Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

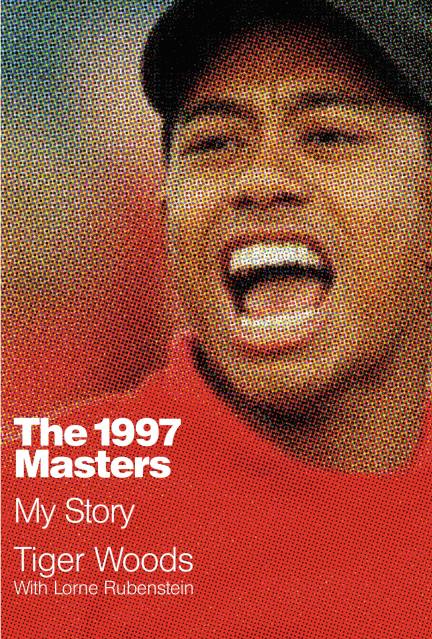

The 1997 Masters

My Story

Contributors

By Tiger Woods

With Lorne Rubenstein

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 20, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In 1997, Tiger Woods was already among the most-watched and closely examined athletes in history. But it wasn’t until the Masters Tournament that his career would definitively change forever. Woods, then only 21, won the Masters by a historic 12 shots, which remains the widest margin of victory in the tournament’s history, making it an iconic moment for him and sports.

Now, Woods is ready to explore his history with the game, how it has changed over the years, and what it was like winning such an important event. With never-before-heard stories, this book will provide keen insight from one of the game’s all-time greats.

Genre:

-

"[Woods's] memories of what happened that now-long-ago April in Augusta... will resonate with anyone who follows golf and especially with everyone who was riveted to their televisions as this brash, incredibly talented young man dismantled the cathedral of golf."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Provides a rare perspective of golf played at the highest level."Kirkus

-

"Woods writes with absorbing focus and profound emotion."Publishers Weekly

-

"THE 1997 MASTERS is a vivid and ultimately satisfying read about a singular event in American sports."BookPage

-

"For as methodical as Woods tells his story-his recall of every shot and situation is all as if it were 20 minutes ago, not 20 years-it is often as vivid on the printed page as it was in person."GolfDigest

-

"Readers get to go behind the scenes and on the golf course with compelling stories and anecdotes from that fateful April week at Augusta two decades ago. That's not all. Intertwined throughout are shared opinions from Woods on an array of topics and issues, most golf related, some personal and societal based, but all presented with candour and intrigue. Such is the riveting nature of arguably the world's most recognizable athlete."ScoreGolf

- On Sale

- Mar 20, 2017

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455571505

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use