Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

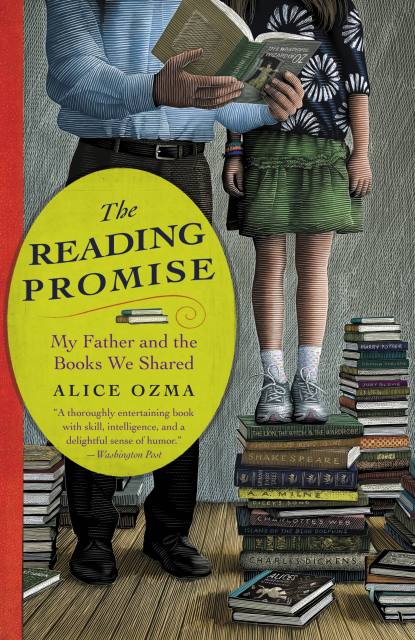

The Reading Promise

My Father and the Books We Shared

Contributors

By Alice Ozma

Foreword by Jim Brozina

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Alice Ozma was in 4th grade, she and her father decided to see if he could read aloud to her for 100 consecutive nights. On the hundreth night, they shared pancakes to celebrate, but it soon became evident that neither wanted to let go of their storytelling ritual. So they decided to continue what they called “The Streak.” Alice’s father read aloud to her every night without fail until the day she left for college.

Alice approaches her book as a series of vignettes about her relationship with her father and the life lessons learned from the books he read to her.

Books included in the Streak were: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, the Oz books by L. Frank Baum, Harry Potter by J. K. Rowling, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, and Shakespeare’s plays.

Alice approaches her book as a series of vignettes about her relationship with her father and the life lessons learned from the books he read to her.

Books included in the Streak were: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, the Oz books by L. Frank Baum, Harry Potter by J. K. Rowling, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, and Shakespeare’s plays.

Genre:

-

"Persuasive and influential, poignant and inspirational, Ozma's exuberant paean to the joys and rewards of reading-- and being read to-- is a must-read treasure for parents, especially, and bibliophiles, certainly." -Booklist, starred review

-

"This is the perfect book to hand any curmudgeon who needs reminding that reading makes a difference or thinks that today's youth are all blase. Highly recommended." -Library Journal, starred review

-

"Ozma's work is humorous, generous, and warmly felt, and with a terrific reading list included, there is no better argument for the benefits of reading to a child than this rich, imaginative work." -Publisher's Weekly

-

"A warm memoir and a gentle nudge to parents about the importance of books, quality time and reading to children." -Kirkus Reviews

-

"Alice Ozma has given us the gift of a remarkable love story. In her love of books, and of her father, we see the most-meaningful promises we might make to our own parents, our own children, and to ourselves." -Jeffrey Zaslow, coauthor, The Last Lecture

-

"Tender, funny, and deeply readable, THE READING PROMISE tells the story of how a simple ritual became a treasured father-daughter tradition. Promise yourself to revisit what matters...promise you'll pick up this tribute to the ways in which books change lives." - Erin Blakemore, author of The Heroine's Bookshelf

-

This is about so much more than books and reading. It's about single-parenthood and childhood, about raising a loving, witty, articulate kid, and all of it accomplished without anyone turning into the Alpha-Parent/Tiger-Dad. -Jim Trelease, author of The Read-Aloud Handbook

-

"THE READING PROMISE is a powerful testament to the difference a parent's devotion and the act of reading can make in a child's life. A rare and triumphant story." - Chris Gardner, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Pursuit of Happyness

- On Sale

- May 3, 2011

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455504503

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use