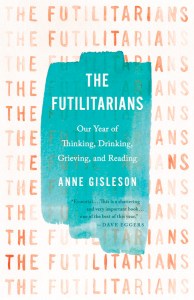

The Futilitarians: Q&A with author Anne Gisleson

What do you like most about writing?

The dedicated focus and the concentration. Life is busy, the world can be bonkers and my mind is often pretty messy and disorganized. The page is a designated space to try to straighten things out. Didion said it best: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.” It helps me know the world better. I love the scary luxury of sitting down to write and having no idea where it’s going to lead, what I’ll discover, how many times I’ll change my mind, etc. It’s a bonus if I actually get to share what I write with the world and have it connect with others.

What don’t you like about writing?

Once I accepted that the hundreds of thousands of unpublished words and dozens of failed pieces are all in service of the published, more successful ones, there’s not much I don’t like about writing. Except maybe the required self-involvement and prolonged detachment from loved ones.

Do you have a designated writing space?

Absolutely. I share a studio with my husband, who’s a visual artist. It’s big enough that we have our distinct spaces and we’re almost never there at the same time. It’s only about ten minutes away, but it’s outside of the city and you have to cross the Industrial Canal via a hundred year old drawbridge, and then cross the parish (county) line. So it feels as though you’re leaving your regular life and ritualistically entering a totally different zone. Since it’s the only thing I do in that space, it’s a productivity chamber. I walk in, make coffee, sit down, write, leave, and go to my other job or next thing.

What were your favorite books growing up/which books influenced your writing?

In some ways, I feel as though I’ve never gotten past the pull of Virginia Woolf’s work. I first read her in high school and it permanently imprinted on me. I’d read passages over and over and map out how far she could travel within a single sentence, the constant negotiation between the internal and external. Her ability to synthesize observation, emotion, imagination, and intellect so compactly always awed me. She made me pay attention to how we experience the world in any given moment, how it feels to be alive, and the difficulty of trying to write that.

How did Hurricane Katrina change New Orleans?

I think for every New Orleanian affected by Katrina the city changed in a different way. Civic life does feel more intentional, as we’ve had to confront a lot of issues that had languished over the years, and we’ve become more open to change and more visible nationally. Katrina brought in fresh waves of people and ideas, some helpful, some not as much. But, empirically, since the storm, the city is whiter, there’s less affordable housing and the beautifully rebuilt schools are more segregated. There was a big post-Katrina push to preserve the city’s celebrated culture but not necessarily the communities who create it and many long-time residents are being pushed out of their historic neighborhoods. All of this is very painful and, for me, clouds whatever gains the city has made. It’s also hard to separate out the city’s changes from the same urban trends happening all over the country — gentrification, the impact of short-term rentals. Katrina maybe accelerated those things here. On another note, not sure what the correlation is, but we do have the most exciting and robust literary scene I’ve experienced here in my lifetime.

How did Katrina change you as a writer?

It changed me vastly as a writer. Hurricane Katrina and motherhood hit me at the same time, in my thirties. The stakes were so suddenly so high and I could only think and write in these very urgent, life-or-death terms. I committed to nonfiction and to trying to relay the complexity of the city, of living in the aftermath. It was a fraught time for local writers because so much was riding on how the city was perceived by the rest of the country, and at the same time we were processing our own reactions to this crazy new reality. I remember bristling whenever anyone would be called “the voice of New Orleans” because there were so many different voices, and most not heard at all. Writing through all that destruction and anxiety, hope and work, obsession with the past and the future, I think some seal on my writing was broken and that sense of urgency has never gone away.

What kept you excited about writing The Futilitarians?

One of the most compelling aspects of writing it was the self-discovery. My father’s death and the group’s formation was such an astounding confluence. I knew a few months in that I wanted to write about it. Like the first year of grieving a loved one, the first year of any new effort like the Existential Crisis Reading Group, has its own intensity and momentum that can later fall away or mutate into something else. I wanted to capture that, but also realized it can sometimes take a while to sort things out and the process can be unpredictable. Through the writing itself and the feedback from others, I started to see stronger connections between my past (especially the deaths of my two sisters), the readings and the group’s project of philosophical exploration. Like the ECRG, the book feels like a conversation, like a collective endeavor.

Is the Existential Crisis Reading Group still going on?

Yes! It is. We still have a core group of a half dozen or so of the original members. Some original invitees decided after the first couple meetings that it wasn’t for them, and over the years, others have moved out of town. We occasionally invite new members or guests, but we try to keep it small and intimate. I really don’t know how the book’s release is going to play into the ongoing dynamic of the group, but people have been really supportive. It’s “meta” experience for them — reading about our reading group in a book. It’s a little weird, but also pretty cool, that some of our discussions have been launched from our living room out into the world.