Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

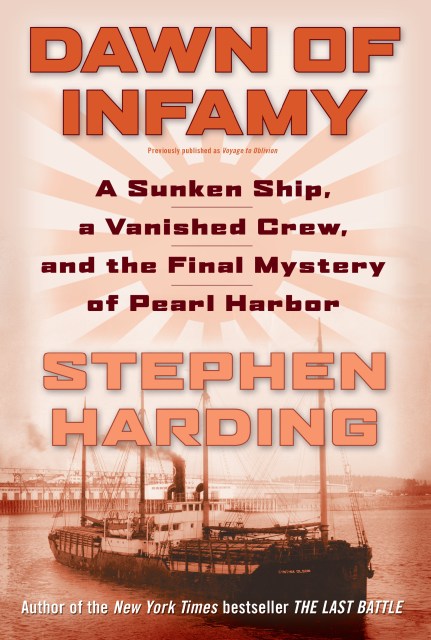

Dawn of Infamy

A Sunken Ship, a Vanished Crew, and the Final Mystery of Pearl Harbor

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $15.99 $20.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 22, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On December 7, 1941, even as Japanese carrier-launched aircraft flew toward Pearl Harbor, a small American cargo ship chartered by the Army reported that it was under attack by a submarine halfway between Seattle and Honolulu. After that one cryptic message, the humble lumber carrier Cynthia Olson and her crew vanished without a trace, their disappearance all but forgotten as the mighty warships of the U.S. Pacific Fleet burned.

The story of the Cynthia Olson‘s mid-ocean encounter with the Japanese submarine I-26 is both a classic high-seas drama and one of the most enduring mysteries of World War II. Did I-26‘s commander, Minoru Yokota, sink the freighter before the attack on Pearl Harbor began? Did the cargo ship’s 35-man crew survive in lifeboats that drifted away into the vast Pacific, or were they machine-gunned to death? Was the Cynthia Olson the first American casualty of the Pacific War, and could her SOS have changed the course of history?

Based on years of research, Dawn of Infamy explores both the military and human aspects of the Cynthia Olson story, bringing to life a complex tale of courage, tenacity, hubris, and arrogance in the opening hours of America’s war in the Pacific.

Genre:

-

Library Journal, 9/15/16

“Harding's thorough research reconstructs the Cynthia Olson's last days…While the story of the Cynthia Olson often appears as a side note in other histories about Pearl Harbor, this harrowing account brings it to the fore, telling how a Japanese submarine was able to sail close to the U.S. mainland and sink an unarmed ship in the hours before America entered World War II…Will appeal to nautical and military historians alike.”

Kirkus Reviews, 10/15/16

“A detailed, well-researched book presented in a logical fashion—will appeal most to Pearl Harbor scholars and those interested in submarine warfare.”

-

"An account of a little known incident that might have seen the opening shots of the Japanese war against the United States...Their story needed to be told."New York Journal of Books

-

Stone & Stone

"Harding takes a minor incident that could be reduced to a single sentence and, despite the lack of hard information about many aspects of the event, turns it into a fast-paced piece of historical detective work with very human dimensions and consequences...An engaging and satisfying book."

-

"Based on years of research, Dawn of Infamy explores both the military and human aspects of the Cynthia Olson story, bringing to life a complex tale of courage, tenacity, hubris and arrogance in the opening hours of America's war in the Pacific."Bookreporter.com

-

"Stephen Harding researched a small part of World War II military history...with the amazing details typical of a good journalist."Seattle Book Review

-

"Harding brings his expert skills as a researcher and writer to this little known subject...An excellent look at a long-forgotten story that occurred at the beginning of American involvement in World War II in the Pacific."Collected Miscellany

-

"Rich in detail...A well-written and convincing book about an interesting historical sidelight...The author has done a good job of weaving together a mass of disparate evidence and technical information."Warship International

-

"The book's engaging storyline will appeal to both nonspecialists and military historians with an interest in the early years of the Pacific War. Its narrative style and subject matter evoke nautical adventure books like Sebastian Junger's The Perfect Storm and Nathaniel Philbrick's In the Heart of the Sea...Gripping."Michigan War Studies Review

- On Sale

- Nov 22, 2016

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825040

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use