Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

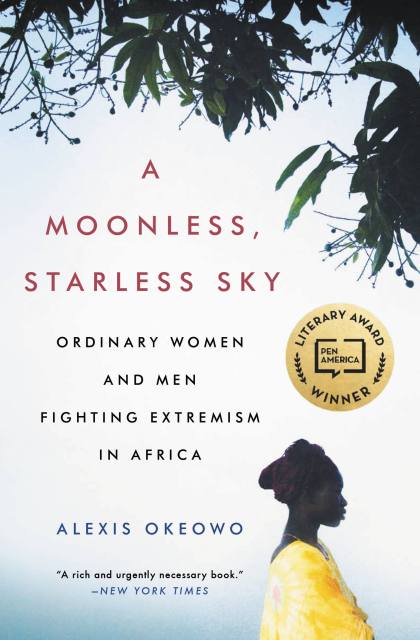

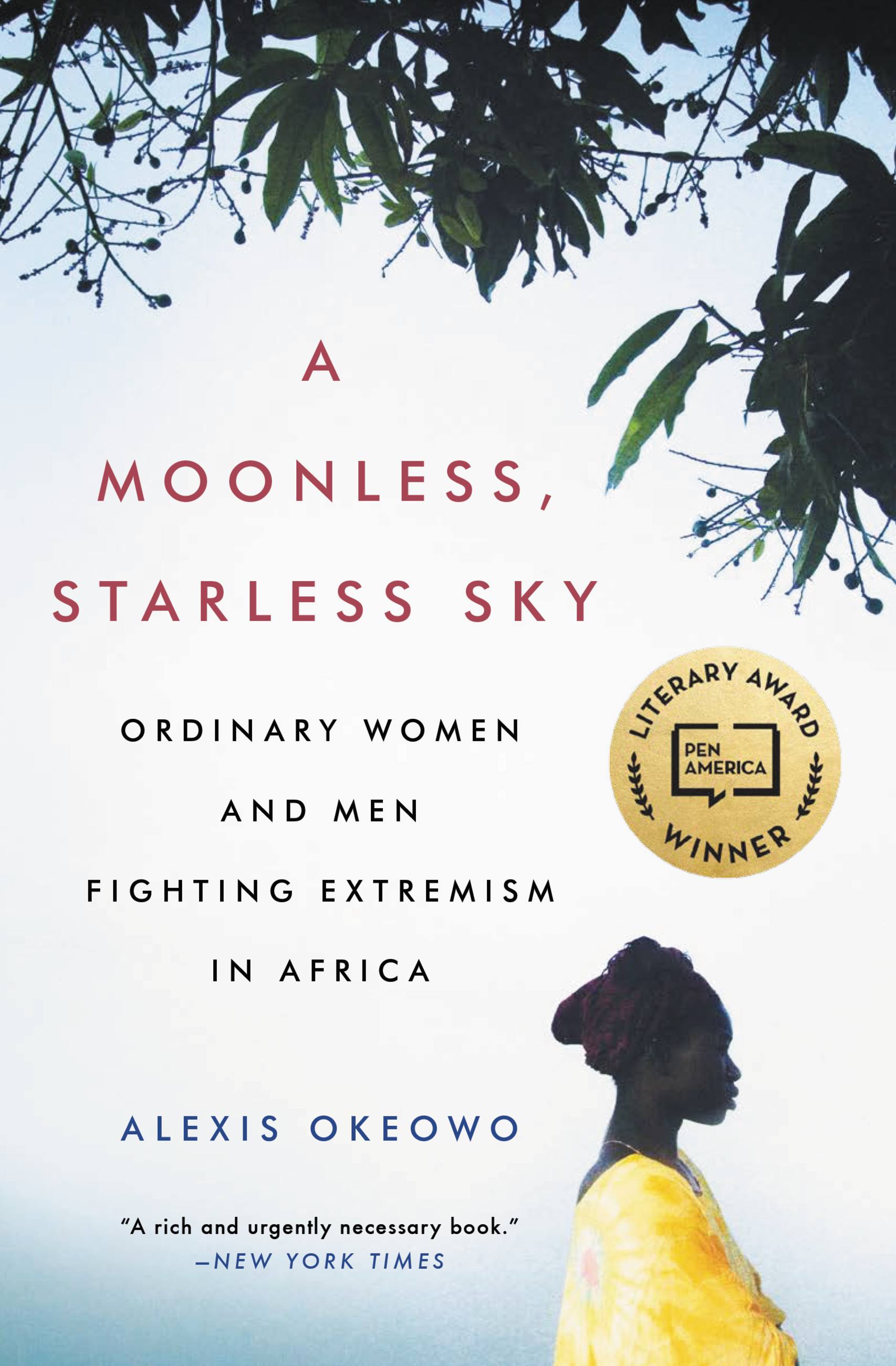

A Moonless, Starless Sky

Ordinary Women and Men Fighting Extremism in Africa

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.00 $34.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“A rich and urgently necessary book” (New York Times Book Review), A Moonless, Starless Sky is a masterful, humane work of journalism by Alexis Okeowo–a vivid narrative of Africans who are courageously resisting their continent’s wave of fundamentalism.

In A Moonless, Starless Sky Okeowo weaves together four narratives that form a powerful tapestry of modern Africa: a young couple, kidnap victims of Joseph Kony’s LRA; a Mauritanian waging a lonely campaign against modern-day slavery; a women’s basketball team flourishing amid war-torn Somalia; and a vigilante who takes up arms against the extremist group Boko Haram. This debut book by one of America’s most acclaimed young journalists illuminates the inner lives of ordinary people doing the extraordinary–lives that are too often hidden, underreported, or ignored by the rest of the world.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316382915

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use