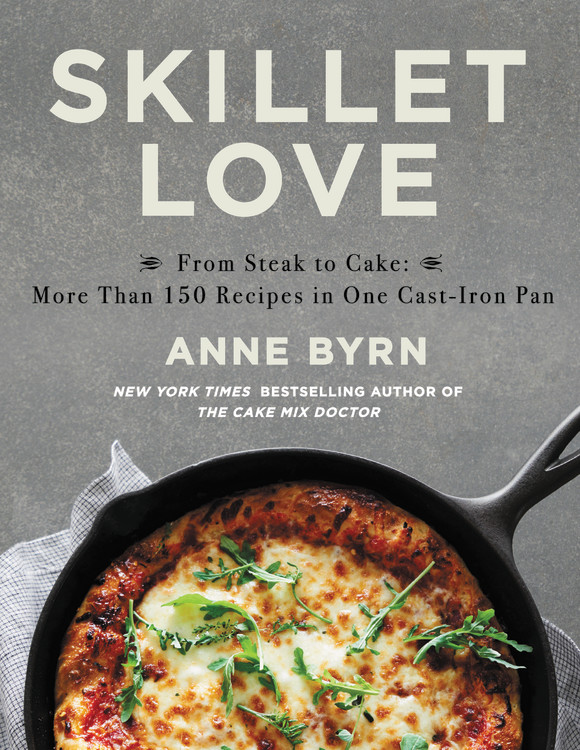

Skillet Love

From Steak to Cake: More Than 150 Recipes in One Cast-Iron Pan

Contributors

By Anne Byrn

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538763186

Price

$32.00Price

$42.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $42.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A delicious celebration of the cast iron pan–by the mega-bestselling author of THE CAKE MIX DOCTOR.

Beloved by home cooks and professionals alike, the cast iron skillet is one of the most versatile pieces of equipment in your kitchen arsenal. Perfect for every meal of the day, the cast iron pan can be used to cook eggs, sear meat, roast whole dinners, and serve up dessert warm from the oven.

Bestselling author Anne Byrn has carefully curated 160 recipes to be made in one simple 12-inch cast iron skillet. These are dishes everyone can enjoy, from appetizers and breads like Easy Garlic Skillet knots to side dishes like Last-Minute Scalloped Potatoes, from brunch favorites to one-pot suppers like Skillet Eggplant Parmesan. And of course, no Anne Byrn cookbook would be complete without her innovative cakes like Georgia Burnt Caramel Cake, cookies like Brown Sugar Skillet Blondies, and pies and other delicious treats.

Scattered throughout are fun tidbits about the origin of the cast iron skillet and how to properly season and care for them. Anne Byrn has crafted an informational, adaptable, and deliciously indispensable guide to skillet recipes the whole family is sure to love.

Beloved by home cooks and professionals alike, the cast iron skillet is one of the most versatile pieces of equipment in your kitchen arsenal. Perfect for every meal of the day, the cast iron pan can be used to cook eggs, sear meat, roast whole dinners, and serve up dessert warm from the oven.

Bestselling author Anne Byrn has carefully curated 160 recipes to be made in one simple 12-inch cast iron skillet. These are dishes everyone can enjoy, from appetizers and breads like Easy Garlic Skillet knots to side dishes like Last-Minute Scalloped Potatoes, from brunch favorites to one-pot suppers like Skillet Eggplant Parmesan. And of course, no Anne Byrn cookbook would be complete without her innovative cakes like Georgia Burnt Caramel Cake, cookies like Brown Sugar Skillet Blondies, and pies and other delicious treats.

Scattered throughout are fun tidbits about the origin of the cast iron skillet and how to properly season and care for them. Anne Byrn has crafted an informational, adaptable, and deliciously indispensable guide to skillet recipes the whole family is sure to love.

Genre:

-

"Byrn (The Cake Mix Doctor) salutes the cast-iron skillet in this eye-opening and tasty collection. Calling it "the only pan you'll ever need," Byrn offers instructions for using it to sear, caramelize, roast, and bake. She presents a top-notch variety of recipes for small plates, salads, and vegetables, such as potato-onion latkes with cucumber raita; peppers stuffed with quinoa, raisins, green olives, and zucchini; and pan-roasted beets with spinach, cherries, and candied pecans . . . Where Byrn really shines is in her chapters on desserts and breads, biscuits, and buns, where she showcases appealing items not traditionally made in a skillet: pound cake, a cranberry and almond tart, Irish soda bread with drunk raisins, and skillet Yorkshire pudding. For those looking to learn about cast-iron skillet cooking, Byrn is an astute teacher, and this collection showcases new and appealing ways to create delicious meals using a kitchen mainstay."Publishers Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use