Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

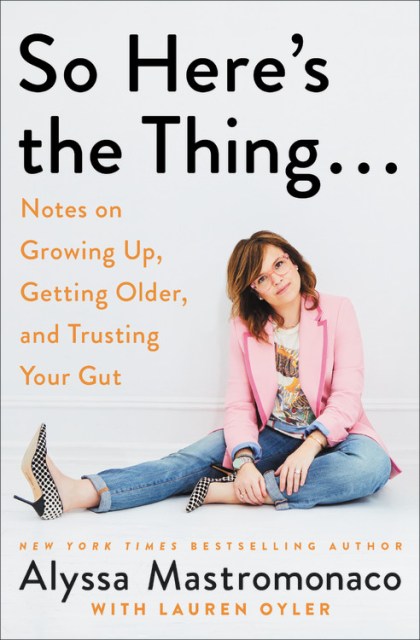

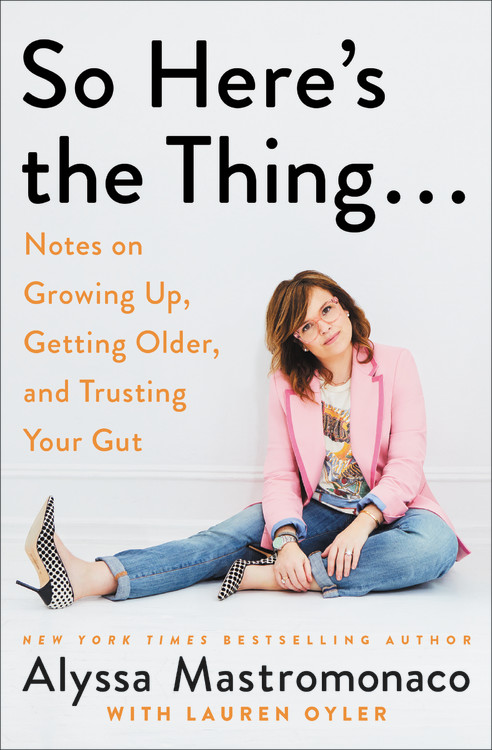

So Here's the Thing . . .

Notes on Growing Up, Getting Older, and Trusting Your Gut

Contributors

With Lauren Oyler

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 10, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From the New York Times bestselling author of Who Thought This Was a Good Idea? comes a fun, frank book of reflections, essays, and interviews on topics important to young women, ranging from politics and career to motherhood, sisterhood, and making and sustaining relationships of all kinds in the age of social media.

Alyssa Mastromonaco is back with a bold, no-nonsense, and no-holds-barred twenty-first-century girl’s guide to life, tackling the highs and lows of bodies, politics, relationships, moms, education, life on the internet, and pop culture. Whether discussing Barbra Streisand or The Bachelor, working in the West Wing or working on finding a wing woman, Alyssa leaves no stone unturned…and no awkward situation unexamined.

Like her bestseller Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?, SO HERE’S THE THING… brings a sharp eye and outsize sense of humor to the myriad issues facing women the world over, both in and out of the workplace. Along with Alyssa’s personal experiences and hard-won life lessons, interviews with women like Monica Lewinsky, Susan Rice, and Chelsea Handler round out this modern woman’s guide to, well, just about everything you can think of.

- On Sale

- Mar 10, 2020

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538731567

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use