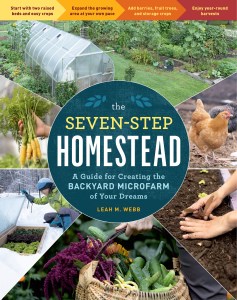

Seven Steps for Building a Backyard Microfarm

Motivated by the desire to provide her family with as much homegrown food as possible, Leah M. Webb developed this seven-step plan for creating a bountiful, food-producing backyard.

Today’s gardeners want a bit of everything—vegetables, fruit, medicinal herbs, flowers for pollinators, and even chickens for eggs. The dream is to create a diverse landscape that serves multiple functions, but approaching that goal can be overwhelming.

In The Seven-Step Homestead, garden consultant and expert homesteader Leah M. Webb shows gardeners of all levels that by starting small and adding more to their homestead every year, anyone can learn to grow more of their own food. Follow her seven steps for success.

Step 1: Starting Off Small: One or two Beds

I get it; you’re eager to fill your table and pantry with fresh fruits and vegetables harvested from your own garden. How hard can it possibly be? You see no reason to start small! Yet no one ever picks up a musical instrument for the first time and expects to play a complex melody. Why would we assume that gardening is any different? We first learn foundational skills, work to master the easy stuff, then expand when we’re ready.

Step 2: Four Hundred Square Feet

Now that you’ve mastered one or two small beds, you’re ready to expand your garden! Increasing your cultivation space to 400 square feet allows for greater production and opportunities to grow new plants. Increased diversity has a range of benefits that improve your garden’s productivity while supplying you with a greater abundance of food.

Step 3: Fruit Trees & Shrubs

Expanding your garden to incorporate perennial fruits offers endless possibilities. I’ve limited my discussion to common perennial fruits that grow in a wide range of climates, but many other fruits may be suitable for your region. Some of the more interesting selections may help you overcome challenges such as weather patterns, topography, soil conditions, and herbivore pressures. There’s much success to be had if you’re willing to combine a bit of experimentation with patience.

Step 4: Edible & Flowering Perennials

Expand your garden by 400 square feet to allow space for more edible and flowering perennials. Perennials return year after year, often with minimal effort, making them an important feature in a garden. You may choose to plant the entire expansion with perennials or to leave space throughout your new beds to plug in annuals.

Step 5: Four-Season Growing

In most climates, you can help cold-hardy vegetables thrive during winter by using a few simple tricks to extend the harvest season. You won’t need to preserve cold-hardy vegetables like kale, collards, leeks, beets, and lesser-known greens like chicory and cress when you can grow them year-round. Instead, you can focus your preservation efforts on fleeting summer foods like berries, fruits, tomatoes, tomatillos, squash, cucumbers, beans, and okra.

Step 6: Larger-Scale Storage Crops

Growing storage crops like dried beans, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and winter squash allows you to enjoy a garden’s bounty long after the fruits of summer have come and gone. Plants and seeds placed in late spring and early summer sprawl into remote corners of the garden. Generously allot space for these plants and be rewarded with unique and delightful storage crop varieties unavailable in most grocery stores.

Step 7: Farm-Fresh Eggs

Eggs from your own hens are packed with valuable proteins and fats, two of the macronutrients less easily found in food crops and important to human health. Chicken manure introduces a rich source of nutrition to garden soil. These diverse and important benefits of owning chickens are accompanied by a major commitment: Raising animals is demanding in that procrastination can equal neglect. Failing to sow seeds during an optimal window is excusable; allowing chickens to run out of water is not. If you’re up for the commitment, raising your own chickens is deeply rewarding as well as a source of ongoing entertainment!

Excerpted and adapted from The Seven-Step Homestead © by Leah M. Webb.

Today’s gardeners want a bit of everything—vegetables, fruit, medicinal herbs, flowers for pollinators, and even chickens for eggs. The dream is to build a diverse landscape that serves multiple functions, but achieving that goal can be intimidating and overwhelming. Homesteader Leah M. Webb shares her strategy for implementing a homestead plan in seven stages by starting small and gradually adding more features each year.

The Seven-Step Homestead takes readers through the process with a series of doable steps, beginning with establishing one or two raised beds of the easiest vegetables to grow, and gradually building up to the addition of fruit trees and berry bushes on hugelkulture mounds, a coop full of chickens, and a winter’s worth of storage crops. Step-by-step photos from the author’s own homestead, accompanied by her hard-earned advice and instruction, make this a one-of-a-kind guide for anyone who aspires to grow more of their own food.