Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Treated Like Family

How an Entrepreneur and His "Employee Family" Built Sargento, a Billion-Dollar Cheese Company

Contributors

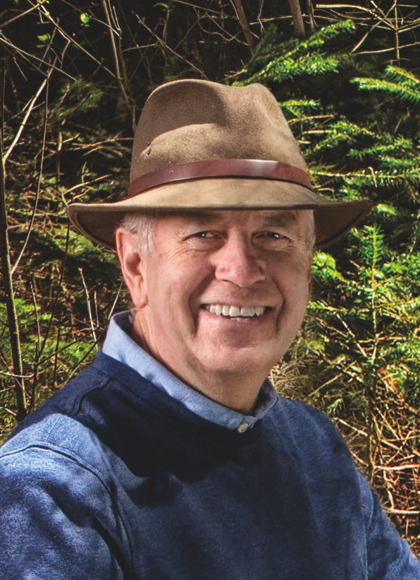

By Tom Faley

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 10, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

For Leonard, life didn’t prove that simple.

This biography, told from the viewpoint of four generations of the Gentine family, places the reader in Leonard’s shoes as he advances from young man to old age and discovers life’s foundational lessons. Along the way, he endures outstanding debts, disappointments, and a collection of small businesses, all with Dolores at his side. It’s an inspirational story of perseverance, personal integrity, and a mind-set of always doing the right thing-as painful as that may be in the short term.

Treated Like Family details the development of Sargento-a nationally recognized cheese company and household name. At the same time, it’s a timeless story that showcases the importance of the individual and how a family united in a single purpose within the right culture is unstoppable.

Tom Faley invites the reader into the lives of the Gentine family and the men and women they hired, deftly weaving a story grounded in over 180 interviews-the collective voices of the company’s employees, retirees, and friends.

Treated Like Family offers a rare glimpse into the creative mind of an innovator and entrepreneur and underscores the rewards for all of us when we maintain our humanity toward one another: When one person motivates others to pull together, at times facing unspeakable odds, he is able not only to change their lives but to alter history.

Genre:

-

"Believe it or not, a first generation American gets in an auto accident and takes a job at a funeral parlor to pay off damages to the owner's car... and then goes on to co-found a $1 billion, third-generation owned company whose success is based not just on innovation and quality but on treating employees like family. You'll love the fascinating and heartwarming story of Sargento Foods and its co-founder, Leonard Gentine."Jeff Haden, Inc.com contributing editor and author of The Motivation Myth

-

"When you visit a supermarket and peruse the aisles, there is a story and a history behind every brand that has a place on the shelf. The story of how the Gentines ideated, persevered, stumbled occasionally and ultimately architected and created one of America's most beloved brands is impressive. While the recipe for cheese starts with a 'culture,' it is in fact an adherence to a culture of dedication, appreciation for the contributions of others coupled with leadership and at times a little good luck that build a $1BB brand enjoyed by millions of consumers."Mitch Hersh, National Director of Sales, Florida's Natural Growers, a Division of Citrus World, Inc.

-

"TREATED LIKE FAMILY is an extremely well-written and engaging memoir of Leonard Gentine, the founder of Sargento. Its captivating stories pull the reader into the history of the company's growth, successes and setbacks as it explores how family values, woven into the fabric of his business, became one of Leonard's greatest achievements."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}span.s2 {font: 11.0px Helvetica; font-kerning: none}Dean R. Fowler, Ph.D., Family Business Consultant and Author of Love, Power and Money

-

Praise for the Audiobook:T.W. © AudioFile 2018, Portland, Maine

"Narrator Chris Ciulla's energetic phrasing and obvious enthusiasm for Leonard Gentine's story will keep listeners engaged with the many detailed anecdotes that lead up to the heart of his story-how one man's moral compass and respect for others lifted the lives of the many people who came to work with him at Sargento. Gentine owned a variety of businesses before he began selling gift boxes of cheese for companies to give to their employees. His journey from there to creating a national brand is illustrated with folksy tales of his perseverance, passion for fair play, and devotion to his family and employees. The author, who conducted more than 180 interviews with family and employees, also shows how Gentine's integrity and perseverance were rewarded by the loyalty he earned and the success he had as a business leader."

- On Sale

- Apr 10, 2018

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781478992868

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use