By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

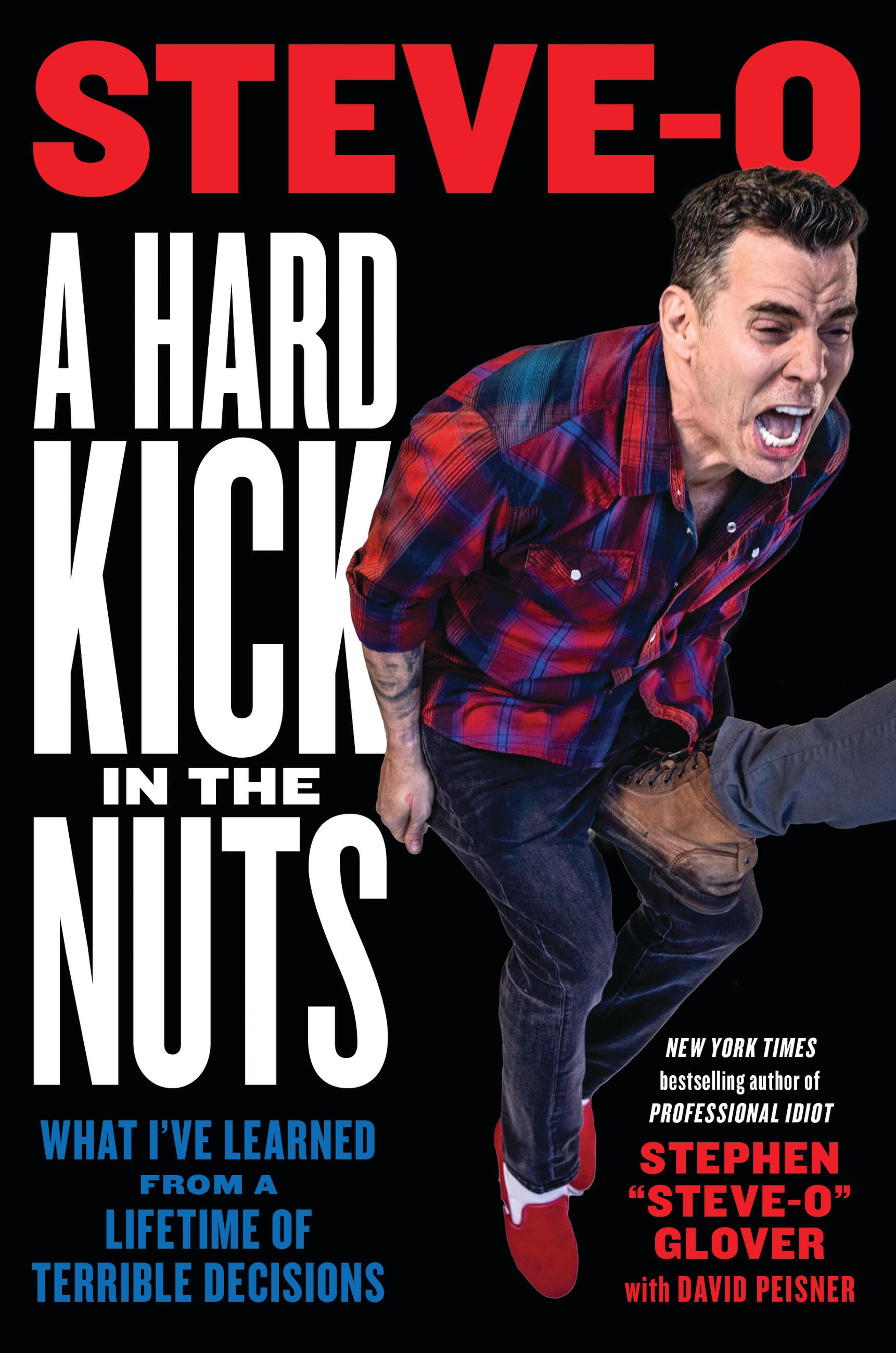

A Hard Kick in the Nuts

What I've Learned from a Lifetime of Terrible Decisions

Contributors

With David Peisner

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 27, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826771

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 27, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Stephen "Steve-O" Glover—social media icon, comedy-touring stalwart, and star of Jackass—delivers a hilarious and practical guide to recovery, relationships, career, and how to keep thriving long after you should be dead.

Steve-O is best known for his wildly dangerous, foolish, painful, embarrassing, and sometimes death-defying stunts. At age 48, however, he faces his greatest challenge yet: getting older. A Hard Kick in the Nuts: What I’ve Learned from a Lifetime of Terrible Decisions is a captivating exploration of life and how to live it by an individual who has already lived way more than a lifetime’s worth of extreme experiences. Steve-O grapples with the right balance between maturity and staying true to yourself, not repeating your “greatest hits,” maintaining sobriety and a healthy regimen, avoiding selfishness, and finding the right partner for life.Having built a gargantuan and loyal social media following while establishing a successful stand-up career—all after a couple of decades of dubious behavior—Steve-O is proof that anyone can find meaning and fulfillment in life, no matter what path they choose. Packed with self-deprecating wit and gruelingly earned wisdom, A Hard Kick in the Nuts will reverberate with readers everywhere who have lived a lot (sometimes too much) and are now wondering how to approach the years to come. Or maybe just need some good motivation to get out of bed tomorrow. One of many tips: Be your own harshest critic, then cut yourself a break, and enjoy this book.

-

“I read this book all in one sitting. I am first of all blown away by Steve-O’s continued sobriety and also his honesty and complete transparency in writing this wonderful book. Eternally proud of my brother.”Johnny Knoxville

-

“Dude, this book is wildly engrossing. I finished it in almost three hours, and I literally hate books. Just when I thought I couldn’t have seen more of Steve's private parts, he managed to bare even more stuff that most people would deny 'til their dying day. The results are riveting, hilarious, and shockingly educational.”Whitney Cummings

-

“The way Steve-O has turned his life around is just incredible. It’s all in this book!”Dana White, President of the Ultimate Fighting Championship

-

“Thoughtful and revealing, but on-brand….The new book is filled with profound observations and frank revelations. If the first [book] goes to the bone, this one goes to the marrow."CBS Saturday Morning

-

“A disarmingly direct memoir of mistakes and course corrections studded with some useful advice.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“While one might not expect to find wisdom in a hilarious tale about belly-flopping into a urine-filled kiddie pool, Glover is a veritable expert at learning 'some valuable shit from [a] lifetime of terrible decisions.' Dick jokes aside, this is full of heart and hard-won insight.”Publishers Weekly

-

Praise for Professional Idiot

-

"A great book to read before you get on the roller coaster to hell, if you plan on surviving to tell about it like Steve-O did."Nikki Sixx, author of The Heroin Diaries

-

"This is the perfect book for people who hate reading."Tommy Lee, author of Tommyland

-

"It's mind-blowing to me how utterly far gone Steve-O was, and how he looks back on it in this book with such intelligence, humor, and searing honesty. What a truly unbelievable life."Johnny Knoxville

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use