PROLOGUE

Excerpt from THE BIG TIME by Michael MacCambridge

THE FANS CAME out in record numbers that night, from fervent true

believers to dedicated big-game collectors to curious dilettantes. It was one

of those peak occasions in American sports in which the gravity of the event

dominates the zeitgeist, momentarily transcending everything else going on

in the world. As with any long-awaited showdown, the most loyal advocates

on each side of the rivalry had gone a bit crazy with the waiting. They arrived

in all their brightly colored regalia, cheer buttons, t-shirts, and the inevitable

homemade signs. All the trappings were present: network television trucks

in the parking lot, a collegiate marching band striding the field in a bustling

pregame revelry, VIPs at every turn.

Though the event was absurd on its face—like so much else that happened

during the decade—it seemed urgent, necessary, and altogether logical

in the moment. On Thursday, September 20, 1973, in the midst of the

widespread misery of an oil crisis and a mounting Watergate investigation

that threatened Richard Nixon’s presidency, more than 45 million Americans

gathered around their TV sets to witness the most talked- about sports event

of the year.

It wasn’t a football game, or a boxing match, or the final of a major tournament.

It was a made-for-TV event, a reputed $100,000 “winner- take- all”

challenge match between the top-ranked women’s tennis player in the world,

the twenty-nine-year-old Billie Jean King, and the fifty-five-year-old former

Wimbledon men’s champion, Bobby Riggs. The crowd that night at the

Astrodome in Houston was the largest in history to attend a tennis match,

with a record American TV audience for the sport looking on.

Billed as the “Battle of the Sexes” or “the Libber vs. the Lobber,” it was

also a contest between two visions of what sports should be and, by extension,

two visions of what America should be. As both a sports event and a

cultural flashpoint, it was an occasion that would have been inconceivable

decade earlier or a decade later. Yet it was consistent with the sensibilities

and tone of the era, which is to say that the combatants were carried into the

arena by costumed handlers, like floats in a Mardi Gras parade. The tennis

hustler Riggs was transported to the court on a rickshaw, borne by a harem

of short- skirted beauties (“Bobby’s Bosom Buddies”), each wearing a gold

t-shirt with the Sugar Daddy candy bar logo, an early sign of the corporate

branding that would overrun sports in the coming decades. The defending

Wimbledon women’s champion King was brought to the court on a palanquin,

replete with a rooster-tail of faux-feathered plumage in the back, carried

by a group of bare-chested men posing as Roman soldiers, rumored to

be members of the Rice University swim team.

Riggs and King were perfect foils, diametrically opposed in all ways, from

their gender to their politics to their eyewear. Riggs, slight, flabby, slouching

into middle age, sporting the standard-issue, World War II–era black horn-rimmed

glasses, already a vestige of the past, a huckster who’d been playing

the con so well and for so long that he occasionally forgot it was a con. Then

King, at once strong and feminine, resplendent in a sequined multicolored

tennis dress (in menthol green and sky blue, created by the tennis devotee/

designer Ted Tinling), sporting blue suede tennis shoes, peering out from

behind au courant oval wire- rimmed glasses—compact, focused, and deceptively

strong.

The event came in the midst of a galvanizing era for women in America.

A year earlier, the first issue of Ms. magazine hit the newsstands, and

the New York congresswoman Shirley Chisholm became the first female to

seek a major-party nomination for the presidency. In the summer of 1972,

Congress passed the Education Amendments Act, containing Title IX, which

promised equality of opportunity for women in high school and college education.

Early in 1973, Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment and the

Supreme Court rendered its landmark decision on Roe v. Wade, protecting a

woman’s legal right to abortion.

The resistance to these shifts within the culture was swift and severe. No

one better symbolized the backlash than the aging self-proclaimed “male chauvinist

pig” Riggs, who’d trounced the previously top-ranked woman Margaret

Court earlier that year in “The Mother’s Day Massacre.” the twice-divorced

Riggs presented himself as a proud troglodyte on gender issues, and at

the heart of his persona was a contempt not merely for female athletes but

females as a whole. “Women don’t have the emotional stability to play,” he

proclaimed. “They belong in the bedroom and kitchen, in that order.” Riggs’

acolytes were in attendance that night, many sporting plastic pig snouts in

support. One of the night’s homemade signs read, “BILLIE JEAN WEARS

JOCKEY SHORTS.”

By the time they took the court, Riggs vs. King had evolved from a sports

event into a cultural proxy war. Las Vegas placed Riggs as the 8–5 favorite;

as was his custom, the hustler Riggs was betting on himself with assorted

media members. Many within women’s tennis, including King’s young rival

Chris Evert, expected a repeat of Riggs’ rout of Court. Others sensed that

King was made of sterner stuff, less easily daunted than Court, and more

cognizant of all that was at stake.

ABC’s live telecast, the first time a full tennis match had ever appeared

on prime-time network television in America, treated the event like a heavyweight

title fight, with Howard Cosell decked out in a tuxedo and courtside

seats going for $100.

During the National Anthem, Riggs was restless while King looked pensive

and determined. She’d been training like a boxer in the weeks leading

up to the bout, secluding herself, working on the problematic lobs that Riggs

loved to put up, which would be all the more difficult under the white ceiling

and glaring lights inside the Astrodome.

Over the previous months, she had done the requisite publicity to

build interest in the match, and had found herself swept up in the combative

vortex of the event, sufficient to understand that beyond trying to

beat Riggs, she also carried the pressure of the women’s movement on her

shoulders. She had won ten Grand Slam singles titles, helped launch the

Virginia Slims tour and was in the process of creating the novel concept

of World Team Tennis, to debut the following spring. Yet she realized—

correctly— that her legacy would be largely de#ned by the confrontation on

the court that night.

Then, in the tense, airless space right before the start of the match, came

the moment of clarity. Riggs had stubbornly insisted on wearing his training

jacket—it also had the corporate logo for Sugar Daddy—for the warm-up

session. Now, as they rested after their warm-up, King glanced over and

noticed her voluble opponent was sweating profusely and hyperventilating.

Somehow, with the whole world watching, and the perception of the women’s liberation movement in the balance, the man was even more nervous than the woman.

In that instant, Billie Jean King knew. It had been all circus and bombast

in the months leading up to the match, and pure spectacle on the night, but

now it was an athletic event, a match like any other. She was younger, fitter,

smarter, more prepared. She understood, even as she was toweling off her

racket grip and adjusting her glasses, that she was going to win.

What she may not have fully understood in that moment is that the women’s

movement— and sports in America— would never be the same.

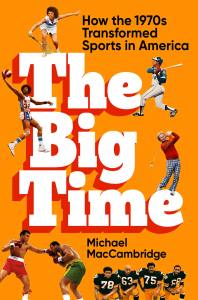

A captivating chronicle of the pivotal decade in American sports, when the games invaded prime time, and sports moved from the margins to the mainstream of American culture.

Every decade brings change, but as Michael MacCambridge chronicles in THE BIG TIME, no decade in American sports history featured such convulsive cultural shifts as the 1970s. So many things happened during the decade—the move of sports into prime-time television, the beginning of athletes’ gaining a sense of autonomy for their own careers, integration becoming—at least within sports—more of the rule than the exception, and the social revolution that brought females more decisively into sports, as athletes, coaches, executives, and spectators. More than politicians, musicians or actors, the decade in America was defined by its most exemplary athletes. The sweeping changes in the decade could be seen in the collective experience of Billie Jean King and Muhammad Ali, Henry Aaron and Julius Erving, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Joe Greene, Jack Nicklaus and Chris Evert, among others, who redefined the role of athletes and athletics in American culture. The Seventies witnessed the emergence of spectator sports as an ever-expanding mainstream phenomenon, as well as dramatic changes in the way athletes were paid, portrayed, and packaged. In tracing the epic narrative of how American sports was transformed in the Seventies, a larger story emerges: of how America itself changed, and how spectator sports moved decisively on a trajectory toward what it has become today, the last truly “big tent” in American culture.