Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

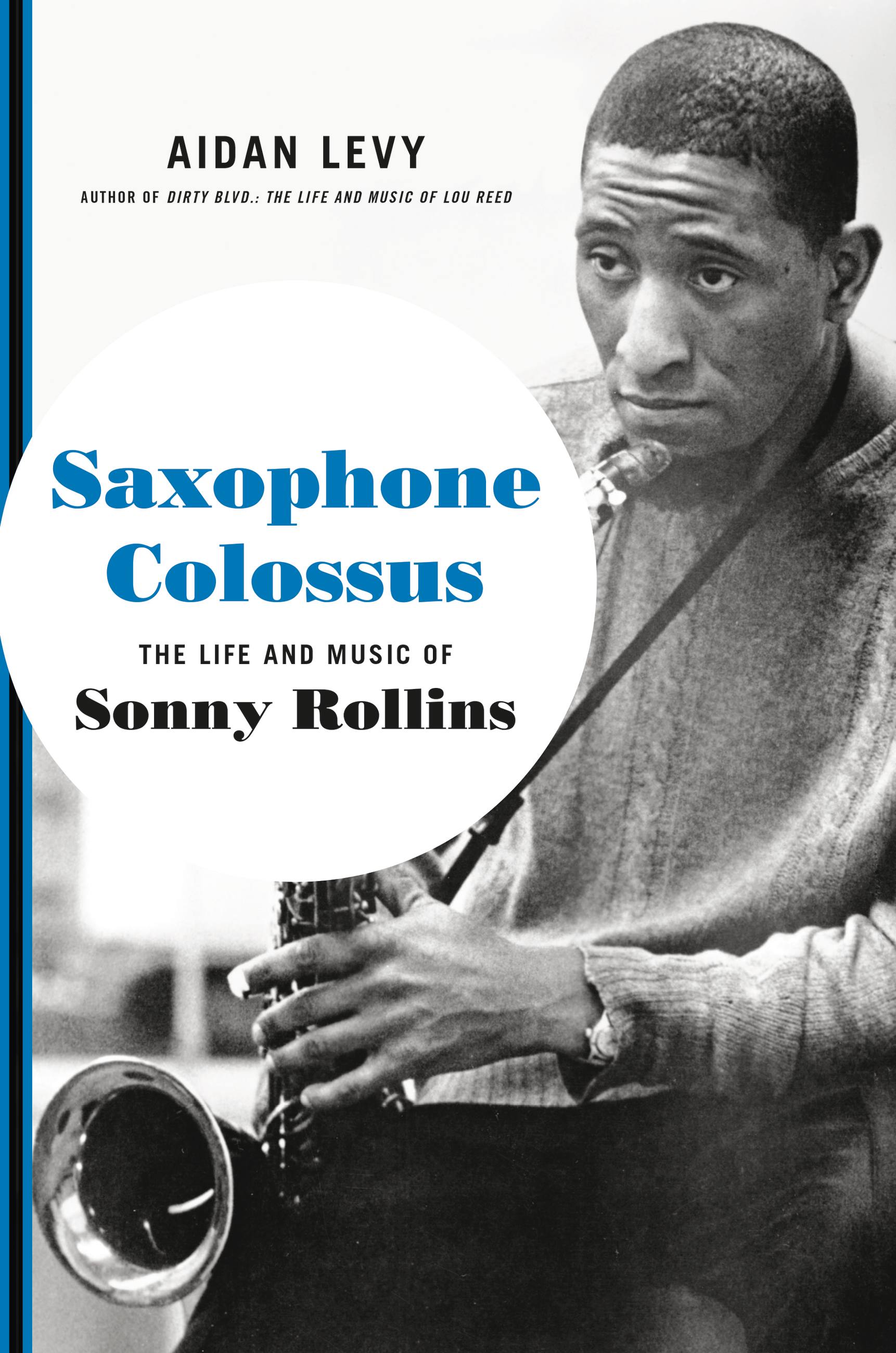

Saxophone Colossus

The Life and Music of Sonny Rollins

Contributors

By Aidan Levy

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 6, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

**Winner of the American Book Award (2023)**

**Longlisted for the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award (2023)**

The long-awaited first full biography of legendary jazz saxophonist and composer Sonny Rollins

Sonny Rollins has long been considered an enigma. Known as the “Saxophone Colossus,” he is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest jazz improvisers of all time, winning Grammys, the Austrian Cross of Honor, Sweden’s Polar Music Prize and a National Medal of Arts. A bridge from bebop to the avant-garde, he is a lasting link to the golden age of jazz, pictured in the iconic “Great Day in Harlem” portrait. His seven-decade career has been well documented, but the backstage life of the man once called “the only jazz recluse” has gone largely untold—until now.

Based on more than 200 interviews with Rollins himself, family members, friends, and collaborators, as well as Rollins’ extensive personal archive, Saxophone Colossus is the comprehensive portrait of this legendary saxophonist and composer, civil rights activist and environmentalist. A child of the Harlem Renaissance, Rollins’ precocious talent landed him on the bandstand and in the recording studio with Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie, or playing opposite Billie Holiday. An icon in his own right, he recorded Tenor Madness, featuring John Coltrane; Way Out West; Freedom Suite, the first civil rights-themed album of the hard bop era; A Night at the Village Vanguard; and the 1956 classic Saxophone Colossus.

Yet his meteoric rise to fame was not without its challenges. He served two sentences on Rikers Island and won his battle with heroin addiction. In 1959, Rollins took a two-year sabbatical from recording and performing, practicing up to 16 hours a day on the Williamsburg Bridge. In 1968, he left again to study at an ashram in India. He returned to performing from 1971 until his retirement in 2012.

The story of Sonny Rollins—innovative, unpredictable, larger than life—is the story of jazz itself, and Sonny’s own narrative is as timeless and timely as the art form he represents. Part jazz oral history told in the musicians’ own words, part chronicle of one man’s quest for social justice and spiritual enlightenment, this is the definitive biography of one of the most enduring and influential artists in jazz and American history.

Genre:

-

**Winner of the American Book Award (2023)**

**Longlisted for the PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award (2023)**

**Jazz Journalists Association's Jazz Awards, Biography/Autobiography of the Year (2022)**

Boston Globe, "Best Books of 2022"

WBGO, "Jazz Lovers' Gift Guide" -

“A revealing, comprehensive biography... [and] a brimming and organized compendium, something to keep returning to like Rollins’s records…”New York Times

-

“Levy paints a vivid picture…Throughout SAXOPHONE COLOSSUS he weds his extensive research to a feel for detail and narrative; the book is certainly long, but it has too much great reporting to be dry.”Los Angeles Times

-

"[Author Aidan Levy] distills essential truths... and ties strands of Mr. Rollins’s history together in poignant ways.”Wall Street Journal

-

“Aidan Levy’s indefatigable research and interviewing process has allowed him to fill SAXOPHONE COLOSSUS with a vast chorus of voices.”The Wire

-

"A figure of such heroic stature deserves a monument worthy of him. And until something even larger and more expansive comes along, Aidan Levy’s new biography of Rollins will do nicely… an admiring yet clear-eyed chronicle.”The Nation

-

“An incredibly deep, well-researched and thoughtfully written biography.”DownBeat

-

“[An] exhaustive, definitive biography.”Air Mail

-

“Read it you must....a remarkable read.”Marlbank

-

“There’s no doubt that SAXOPHONE COLOSSUS will be a great resource for future jazz scholars.”Nelson George Mixtape

-

“A long book allows for a luxurious detail....Saxophone Colossus does what the best biographies do: Gives you enough information to pursue your own lines of inquiry.”Point of Departure

-

"Monumental."WICN "Inquiry"

-

“A wonderful detailed and insightful journey through the life of an incredible artist and thinker. It is unlikely anyone will pen anything about Rollins, and maybe any other jazz musician, that will be its equal.”NYS Music

-

“A memorable work that will become the standard biography of the saxophone giant and should be embraced by all jazz fans and general readers. Highly recommended.”Library Journal

-

“[Saxophone Colossus is filled with]...precise and ravishing descriptions of Rollins’ music, ‘tireless work ethic,’ inspirations, frustrations with the record industry, social and environmental activism, and surprising collaborations.”Booklist

-

"[The] definitive account of a jazz icon."Kirkus

-

“Moving and meticulously researched.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Scrupulous and exhaustive... Levy comes as close to the enigma of Rollins as any biographer could.”Telegraph (UK)

-

“Rollins has never deviated from the obsessive nature of his calling. He’s found a like-minded biographer, who paints pictures with words as adeptly as Rollins did with his saxophone. Subject and author deserve each other.”iPaper (UK)

-

“Sonny Rollins told stories through his horn. His ‘telling,’ no matter how intricate or elaborate, was always pure, honest, and vulnerable, while the storyteller himself remained elusive and intangible. Until now. In Aidan Levy, Mr. Rollins has found his chronicler, an immensely talented writer whose lyricism, mastery, and dedication to truth matches that of his subject. The result is an opera, a calypso, a magnificent symphony that captures All of Him: Sonny, Newk, Theodore, Wally, Brung Biji, and the one and only Saxophone Colossus.”Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

-

"When I was a boy, I knew nothing of Sonny Rollins, the man, but his music set me free. Now, forty-some-odd years later, this book has gifted me a profound, almost revelatory, appreciation of all it took for our singularly Great American Improviser to exist, to persist, to survive, to thrive, to comprehend, to transcend, to create, to liberate, to be — at once the towering, omnipotent, immortal Colossus and the humble, gentle, questioning, questing human. Sonny Rollins has always been the master storyteller of the jazz idiom. What an illuminative joy it is to finally read the story of his own life so exhaustively and engagingly told."Joshua Redman, Grammy-nominated saxophonist, composer, and educator

-

“Sonny Rollins is the most acclaimed and celebrated jazz musician alive. His fearless creativity and willingness to test his limits are the stuff of leg- ends, as are his modesty, discipline and self-criticism. With deep research and meticulous documentation, Levy, with the aid of Rollins, gives us a revelatory and richer picture of the man and his era. A colossus of a book.”John Szwed, author of Space Is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra and So What: The Life of Miles Davis

-

“In this forensically researched biography of an American hero, the elusive Sonny Rollins stands revealed not only as the great Jazz Maker but a man of profundity and passions. By combining the story of his rise as a Saxophone Colossus with a picture of the Black artist in an age when social progress was not necessarily a given, Levy has produced a memorable book.”Val Wilmer, author of As Serious As Your Life: Black Music and the Free Jazz Revolution, 1957-1977

-

“The life and music of Sonny Rollins as chronicled by acclaimed author Aidan Levy is an insightful view into the daily struggles, achievements and spiritual journey of whom I like to refer to as the ‘Maestro di Maestri,’ Mr. Sonny Rollins. All I can say is:Joe Lovano, saxophonist, composer, producer, educator and Grammy winner

II: READ LISTEN LISTEN READ :II

You will be enlightened as I am.”

-

"Aidan Levy has provided the jazz world and beyond an important documentation of one of the greatest musicians of all time. Sonny Rollins spoke his own language through the saxophone--just check out his solo on 'Alfie'! And Saxophone Colossus provides for us in words a portal to deeper understanding of this legendary jazz giant!"Terri Lyne Carrington, Grammy-winning drummer, producer, and composer

-

“[The] authoritative book on Rollins . . . among the best-researched books ever devoted to jazz.”Lewis Porter, Grammy-nominated pianist, composer, educator, and author of John Coltrane: His Life and Music and Playback with Lewis Porter

- On Sale

- Dec 6, 2022

- Page Count

- 640 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306902826

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use