By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

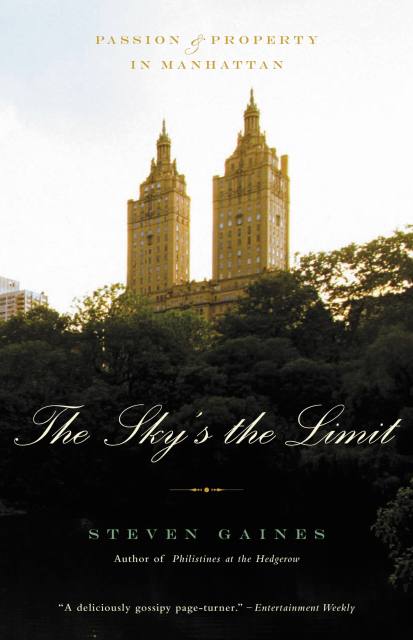

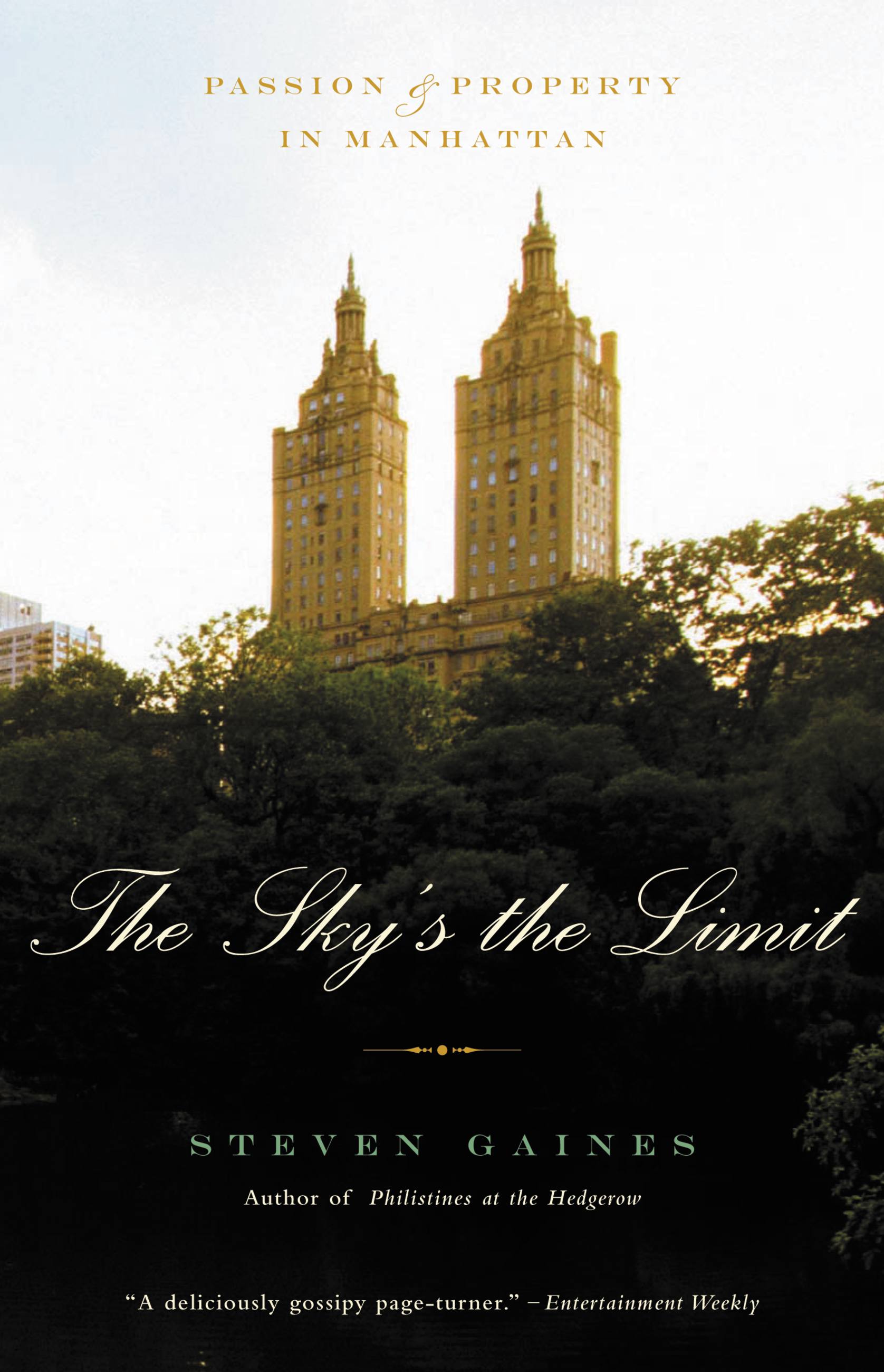

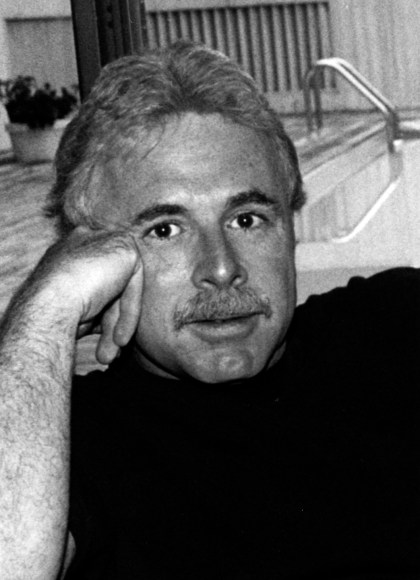

The Sky’s the Limit

Passion and Property in Manhattan

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2005

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780759513884

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Gaines uncovers the secretive, unwritten rules of co-op boards: why diplomats and pretty divorcees are frowned upon, what not to wear to a board interview, and which of the biggest celebrities and CEOs have been turned away from the elite buildings of Fifth and Park Avenues. He introduces the carriage-trade brokers who never have to advertise for clients and gives us finely etched portraits of a few of the discreet, elderly society ladies who decide who gets into the so-called Good Buildings.

Here, too, is a fascinating chronicle of the changes in Manhattan’s residential skyline, from the slums of the nineteenth century to the advent of the luxury building. Gaines describes how living in boxes stacked on boxes came to be seen as the ultimate in status, and how the co-operative apartment, originally conceived as a form of housing for the poor, came to be used as a legal means of black-balling undesirable neighbors.

A social history told through brick and mortar, The Sky’s the Limit is the ultimate look inside one of the most exclusive and expensive enclaves in the world, and at the lengths to which people will go to get in.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use