By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

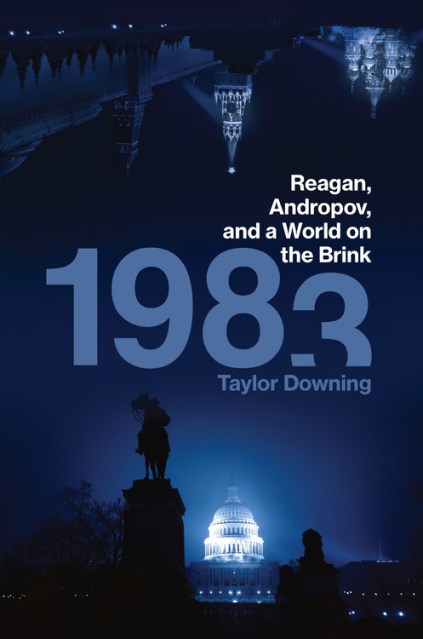

1983

Reagan, Andropov, and a World on the Brink

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 24, 2018

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306921728

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $35.00 $45.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 24, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The year 1983 was an extremely dangerous one–more dangerous than 1962, the year of the Cuban Missile Crisis. In the United States, President Reagan vastly increased defense spending, described the Soviet Union as an “evil empire,” and launched the “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative to shield the country from incoming missiles. Seeing all this, Yuri Andropov, the paranoid Soviet leader, became convinced that the US really meant to attack the Soviet Union and he put the KGB on high alert, looking for signs of an imminent nuclear attack.

When a Soviet plane shot down a Korean civilian jet, Reagan described it as “a crime against humanity.” And Moscow grew increasingly concerned about America’s language and behavior. Would they attack? The temperature rose fast. In November the West launched a wargame exercise, codenamed “Abel Archer,” that looked to the Soviets like the real thing. With Andropov’s finger inching ever closer to the nuclear button, the world was truly on the brink.

This is an extraordinary and largely unknown Cold War story of spies and double agents, of missiles being readied, intelligence failures, misunderstandings, and the panic of world leaders. With access to hundreds of astonishing new documents, Taylor Downing tells for the first time the gripping but true story of how near the world came to nuclear war in 1983.

-

"A gripping and frankly terrifying book on the US-Soviet nuclear confrontation"--Tom Holland, award-winning author of Rubicon and Dynasty

-

"Carefully-researched and absorbing."Christian Science Monitor

-

"A terrific book that should terrify anyone who reads it. It is a must-read for students of the Cold War and for anyone who thinks nuclear brinkmanship is a productive way to conduct foreign policy."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"The most readable version to date of an episode that holds lessons for today."The Nation

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use