Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

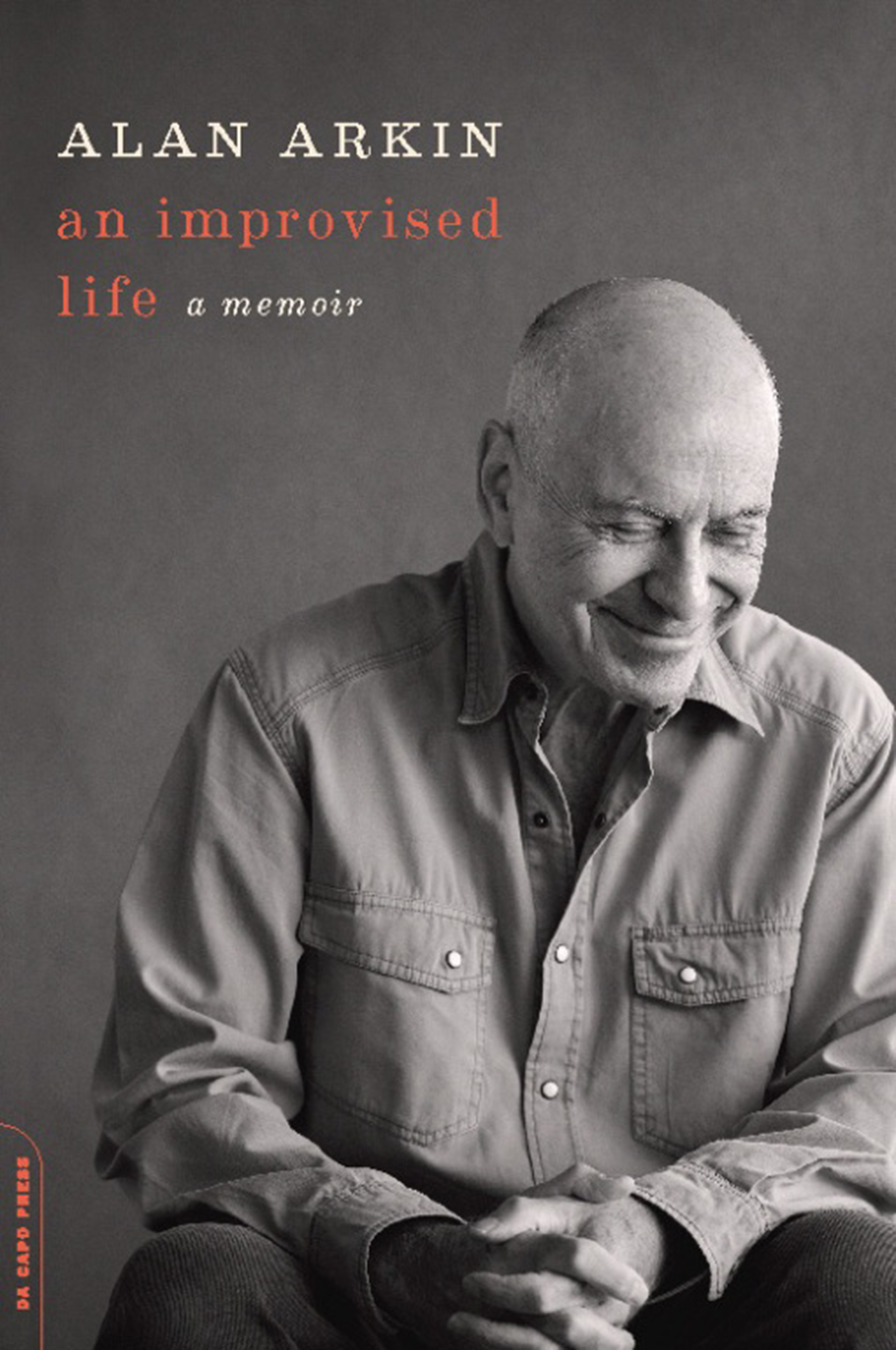

An Improvised Life

A Memoir

Contributors

By Alan Arkin

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 1, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In a manner that is direct, down-to-earth, accessible, and articulate, Academy Award-winner (Little Miss Sunshine, Argo, The Kominsky Method) Alan Arkin reveals insights not only about himself (and his audience and students), but also truths for the rest of us about work, relationships, and sense of self.

Alan Arkin knew he was going to be an actor from the age of five: "Every film I saw, every play, every piece of music fed an unquenchable need to turn myself into something other than what I was." An Improvised Life is the Oscar winner's wise and unpretentious recollection of the process–artistic and personal–of becoming an actor, and a revealing look into the creative mind of one of the best practitioners on stage or screen.

Alan Arkin knew he was going to be an actor from the age of five: "Every film I saw, every play, every piece of music fed an unquenchable need to turn myself into something other than what I was." An Improvised Life is the Oscar winner's wise and unpretentious recollection of the process–artistic and personal–of becoming an actor, and a revealing look into the creative mind of one of the best practitioners on stage or screen.

Genre:

-

“Who would've thought one of the best books of the year would be written by an actor?...For the aspiring actor, it provides inspiration as well as clear-eyed instruction, and for the cinephile, it provides insights into what makes actors stand out.”

ForeWord, July/August 2011

“Much like some of his personas on screen, Arkin is charming and warm in these personal recollections…The advice he offers can extend into anyone's life and help them to be more flexible and open to whatever changes might arise. To improvise, Arkin believes, is to grow closer to the self in an authentic way, and for him, that growth has led to a type of clarity and serenity that's inspiring.”

San Francisco Book Review, 7/25/11

“This intimate look into the life of Alan Arkin…is a creation well worth exploring. It not only brings the reader into Arkin's professional life, but shares glimpses into his personal life that will resonate with the reader.”

Albuquerque Journal

“More a musing on a life in acting than an autobiography…Arkin comes across as wry, sometimes brusque, but earnest almost to the point of nurturing. The book is less a celebrity memoir than a serious look at the principles of acting and improvisation that have driven his life.”

-

Los Angeles Times, “Jacket Copy” Blog, 4/1/11

“A charming little book that throws open the door to improvisational theater, inviting us all to engage in a little ‘make believe'…An unassuming, self-effacing book.”

WomanAroundTown.com, 3/29/11

“Alan Arkin brings as much truth to his autobiography as he does to his work as an actor.”

Reference and Research Book News, April 2011

“Arkin takes readers along on a journey through his career and the discoveries he made about acting and life along the way.”

New York Post, 5/29/11

“It's hard to read [Arkin's] memoir without hearing his voice—gruff, semi-sarcastic but wise—in every sentence.”

Times Literary Supplement (UK), 6/1/11

“[Arkin] employs his anecdotal discoveries with elegance and his observations are sharp and unrelenting…For the layman there is an unflinching glimpse into the creative process. For the professional it confirms the simplest of rules: stick to the basics—to the truth of the moment.”

Portland Book Review, June-August 2011 -

Bookgasm, 3/14/11

“[A] wise and unpretentious recollection of the process—artistic and personal—of becoming an actor, and a revealing look into the creative mind of one of the best practitioners on stage or screen. In a manner that is direct, down-to-earth, accessible and articulate, Arkin reveals insights not only about himself, but also truths for the rest of us about work, relationships and sense of self.”

Richard Crouse, noted Canadian film critic, 3/18/11

“Anyone who is an actor or who has ever thought of becoming an actor should read this candid, fascinating book.”

PopMatters.com, 3/21/11

“[Arkin] establishes himself fully as an intelligent man, serious but not pretentious, who writes with graceful honesty and a welcome economy. He has things to say—from both sides of the camera—about performance as a vehicle for emotional reality, and its attendant effects on the performer's psyche, that even the casual film fan can recognize as valid.”

-

Bookviews.com, March 2011

“Arkin, unlike many actors, has an intellect that takes in more than just acting.”

Albuquerque Journal

“Stimulating, thoughtful and instructive. Readers familiar with Arkin from his recent, rather brusque comedic roles may be somewhat surprised by the earnest, introspective, circumspect character on these pages, but the warmth of the real man emerges in his intimate sharing of something he so obviously and deeply treasures—his life's work.”

Local IQ (Albuquerque)

“An uncommonly well written and thoughtful memoir by an actor with a career that speaks for itself.”

A.V. Club, The Onion, 3/10/11

“For anyone curious about the thought processes of one of America's finest working character actors, it's worth a breezy look.”

New York Journal of Books, 3/1/11

“[Arkin] communicates his philosophy and principles of acting articulately and clearly. His easy-going prose is entertaining to any reader, but to those with a deeper interest in theater, the book contains valuable gems.”

-

Kirkus Reviews, 1/1/10

“Arkin's approach to autobiography is a bit unexpected—the intensely earnest, verging-on-New-Age tone is distinctly at odds with his familiar brusque, comedic persona—but rewarding, as the author illustrates the principles of his acting philosophy with a wealth of concrete details taken directly from his experience, resulting in a coherent and provocative manifesto…He also displays a refreshing lack of egocentrism…Earnest, intelligent and well-observed—less a celebrity memoir than a serious consideration of the principles of acting and improvisation.”

Publishers Weekly, 1/10/11

“More a reflection on acting than a straightforward memoir, Academy Award-winner Arkin's musing on the creative process is a welcome window into the mind of an artist…[An] engaging and instructive book.”

Library Journal (starred review), 2/15/11

“A profoundly honest and revelatory reckoning of an artistic and personal awakening…As honest and truthful a story of a life journey and arc toward artistic freedom as you are likely to find. All artists would benefit from Arkin's accrued insights and wisdom.”

Village Voice “La Daily Musto” blog, 2/23/11

“A great read—probing, educational, and wise.”

-

Blogcritics.org, 3/11/11

“Arkin tells his story simply, easily drawing the reader into his world. At only 191 pages, An Improvised Life is not a long book but there is a wealth of life experience in those pages. If you are at all interested in reading about the craft of acting from the point of view of one who values it above fame, you'll want to read Alan Arkin's An Improvised Life.”

Toronto Globe & Mail, 3/5/11

“A memoir of an acting life, full of inside details.”

Philadelphia Inquirer, FLICKgrrrl Blog, 3/8/11

“I'm charmed by [Arkin's] new memoir, An Improvised Life, and am delighted to report he has the same gravity and levity as a writer that he has as a performer…Read the book. Then treat yourself with an Arkin film.”

Washington Post, 3/13/11

“[An] uncompromising, thoughtful and surprising book.”

-

Huffington Post, 3/21/11

“[A] thoughtful look back at a long and distinguished career…Fans and admirers of the Academy Award-winning star will enjoy An Improvised Life for the insight to be gained from this personal visit with an actor who proves to be quite deft with a pen. Those who share Arkin's interest in the acting life will find a great deal to like here, as well.”

January, 3/21/11

“[A] thoughtful look back at a long and distinguished career…Fans and admirers of the Academy Award-winning star will enjoy An Improvised Life for the insight to be gained from this personal visit with an actor who proves to be quite deft with a pen. Those who share Arkin's interest in the acting life will find a great deal to like here, as well.”

Massachusetts Daily Collegian, 3/24/11

“This pleasure read does not require sitting with an encyclopedia or Google search open, simply an interest in the mind's workings of an icon in the arts.”

Kingman Daily Miner, 3/25/11

“A lot of food for thought…Highly recommended.”

Total Film, UK, May 2011

“A readable look at how the young New Yorker found his way to Chicago's Second City improv troupe and made the most of the opportunities it opened up for him.”

- On Sale

- Mar 1, 2011

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306819742

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use