The first Ali-Frazier fight, March 8, 1971…

Excerpt from THE BIG TIME by Michael MacCambridge

In the wake of the protracted debate, there was ample evidence in another

realm of the sports world that athletes deserved a bigger share of the vast

amount of money fans were paying.

The political scientist Andrew Hacker somewhat prematurely announced

1970 as “the end of the American era,” arguing that the United States was

no longer a nation, but instead a collection of “two hundred million egos.”

The grandest ego in the country may well have belonged to Muhammad Ali,

whose unignorable presence in the previous decade carried over into the

next.

Fully six years after converting to Islam, Ali remained a divisive figure,

facing the prospect of five years in a federal prison for refusing induction into

the military. The case was still on appeal in 1970 when promoters found a

way around the strictures that most state boxing commissions placed against

licensing. Ali would return to the ring for an October 26 fight against Jerry

Quarry in Atlanta, Ali’s first bout since the spring of 1967.

Ali’s comeback featured a landmark moment in American history, the

mainstream acknowledgment of Atlanta as a fount of Black culture. “From

every corner of the country and world they came,” wrote Mark Kram in Sports

Illustrated, “in brilliant plumage, the most startling assembly of black power

and black money ever displayed.”

Ali’s entourage for the fight was tour bus–sized, and left from an Atlanta

hotel. (Coretta Scott King, slated to ride on the bus, was running late and was

left behind.) Sidney Poitier stopped by Ali’s dressing room in the minutes

before the fight.

Waiting for Ali in the ring was the latest, not-so-great white hope, the

brawny Jerry Quarry from California. !en to raucous applause, stepping

through the ropes in white satin trunks with black trim, appearing like an

apparition, 1,314 days after his last fight, there at last was Ali.

That night also marked the return of the man who served an essential

but ineffable role in the Ali universe, Drew “Bundini” Brown, the confidant,

consigliere, and cheerleader for which there had never really been an analog

in the history of professional sports; Ben Hogan never had a hype man.

Ali showed rust in the return bout but retained the core of his remarkable

skills. Bundini, from the #rst round on, resumed regularly scheduled programming

after the three-eand-a-half-eyear interruption, shouting, “We here

all night!” every time Ali tagged Quarry with a left jab in the first round,

which was often. The fight ended by the fourth round, with Quarry’s face

reduced to a bloody mess.

There was one more tune-up, against the awkward, difficult Argentine

Oscar Bonavena, who accused Ali of cowardice (“You chicken . . . you no go in

Army”) at the weigh-in, and lasted into the fifteenth round before Ali scored

a TKO. At ringside, the heavyweight champion Joe Frazier described the

fight as “the dullest I ever saw.”

By that time, Frazier and Ali were already inextricably linked, two fighters

on a collision course that spoke to the anguished, conflicted moment in

American history.

Joe Frazier often had the expression of a man just realizing that something

important in his life wasn’t quite working out. !e 1964 Olympic heavyweight

champion was easily stereotyped—by both the media and by Ali—but had

already surmounted a series of forbidding obstacles and emerged his own

man. His father, a sharecropper in South Carolina, lost an arm in a farming

accident. Joe toiled on the farm before eventually taking a Greyhound bus up

north, settling in Philadelphia, where he began his amateur boxing career.

After winning the gold in Tokyo, he turned pro and worked his way up the

rankings. In Ali’s absence, Jimmy Ellis had won a tournament sponsored by

the World Boxing Association to fill the vacated heavyweight championship.

Frazier, who’d declined to compete in the tournament to protest the WBA’s

decision to strip Ali of his title, defeated Ellis in four rounds to assume the

title in February 1970.

Frazier understood better than anyone that he needed to beat Ali to be

considered a true champion. The two men had been circling each other for

years, wary but friendly while preparing for a confrontation that they both

wanted.

While Frazier was often depicted as a rural country bumpkin, he in fact

had his own measure of flamboyance; he was seriously intent on pursuing a

singing career, and routinely sported a pinky ring with a three-and-a-half carat

diamond. As the Ali fight neared, Frazier even ventured toward a

design innovation. Discussing a new boxing robe with a seamstress in 1970,

Frazier ordered, “Make me a good one this time. I want it green because

that’s my color and I’m going to stick with it, and I want gold flecks on it.

What’s flecks? You know how Liberace has his jackets made? That’s flecks.”

By the end of the year, the stage was set for the first-ever confrontation

between two undefeated heavyweight champions—“The Fight of the

Century”— between Ali and Frazier on March 8, 1971, in Madison Square

Garden.

The appeal of the fight was obvious. So, too, was the degree to which the

promise of Ali–Frazier transcended sports. Here was the boastful, draft-

dodging Black Muslim Ali representing much of the new stridency of modern

American culture. He was matched against the sullen but respectful

Frazier, a man of more conventional bent. Whom you were rooting for often

said something about the sort of person you were.

The top bid for the bout was an unthinkable $2.5 million guaranteed to

each boxer from a consortium led by the longtime MCA agent and entrepreneur

Jerry Perenchio and the Los Angeles Lakers’ owner Jack Kent Cooke. “I

knew right away I wanted it,” Perenchio said. “This was the sort of thing I’d

been training twenty years for.”

Perenchio had lived a riches-to-rags adolescence. The son of A. J. Perenchio,

co-owner of Sunnyside Winery, he went to private schools, only to see

his father go broke once the son started at UCLA. So the younger Perenchio

hustled, booking bands for frat parties and dances up and down the West

Coast, later rising through MCA as an agent and protégé of chairman Lew

Wasserman. He opened his own talent agency, Chartwell Artists, whose clients

included Glen Campbell, Henry Mancini and Andy Williams. In 1968,

he bought the Chartwell Estate that had been used as the location for the

1960s sitcom !e Beverly Hillbillies.

“This one transcends boxing,” promised Perenchio in the buildup. “It’s a

show business spectacular. You’ve got to throw away the book on this fight.

It’s potentially the greatest grosser in the history of the world.”

With a keen eye to the deal, he and Cooke recognized that a big guarantee

would likely earn the trust of Ali and Frazier, and also give the promoters

more latitude to keep the pro#t from the closed- circuit broadcast rights.

“Once Jerry put $2.5 million out there for each #ghter, it was closed,” said

the boxing promoter Bob Arum. “That blew everyone’s mind. No fighter had

ever made anything like that in the history of boxing, not Jack Dempsey, not

Gene Tunney, not Louis, nobody!”

In fact, nobody in the history of sports had made that kind of money.

Ali–Frazier was an event that hinted at the riches sports could bring. The

cultural resonance was what made the fight so wildly discussed, but it was

the purse that landed the two boxers on the cover of Time magazine, under

the headline, “The $5,000,000 Fighters.”

With Perenchio’s direction, the event was billed like a major movie

premiere— “THE FIGHT” read the billing on the match program, with profile

shots of Ali and Frazier beneath a shot of Madison Square Garden’s glimmering

ceiling.

It was the kind of #ght for which the writer George Plimpton would throw

a pre- bout party at Elaine’s, attended by Norman Mailer, Pete Hamill, Bruce

Jay Friedman and dozens of other luminaries from the world of literature

and the arts.

While Ali was still an undeniably polarizing #gure, his constituency had

grown considerably since he was stripped of his title. College students, white

intellectuals, anti-war protesters— an odd alliance of acolytes— had rallied to

his cause. It helped that the Vietnam War was far less popular than it had

been in 1967, and a consensus was building that Ali’s anti- war stance was

sincere. But there was something more at work— a sense within much of the

culture that his declamations weren’t disrespectful so much as celebratory.

Ali hadn’t changed his message considerably; what was beginning to change

was America.

While Ali’s popularity in the Black community was a given, there was

complexity even to that. Growing up in Philadelphia, the writer Gerald Early

remembered identifying with Frazier even as he preferred Ali.

“If you want to look at it in a certain way, Ali represented the new black

person, and Frazier was the old Negro,” said Early. “So there it was. I had a

certain kind of sympathy with that, and Frazier reminded me of my uncles,

and the black men I grew up with in the neighborhood. I kind of knew people

like Joe Frazier. I had never known anybody like Muhammad Ali.”

On the eve of the fight, visited by writers to his hotel suite at the New

Yorker, Ali doubled down on his framing of Frazier as an Uncle Tom and

the white man’s choice. “Frazier’s no real champion,” Ali charged. “Nobody

wants to talk to him. Oh, maybe Nixon. Nixon will call him if he wins. I

don’t think he’ll call me.”

On the night of March 8, 1971, people flocked by the tens of thousands

to halls and arenas, auditoriums and stadiums, to watch the closed-circuit

broadcast. In Memphis, a sold-out crowd at Ellis Auditorium was packed,

and included the Ali supporter Elvis Presley, decked out in a $10,000 gold

belt for the occasion.

And at Madison Square Garden on the night was . . . well, everybody. “Stars

of stage and screen” doesn’t really begin to do it justice. Frank Sinatra was at

ringside, shooting photographs for Life magazine. Burt Lancaster was doing

color commentary for the closed-circuit broadcast. Miles Davis sat close to

the ring. The French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo accompanied the Italian

actress Antonella Lualdi. Isaac Hayes was there, as was Duke Ellington. Joe

Namath attended. Sammy Davis Jr. was there, as were Jack Nicholson, Robert

Redford and Barbra Streisand. So was Diana Ross, sporting black hot pants.

The Bruins’ Bobby Orr, longtime Ali fan, was close to ringside. So were Bob

Dylan and Diane Keaton. The Knicks had the night off, so Walt “Clyde” Frazier

was in attendance, as was the fanatical Knick follower Woody Allen.

Dustin Hoffman and Hugh Hefner were there, the latter with Barbi Benton,

who got more attention due to her see- through blouse.

Perhaps never before

had such a wide swath of American culture—high, low, Black, white, movies, music, sports—ever assembled for a single event.

If the fight was unprecedented, then so was the fashion. And it wasn’t

only the crowd that dressed up. For decades boxing matches paired fighters

in two of three different hues of trunks: white, black, or blue. But in this

instance, on this stage, in this decade, nothing so mundane would have sufficed.

So Ali arrived, for the first time in his career, in red trunks with white

trim, sporting red tassels on his white boxing boots. Frazier’s designer had

accommodated Smokin’ Joe’s request for “flecks,” and he sported trunks in a

jazzy print of green and gold.

The fight itself somehow lived up to the impossible hype, a perfect blend

of styles. Ali’s flowing movement, and his lightning jab from his superior

height and reach, meant he was always within striking distance. Frazier,

coiled but relentless, bobbed and weaved. Even though he was shorter and

slower than Ali, his deceptive, crablike movements made him a surprisingly

elusive target. Cutting off the ring from Ali, he burrowed into the previous

champ’s midsection, and from close quarters, fired off his dreaded left hook.

The battle ebbed back and forth. Ali could still move, but Frazier was

implacable. Absorbing punishment in the face from Ali’s jabs, he kept moving

in, punishing Ali with body blows and finally connecting with a fierce hook

that knocked Ali down in the fifteenth round. It was a startling moment, as

shocking to the crowd as it was to Ali himself.

The fight had been close, but Frazier’s stamina and the late knockdown

made the decision inevitable. In the commotion a”er the bell to end the fight,

as the fighters moved unsteadily to their respective corners, having survived

the draining spectacle, “Bundini” Brown was already in tears, in the forefront

of the Ali partisans who’d experienced the unthinkable, watching their

prince defiled.

The unanimous decision brought a sense of vengeful glee to the pro-Frazier

cohort in the crowd. Just a few feet away from the ring, the German actor

Curd Jürgens stood with his wife, the model Simone Bicheron, and, glaring

at Ali, said, “He deserved it. He deserved that beating.”

And at the White House that night, the inveterate sports fan Richard

Nixon, who’d arranged to have the closed-circuit broadcast screened at his

residence, celebrated Frazier’s decision over “that draft dodger asshole.”

In the aftermath of the fight, Frazier sat for the press with a face that was

a collage of bumps and bruises. He was at once proud of his accomplishment

and respectful of Ali. “Let me go and straighten out my face,” he said in concluding

his post-fight press conference. “I ain’t really quite this ugly.” Though

Frazier had won, the punishment he endured was enough to keep him hospitalized

for an extended stay.

“End of the Ali Legend,” blared one headline—but rumors of Ali’s demise

would prove premature. In the hours and days that followed, something

curious happened. Ali, the malcontent that white America wanted silenced,

became gracious, nearly gallant, in defeat. Like all the great champions

before him, he recognized the greatness of his opponent.

Ali’s case had been appealed all the way to the Supreme Court where, on

April 19, 1971, oral arguments were heard in the case of Cassius Marsellus Clay,

Jr. v. United States. (Ali had not legally changed his name when converting to

Islam in the ’60s.) On the morning of June 28, 1971, the decision came down,

with the court deciding in a unanimous opinion to overturn the conviction.

In this, too, the hyperkinetic Ali seemed atypically serene and at peace.

He cast no aspersions. “They only did what they thought was right,” he said.

“That was all. I can’t condemn them.”

Another reporter started to ask a question. “Champ—” he said, but Ali

cut him off.

“Don’t call me the champ,” he said quietly. “Joe’s the champ now.”

Somehow, Frazier, for so long hailed the white man’s hope to quiet the

loud Black Muslim, became smaller, not larger, in victory. !e call from the

president never did come that night. And the white America that had seemed

to embrace him beforehand suddenly cooled. Embarking on a concert tour of

the U.S. with his soul backing band the Knockouts, Frazier played in front of

fewer than 100 people at San Francisco’s Winterland.

Things did not improve during the European tour in the spring of 1971

that had been scheduled as a victory lap for Frazier, proof that he was every

bit the multi-talented hyphenate that the writer-debater-poet-actor Ali

wanted to be. But Frazier, who now had the rightful claim to be the undisputed

heavyweight champion of the world, didn’t have that ineffable appeal

that Ali would forever possess. !ere were more than 6,000 empty seats in

the 7,000-seat Pellikaan Hall near Amsterdam, and just 250 people buying

tickets in Cologne. Frazier sold just 28 tickets for a show in a 3,000-seat hall

in Copenhagen. Upon his return to the U.S., Frazier said, “Man, you can’t club

people over the head to make them come out.”

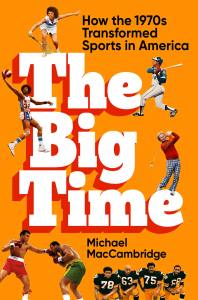

A captivating chronicle of the pivotal decade in American sports, when the games invaded prime time, and sports moved from the margins to the mainstream of American culture.

Every decade brings change, but as Michael MacCambridge chronicles in THE BIG TIME, no decade in American sports history featured such convulsive cultural shifts as the 1970s. So many things happened during the decade—the move of sports into prime-time television, the beginning of athletes’ gaining a sense of autonomy for their own careers, integration becoming—at least within sports—more of the rule than the exception, and the social revolution that brought females more decisively into sports, as athletes, coaches, executives, and spectators. More than politicians, musicians or actors, the decade in America was defined by its most exemplary athletes. The sweeping changes in the decade could be seen in the collective experience of Billie Jean King and Muhammad Ali, Henry Aaron and Julius Erving, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Joe Greene, Jack Nicklaus and Chris Evert, among others, who redefined the role of athletes and athletics in American culture. The Seventies witnessed the emergence of spectator sports as an ever-expanding mainstream phenomenon, as well as dramatic changes in the way athletes were paid, portrayed, and packaged. In tracing the epic narrative of how American sports was transformed in the Seventies, a larger story emerges: of how America itself changed, and how spectator sports moved decisively on a trajectory toward what it has become today, the last truly “big tent” in American culture.