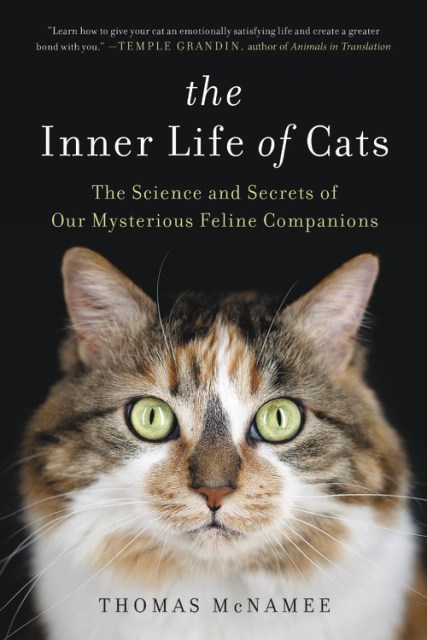

The Inner Life of Cats

The Science and Secrets of Our Mysterious Feline Companions

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 27, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As it begins, The Inner Life of Cats follows the development of the young Augusta while simultaneously explaining the basics of a kitten’s physiological and psychological development. As the narrative progresses, McNamee also charts cats’ evolution, explores a feral cat colony in Rome, tells the story of Augusta’s life and adventures, and consults with behavioral experts, animal activists, and researchers, who will help readers more fully understand cats.

McNamee shows that with deeper knowledge of cats’ developmental phases and individual idiosyncrasies, we can do a better job of guiding cats’ maturation and improving the quality of their lives. Readers’ relationships with their feline friends will be happier and more harmonious because of this book.

Genre:

-

"This deeply researched book helps us understand how our cats experience the world and what they are trying to communicate to us."Catster

-

"The Inner Life of Cats is filled with shining prose, moments of sheer cat joy--and intimate, careful scientific observation. Thomas McNamee's naturalist's eye, combined with his humor and heart, bring the always wild, yet domesticated cat into delightful, insightful focus."Cat Warren, New York Times bestselling author of Whatthe Dog Knows

-

"Learn how to give your cat an emotionally satisfying life and create a greater bond with you."Temple Grandin,author of Animals in Translation

-

"[An] affectionate love letter to his own cat Augusta and a perceptive analysis of feline psychology and biology that shatters common assumptions about these animals."Library Journal

-

"Tom McNamee has provided a great service not just to cat lovers but to people like me, who don't much care for them. In this wise, humane, deeply researched book, he makes a persuasive case that these creatures are much more interesting, mysterious, and complicated than we ever gave them credit for. And they probably have misgivings about some of us, too."Charles McGrath,former editor, New York Times Book Review

-

"An affectionate yet realistic portrait of felis silvestris catus and a definite boon to anyone contemplating adopting a cat."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Cats are fascinating beings who often get the short end of the stick when they're casually and wrongly dismissed as mysterious, solitary, and unemotional animals when compared, for example, to dogs, or when they're accused of being vicious predators on wildlife. In fact, cats, just like Mr. McNamee's beloved Augusta, are highly intelligent, emotional, and sentient animals who have rich and deep inner lives, as well documented in this seminal book in which heartwarming stories and scientific data are nicely woven together. Thomas McNamee's latest book is a much needed corrective and myth-buster for which cat lovers and cats around the world will be most grateful."Marc Bekoff, author of The Animals' Agenda: Freedom, Compassion, andCoexistence in the Human Age

-

"Elegant and absorbing, The Inner Life of Cats offers fascinating insights into the interior world of these mysterious and compelling animals. Required reading for anyone who lives with, loves, or has ever wondered about the deep and ancient connections we share with these magnificent creatures."BarbaraNatterson-Horowitz, MD and Kathryn Bowers, co-authors of Zoobiquity: TheAstonishing Connection Between Human and Animal Health

-

"To see an animal in so many ways: as a scientist, a naturalist, a human being, and a writer of uncommon sensitivity, this is Tom McNamee's The Inner Life of Cats; and this book is a gift."Dorothy Kalins,founding editor, Saveur

-

"The Inner Life of Cats is a remarkably charming, intelligent, and heartfelt book about cats and humans. In places it moved me to tears and, at other places, to broad grins. Thomas McNamee has brilliantly combined his own experiences with cats and information gleaned from scientific studies, all in immensely readable pages. Every cat-lover should read this fine book."Pat Shipman, authorof The Animal Connection: A New Perspective on What Makes Us Human

-

"This entertaining but serious book tells everything of the complex relationship between humans and cats. Tom McNamee, in a lively and insightful account, explores the relationship from all angles, explaining the many opportunities and consequences of living with cats. This book, written in conversational language and easy to read, is filled with fascinating anecdotes, a wealth of scientific data and a great deal of thoughtful meditations. It is a complete reference on these elusive companions and it offers a passionate but objective perspective. You will find a lot to learn, regardless whether you love or hate cats!"Luigi Boitani, co-author of Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation

-

"A compelling and profoundly rich account of the inner life of cats: you will never think of a cat except in admiration. A great read."Thomas E. Lovejoy,University Professor of Environmental Science and Policy, George MasonUniversity

-

"As a conservation biologist, I have mixed emotions about cats. I am all too aware of the damage free-roaming cats do to bird populations and other wildlife, but on the other hand some of my best friends have been cats. Thomas McNamee has written a sensitive, sometimes heart-wrenching, but scientifically accurate book about these beguiling creatures and their amazing attributes. This book objectively addresses the feral cat issue as the serious problem it is. Yet, readers (sometimes teary-eyed) likely will be convinced that a cat is 'pure awareness' and, despite its craziness, quite capable of mutual love with its human companions."Reed F. Noss, author of The Science of Conservation and Provost'sDistinguished Research Professor, Department ofBiology, University ofCentral Florida

-

"It is so important to dispel the many myths surrounding these majestic animals. This book is steeped in honesty, it's informative, extremely well-written, and truly a must for all those who would like a better understanding of and a better relationship with their cats. It is written with such an abiding love and respect for these largely misunderstood creatures, that one cannot help but be moved."Bonnie Berman, Topical Currents, WLRN

-

"Riveting."The Virginian-Pilot

-

"I . . . was charmed by McNamee's tale of his cat, Augusta, and his attempts to understand this essentially unknowable (but lovable) animal. The Inner Life of Cats is Augusta's life story, an engaging one interspersed with plentiful information about cats."Washington Post

-

"The Inner Life of Cats is a wonderful blend of science and stories . . . cats often are misunderstood and [this] wonderful book is a much needed corrective and myth-buster for which cat lovers and cats around the world will be most grateful."Psychology Today

- On Sale

- Mar 27, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316262903

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use