By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

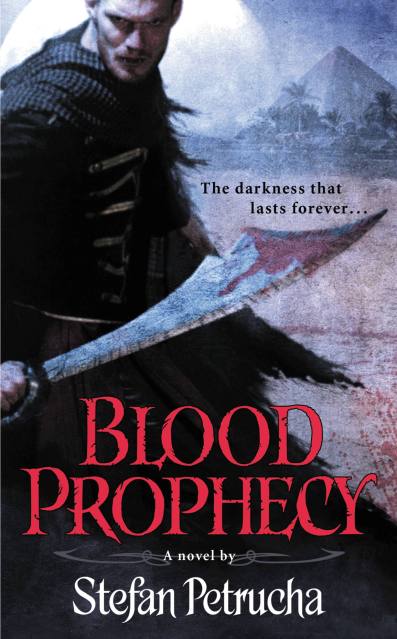

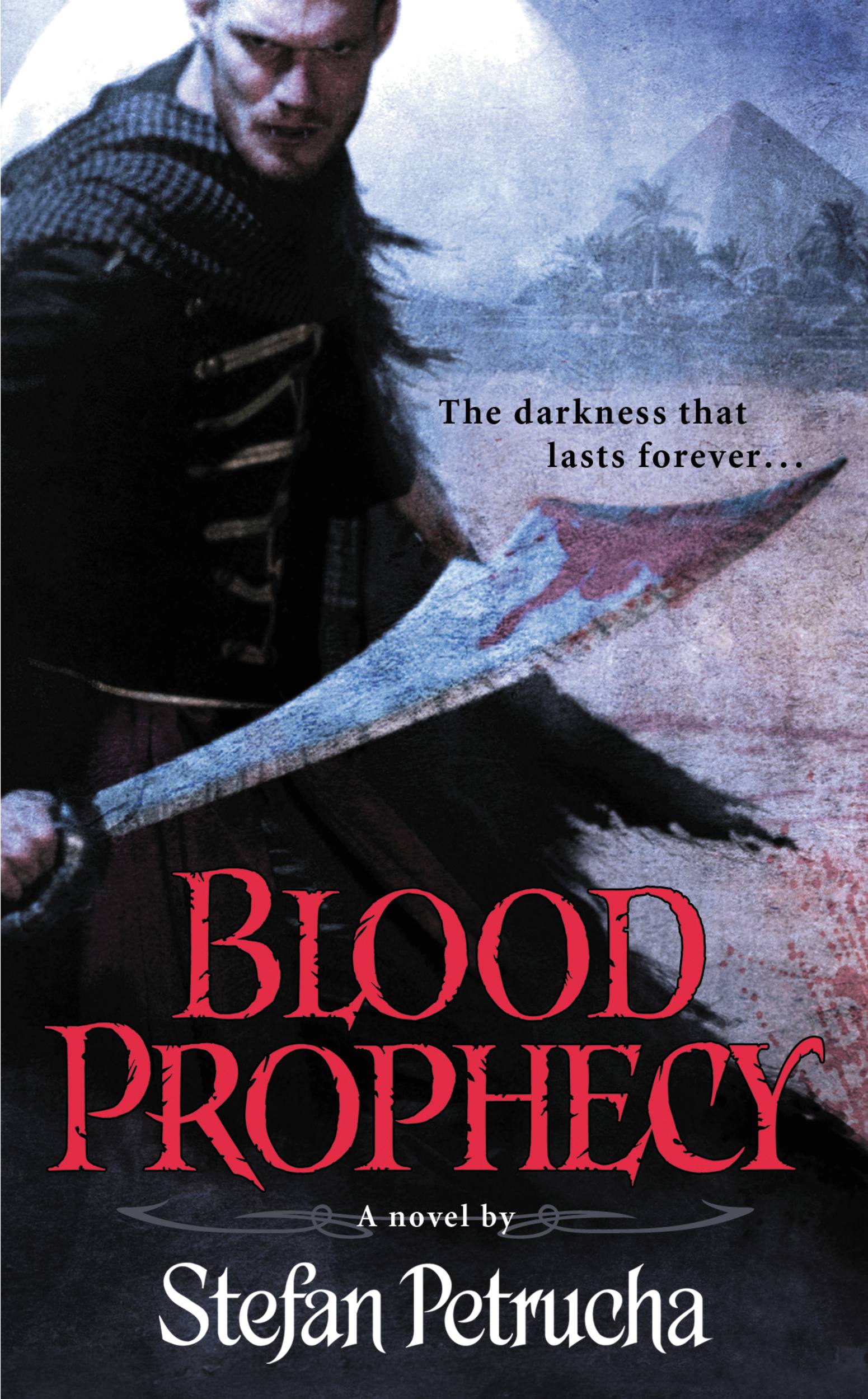

Blood Prophecy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 1, 2010

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446584449

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $7.99 $9.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 1, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Man and monster are in his blood. . .

His name is Jeremiah Fall. A soldier of fortune, he has been fighting his own war for 150 years–ever since the beast in him was born.

Desperate to restore his lost humanity, Fall crosses the sands of Egypt, discovers a lost city off the coast of France, and finally arrives at the birthplace of all mankind. Shunning daylight and feeding only when he must, he battles the monster who transformed him forever. He can share his deepest secret with no one . . . not even the beautiful woman he starts to love, the only human who grasps the mysteries of an ebony stone as old as creation itself.

Across the world, across time, Fall seeks the stone’s secret. But has he found a cure for himself or unleashed a final curse on all mankind?

His name is Jeremiah Fall. A soldier of fortune, he has been fighting his own war for 150 years–ever since the beast in him was born.

Desperate to restore his lost humanity, Fall crosses the sands of Egypt, discovers a lost city off the coast of France, and finally arrives at the birthplace of all mankind. Shunning daylight and feeding only when he must, he battles the monster who transformed him forever. He can share his deepest secret with no one . . . not even the beautiful woman he starts to love, the only human who grasps the mysteries of an ebony stone as old as creation itself.

Across the world, across time, Fall seeks the stone’s secret. But has he found a cure for himself or unleashed a final curse on all mankind?

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use