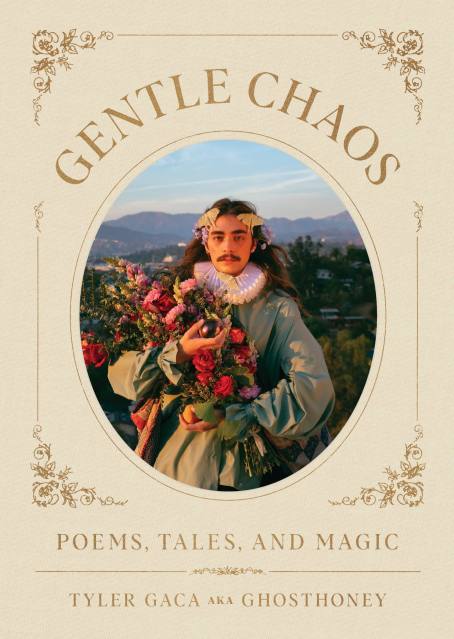

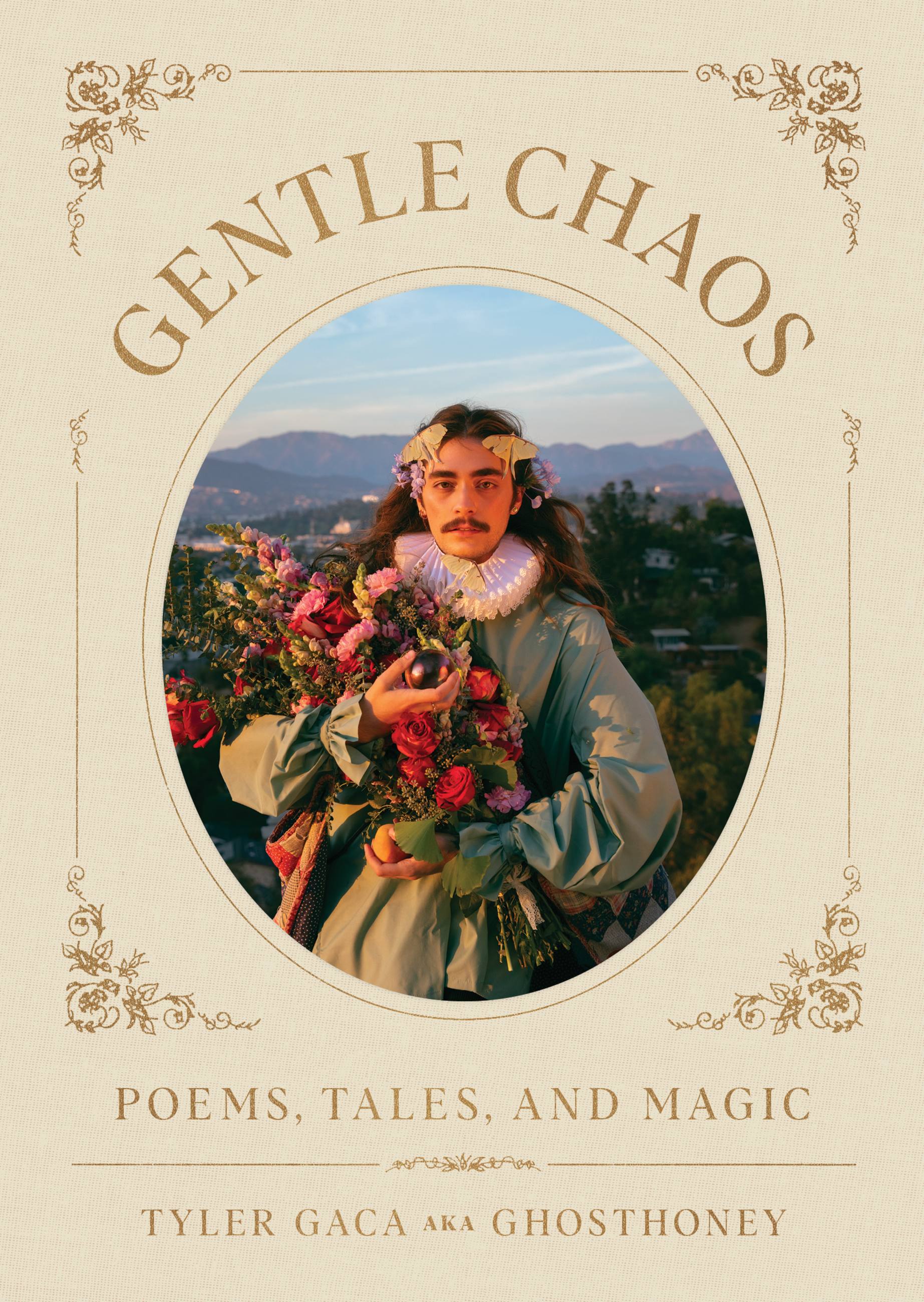

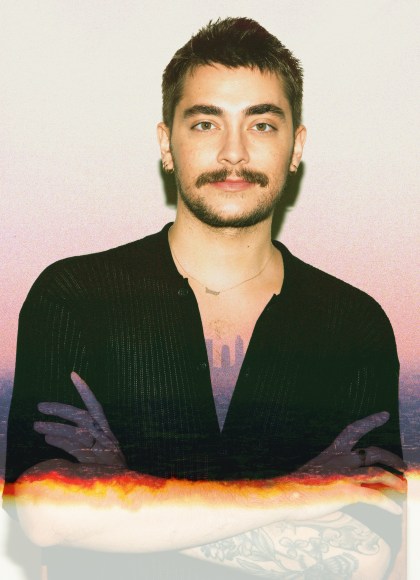

Exploring Gentle Chaos with Tyler Gaca aka @ghosthoney

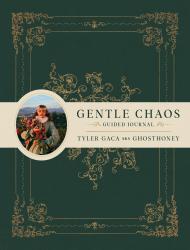

RP Mystic interviews Tyler Gaca aka @ghosthoney about the creation of Gentle Chaos: Poems, Tales, and Magic, a dreamy compendium of artworks written and visual that explore magic, queerness, Tyler’s unique story, and the enchantment and comfort to be found in the weird, the dark, and the different. Plus learn more about the companion Gentle Chaos Guided Journal and Gentle Chaos Pocket Oracle Deck.

Read full article