Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

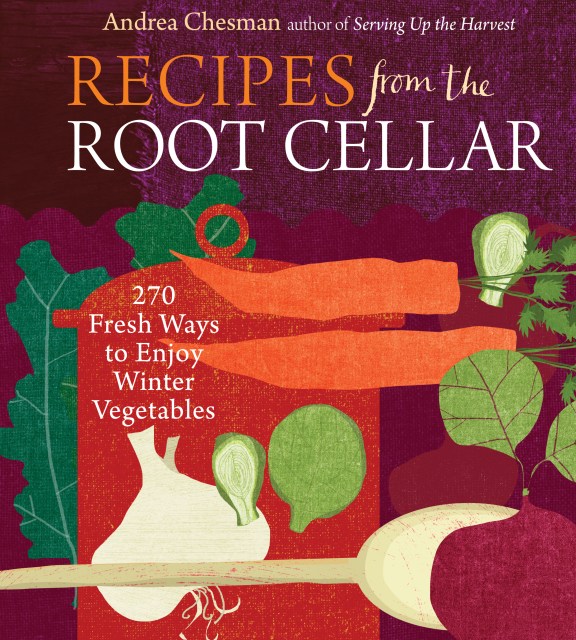

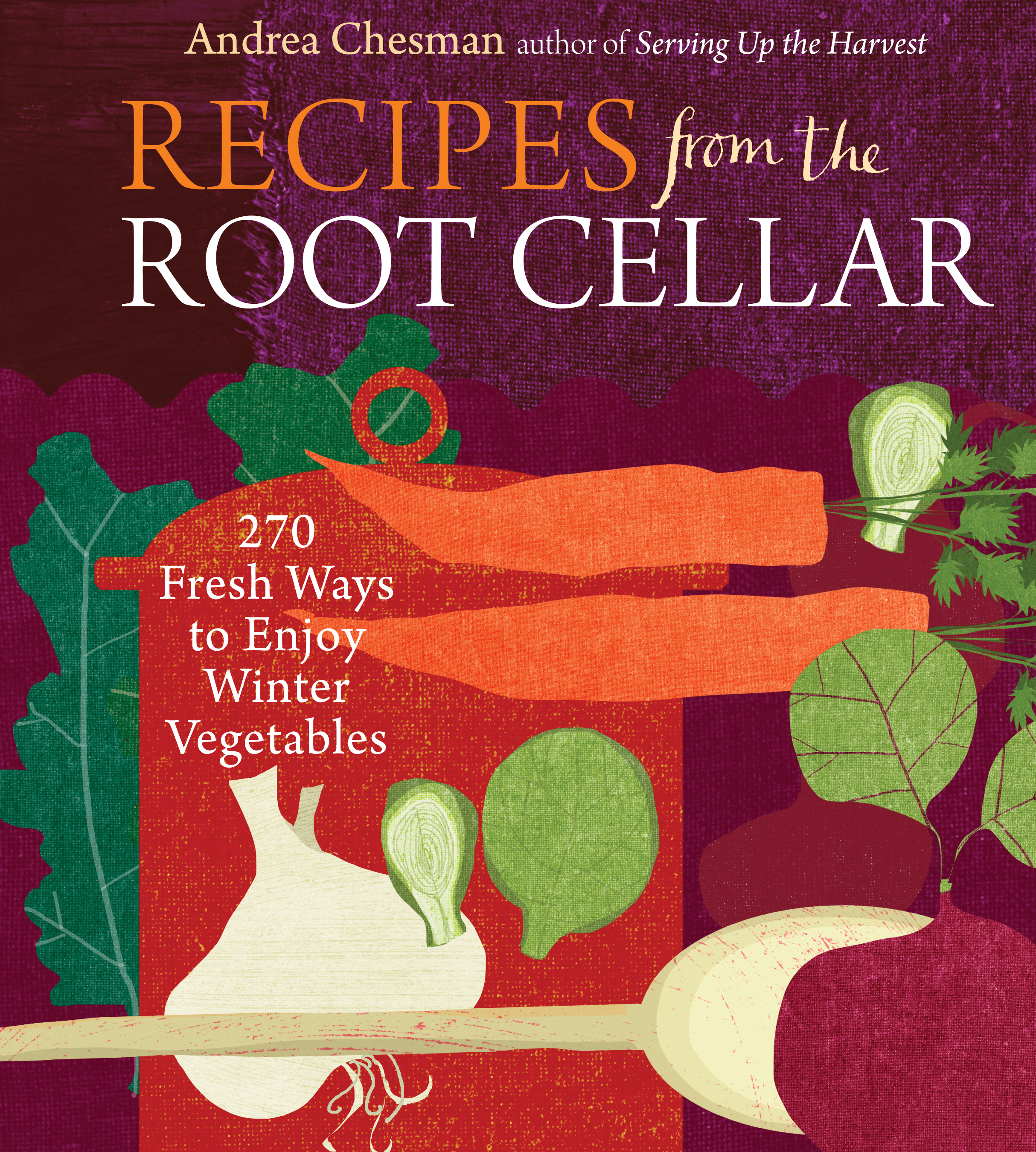

Recipes from the Root Cellar

270 Fresh Ways to Enjoy Winter Vegetables

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.95

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 24, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Sweet winter squashes, jewel-toned root vegetables, and hearty potatoes make local eating easy and delicious in the colder months of autumn and winter. Whether these vegetables are gathered straight from the garden, from a well-tended root cellar, or the market, their delectable flavors and nutritional benefits pack a powerful punch. With more than 250 easy-to-follow recipes that include Celery Root Bisque, White Lasagna with Winter Squash, and Thai Cabbage Salad, this collection will inspire you to explore the deliciously versatile world of root-cellar vegetables.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 24, 2010

- Page Count

- 387 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9781603423731

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use