By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

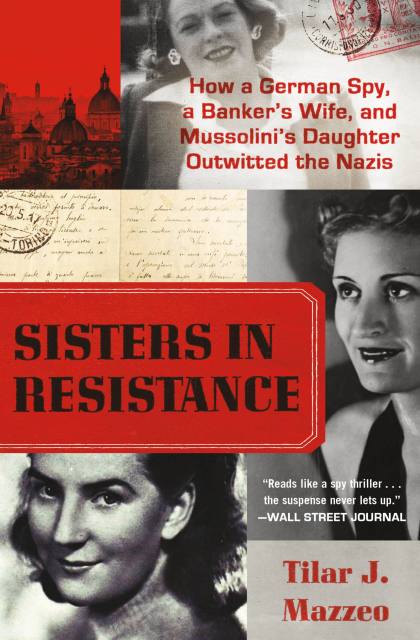

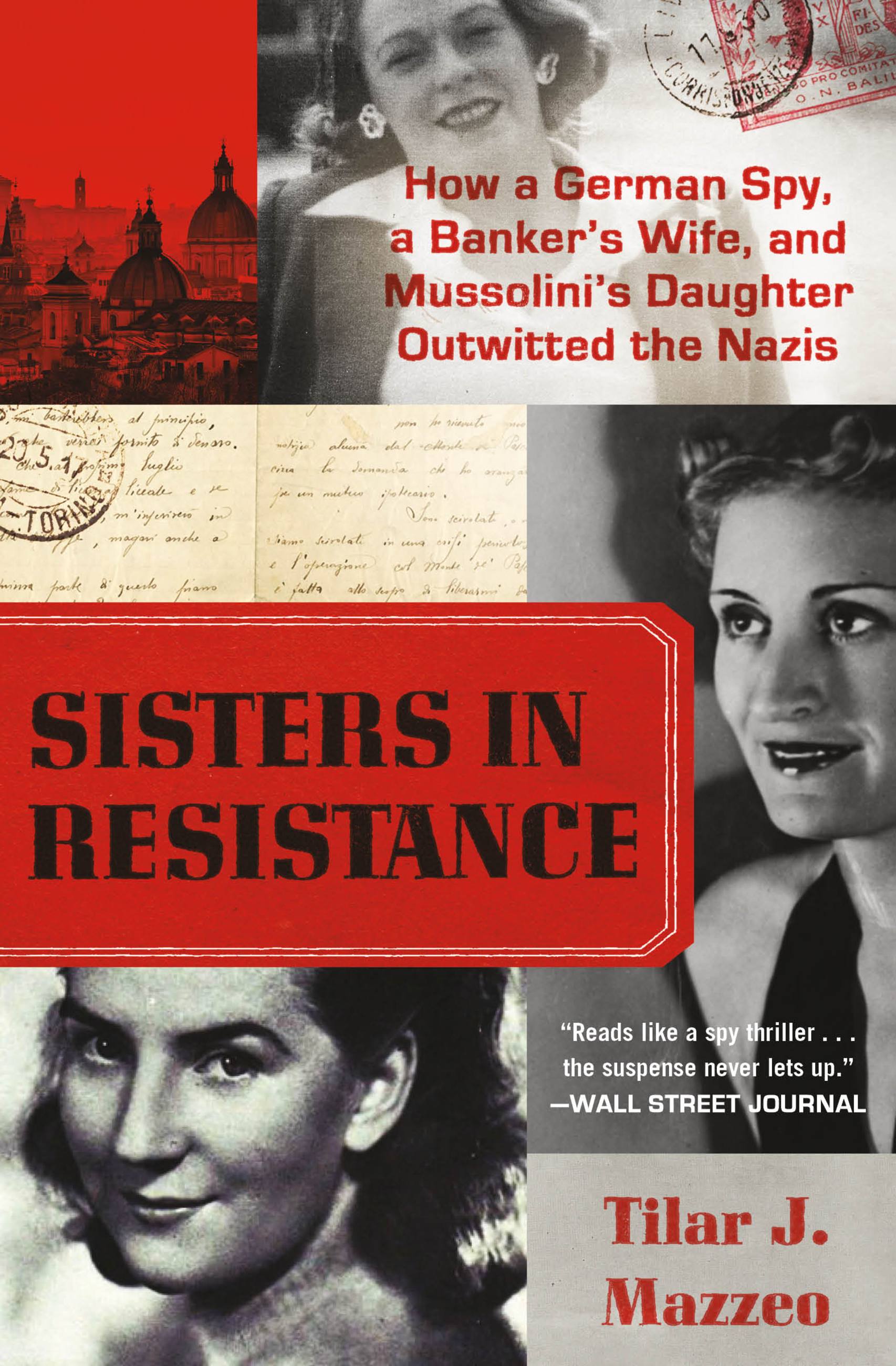

Sisters in Resistance

How a German Spy, a Banker's Wife, and Mussolini's Daughter Outwitted the Nazis

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 21, 2022

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538735275

Price

$14.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 21, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1944, news of secret diaries kept by Italy's Foreign Minister, Galeazzo Ciano, had permeated public consciousness. What wasn't reported, however, was how three women—a Fascist's daughter, a German spy, and an American banker’s wife—risked their lives to ensure the diaries would reach the Allies, who would later use them as evidence against the Nazis at Nuremberg.

In 1944, Benito Mussolini's daughter, Edda, gave Hitler and her father an ultimatum: release her husband, Galeazzo Ciano, from prison, or risk her leaking her husband's journals to the press. To avoid the peril of exposing Nazi lies, Hitler and Mussolini hunted for the diaries for months, determined to destroy them.

Hilde Beetz, a German spy, was deployed to seduce Ciano to learn the diaries' location and take them from Edda. As the seducer became the seduced, Hilde converted as a double agent, joining forces with Edda to save Ciano from execution. When this failed, Edda fled to Switzerland with Hilde’s daring assistance to keep Ciano's final wish: to see the diaries published for use by the Allies. When American spymaster Allen Dulles learned of Edda's escape, he sent in Frances De Chollet, an “accidental” spy, telling her to find Edda, gain her trust, and, crucially, hand the diaries over to the Americans. Together, they succeeded in preserving one of the most important documents of WWII.

Drawing from in‑depth research and first-person interviews with people who witnessed these events, Mazzeo gives readers a riveting look into this little‑known moment in history and shows how, without Edda, Hilde, and Frances's involvement, certain convictions at Nuremberg would never have been possible.

Includes a Reading Group Guide.

Genre:

-

"Compelling . . . a tangled web of deceit, corruption, betrayal, courage, and family intrigue. It reads like a spy thriller, moving at a fast pace, and even though the reader knows the successful outcome, the suspense never lets up."Wall Street Journal

-

"Intelligent and compelling, Mazzeo’s probing book delves intriguingly into the “moral thicket” into which a group of strangers found themselves plunged during the long, dark days of World War II. A tantalizingly novelistic history lesson."Kirkus

-

"Mazzeo efficiently relates these complex events and renders empathetic portraits of the story’s main players. WWII buffs will be enthralled."Publishers Weekly

-

"Reads like a John le Carré novel, too incredible to be true—and yet it is . . . This little-known but very important WWII story has the pacing of a thriller novel with the research acumen expected from this excellent writer."Booklist

-

"A nail-biting account of state crimes and secrets, real world action pitting spy versus spy and diplomat versus diplomat."Library Journal

-

"A little-known history finally comes to light in Sisters in Resistance."Town and Country

-

"Mazzeo’s latest deep dive into fascinating, complicated women . . . A gripping novelistic history lesson that reads like a plot plucked from a Ken Follett or Alan Furst spy novel–except it all happened."Zoomer

-

“An important, often harrowing, and until now little-known story of the Holocaust: how thousands of children were rescued from the Warsaw ghetto by a Polish woman of extraordinary daring and moral courage.”Joseph Kanon, Author of Leaving Berlin, Praise for Irena’s Children

-

“Mazzeo chronicles a ray of hope in desperate times in this compelling biography of a brave woman who refused to give up.”Kirkus Reviews, Praise for Irena's Children

-

“Mazzeo reveals a hotbed of illicit affairs and deadly intrigue, as well as stunning acts of defiance and treachery.”Brad Thor, The Today Show Summer Reads, Praise for The Hotel on Place Vendome

-

"Tilar J. Mazzeo lifts the veil to reveal a lesser-known narrative of scandal and subterfuge . . . A work of history that reads as enticingly as a novel."Harper's Bazaar, Praise for Hotel on Place Vendome

-

“An enticing stew of biography and history.”USA Today, Praise for The Widow Clicquot

-

“The story of a woman who was a smashing success long before anyone conceptualized the glass ceiling.”New York Times Book Review, Praise for The Widow Clicquot

-

“A magnificent window through which to understand [Coco Chanel] and her milieu . . . Impeccable research and crafting make a seemingly narrow topic feel infinitely important.”Kirkus Reviews, Praise for The Secret of Chanel No. 5

-

“Vivid, compelling, and unputdownable . . . Eliza Hamilton finally takes her place in the pantheon of remarkable American women who, no less than the men they loved, built this nation.”Christopher Andersen, #1 New York Times bestselling author, Praise for Eliza Hamilton

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use