By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

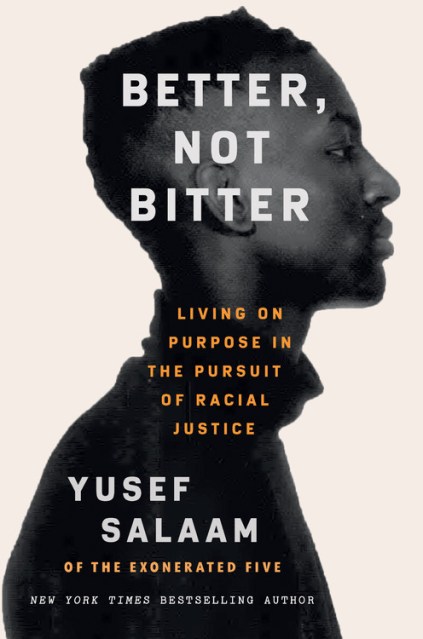

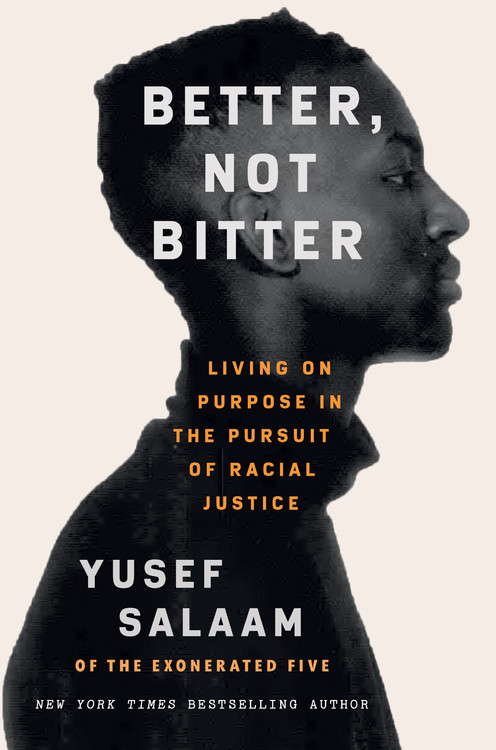

Better, Not Bitter

Living on Purpose in the Pursuit of Racial Justice

Contributors

By Yusef Salaam

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 18, 2021

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538705001

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 18, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Named a Best Book of 2021 by NPR

This inspirational memoir serves as a call to action from prison reform activist Yusef Salaam, of the Exonerated Five, that will inspire us all to turn our stories into tools for change in the pursuit of racial justice.

They didn’t know who they had.

So begins Yusef Salaam telling his story. No one’s life is the sum of the worst things that happened to them, and during Yusef Salaam’s seven years of wrongful incarceration as one of the Central Park Five, he grew from child to man, and gained a spiritual perspective on life. Yusef learned that we’re all “born on purpose, with a purpose.” Despite having confronted the racist heart of America while being “run over by the spiked wheels of injustice,” Yusef channeled his energy and pain into something positive, not just for himself but for other marginalized people and communities.

Better Not Bitter is the first time that one of the now Exonerated Five is telling his individual story, in his own words. Yusef writes his narrative: growing up Black in central Harlem in the ’80s, being raised by a strong, fierce mother and grandmother, his years of incarceration, his reentry, and exoneration. Yusef connects these stories to lessons and principles he learned that gave him the power to survive through the worst of life’s experiences. He inspires readers to accept their own path, to understand their own sense of purpose. With his intimate personal insights, Yusef unpacks the systems built and designed for profit and the oppression of Black and Brown people. He inspires readers to channel their fury into action, and through the spiritual, to turn that anger and trauma into a constructive force that lives alongside accountability and mobilizes change.

This memoir is an inspiring story that grew out of one of the gravest miscarriages of justice, one that not only speaks to a moment in time or the rage-filled present, but reflects a 400-year history of a nation’s inability to be held accountable for its sins. Yusef Salaam’s message is vital for our times, a motivating resource for enacting change. Better, Not Bitter has the power to soothe, inspire and transform. It is a galvanizing call to action.

This inspirational memoir serves as a call to action from prison reform activist Yusef Salaam, of the Exonerated Five, that will inspire us all to turn our stories into tools for change in the pursuit of racial justice.

They didn’t know who they had.

So begins Yusef Salaam telling his story. No one’s life is the sum of the worst things that happened to them, and during Yusef Salaam’s seven years of wrongful incarceration as one of the Central Park Five, he grew from child to man, and gained a spiritual perspective on life. Yusef learned that we’re all “born on purpose, with a purpose.” Despite having confronted the racist heart of America while being “run over by the spiked wheels of injustice,” Yusef channeled his energy and pain into something positive, not just for himself but for other marginalized people and communities.

Better Not Bitter is the first time that one of the now Exonerated Five is telling his individual story, in his own words. Yusef writes his narrative: growing up Black in central Harlem in the ’80s, being raised by a strong, fierce mother and grandmother, his years of incarceration, his reentry, and exoneration. Yusef connects these stories to lessons and principles he learned that gave him the power to survive through the worst of life’s experiences. He inspires readers to accept their own path, to understand their own sense of purpose. With his intimate personal insights, Yusef unpacks the systems built and designed for profit and the oppression of Black and Brown people. He inspires readers to channel their fury into action, and through the spiritual, to turn that anger and trauma into a constructive force that lives alongside accountability and mobilizes change.

This memoir is an inspiring story that grew out of one of the gravest miscarriages of justice, one that not only speaks to a moment in time or the rage-filled present, but reflects a 400-year history of a nation’s inability to be held accountable for its sins. Yusef Salaam’s message is vital for our times, a motivating resource for enacting change. Better, Not Bitter has the power to soothe, inspire and transform. It is a galvanizing call to action.

-

"Salaam's compelling memoir is one of astounding warmth…This book should be read by anyone who wants to hear the story of the Exonerated Five directly from one of its members.”NPR

-

"An important memoir and call to action that sheds light on the personal injustices of mass incarceration."Library Journal

-

“Warm, generous, and inspirational: a book for everyone.”Kirkus

-

“An uplifting and hopeful book.”Booklist

-

"Better Not Bitter is equal parts, a luminous journey of awakening, and an indictment of a system that swallows boys and girls whole, only to spit out their broken bones. It is an urgent and poetic treatise on the human spirit’s ability to make itself whole again over and over. I cried for the little boy who was imprisoned, and rejoiced for the man who emerged years later as a battle tested warrior for justice.”Shaka Senghor, New York Times bestselling author of Writing my Wrongs

-

"Punching the Air is the profound sound of humanity in verse... Utterly indispensable."Ibram X. Kendi, National Book Award-winning and #1 New York Times bestselling author (Praise for Punching the Air)

-

"Zoboi and Salaam have created nothing short of a masterwork of humanity, with lyrical arms big enough to cradle the oppressed, and metaphoric teeth sharp enough to chomp on the bitter bones of racism. This is more than a story. This is a necessary exploration of anger, and a radical reflection of love, which ultimately makes for an honest depiction of what it means to be young and Black in America."Jason Reynolds, NYT bestselling author of Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism, and You: A Remix (Praise for Punching the Air)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use