By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

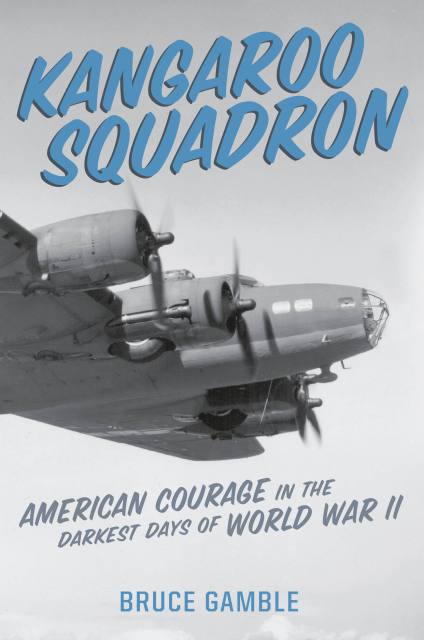

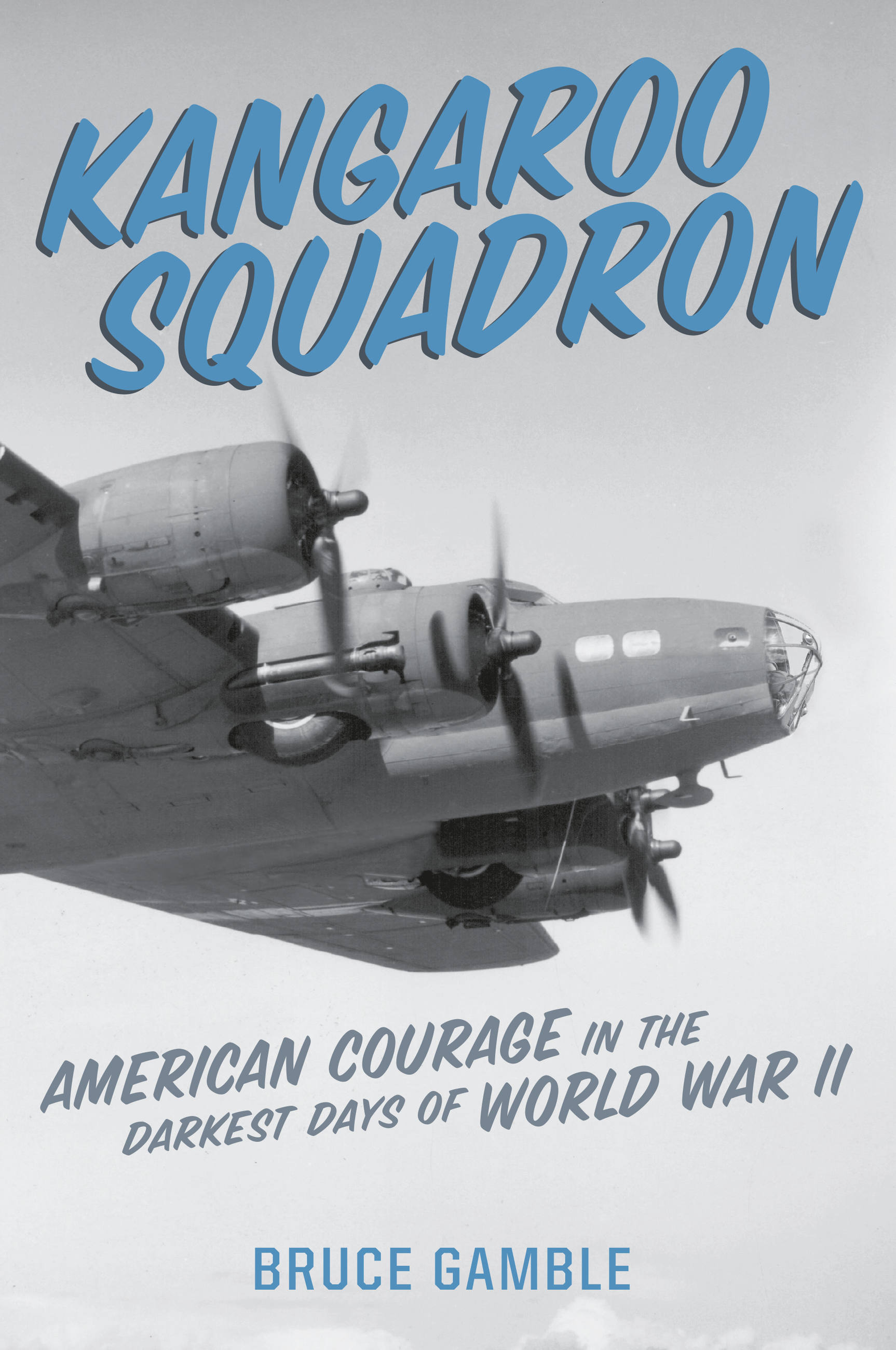

Kangaroo Squadron

American Courage in the Darkest Days of World War II

Contributors

By Bruce Gamble

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306903120

Price

$28.00Price

$36.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Based in Australia with inadequate supplies and no ground support, the squadron’s pilots and combat crew endured tropical diseases while confronting numerically superior Japanese forces. Yet the outfit, dubbed the Kangaroo Squadron, proved remarkably resilient and successful, conducting long-range bombing raids, carrying out armed reconnaissance missions, and rescuing General MacArthur and his staff from the Philippines.

Before now, the story of their courage and determination in the face of overwhelming odds has largely been untold. Using eyewitness accounts from diaries, letters, interviews, and memoirs, as well as Japanese sources, historian Bruce Gamble brings to vivid life this dramatic true account.

But the Kangaroo Squadron’s story doesn’t end in World War II. One of the squadron’s B-17 bombers, which crash-landed on its first mission, was recovered from New Guinea after almost seventy years in a jungle swamp. The intertwined stories of the Kangaroo Squadron and the “Swamp Ghost” are filled with thrilling accounts of aerial combat, an epic survival story, and the powerful mystique of an invaluable war relic.

-

"In the darkest days of World War II in the Pacific, a squadron of forgotten heroes gave their all, becoming the first to strike back against the Japanese. Kangaroo Squadron is an inspiring, beautifully crafted tale of ordinary Americans exhibiting extraordinary heroism and grit when it mattered most."--Alex Kershaw, New York Times bestselling author of The Longest Winter and The First Wave

-

"Bruce Gamble has beautifully captured the dark early days of World War II--and the brave American airmen willing to take the fight to the enemy. With a novelists's gift for storytelling, Gamble takes readers into cockpits over Japanese bases, drops them waist-deep in malarial swamps, and lets them unwind in dusty outback bars. Kangaroo Squadron is a soaring story and a triumph of the American spirit."--James M. Scott, Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of Rampage and Target Tokyo

-

"With his exquisite eye for detail and spellbinding talent as a stroyteller, Bruce Gamble takes readers on an unforgettable journey through the perilous early months of World War II in the Southwest Pacific."--Colonel Walter Boyne, author and former director of the National Air and Space Museum

-

"Fast-paced and packed with vivid descriptions and valuable information, Kangaroo Squadron shines a bright light on the valiant American fliers who took on the Japanese in the first engagements in the Pacific. Bruce Gamble brings these heroes out of the shadows and makes them come alive. A must-read for anyone interested in World War II."--John Darnton, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Almost a Family

-

"Bruce Gamble demonstrates again why he is one of the best aviation historians in the business. In Kangaroo Squadron he has crafted a fascinating account of men and machines, painting a compelling picture of what it was like to fight as an American aviator during the very darkest days of the Pacific War. Outstanding!"--Jonathan Parshall, co-author of Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway

-

"Bruce Gamble's excellent history of the U.S. Army's B-17 bombers in the Pacific, officially the Southern Bomber Command but colloquially known as the Kangaroo Squadron, is a triumph. The characters are vivid and the narrative gripping; the story of the downed B-17 later known as the 'Swamp Ghost' is especially riveting. Throughout, Gamble's mastery of aircraft characteristics is impeccable, and his fast-paced storytelling is irresistible."--Craig L. Symonds, author of World War II at Sea: A Global History

-

"Flying Boeing B-17s, the Kangaroo Squadron's aircrews and maintenance men fought not only Imperial Japan but weather, geography, and a perennial shortage of everything--except courage and dedication. Their example remains an inspiration to Americans three generations later, thanks to Bruce Gamble's in-depth research and deft writing."--Barrett Tillman, author of On Wave and Wing: The 100-Year Quest to Perfect the Aircraft Carrier

-

"Gamble has a solid grasp of big-picture strategy and of the alternating tedium and terror of war, especially as bomber crews experienced it, never knowing when anti-aircraft fire would take them down or the fuel would run out before they could return to base."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Gamble delivers an inspiring and impeccably researched tale...Both the air war expert and the general reader will enjoy and learn something from this well-crafted work."Publishers Weekly

-

"Gamble is a fine story-teller. His narrative in Kangaroo Squadron is fast-moving and full of vivid descriptions and moving detail of a group of American warriors that deserve to be remembered with gratitude."American Spectator

-

"Brims with heroism in the face of seemingly impossible odds...a well-written and informative examination of the air war."Washington Times