Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

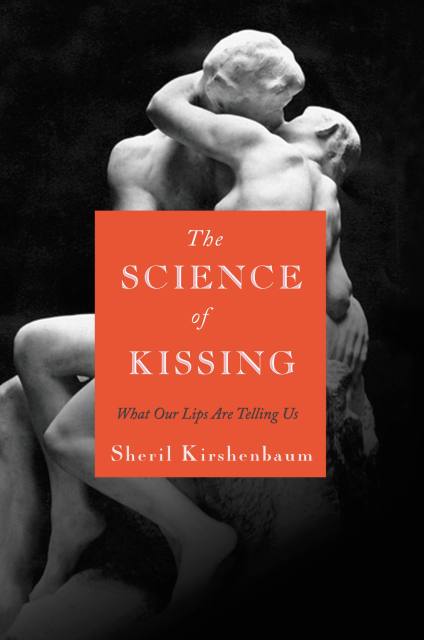

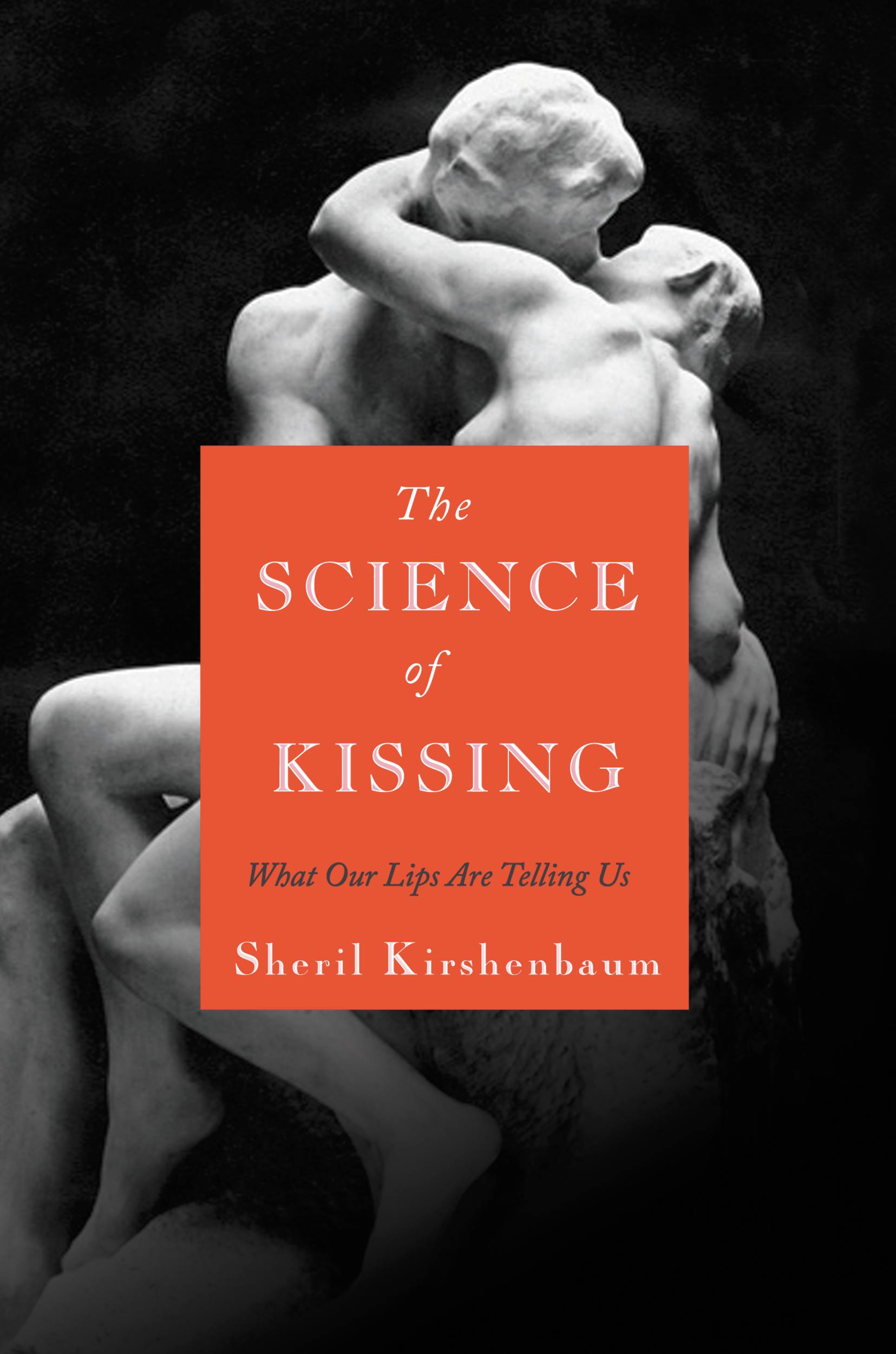

The Science of Kissing

What Our Lips Are Telling Us

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 5, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From a noted science journalist comes a wonderfully witty and fascinating exploration of how and why we kiss.

When did humans begin to kiss? Why is kissing integral to some cultures and alien to others? Do good kissers make the best lovers? And is that expensive lip-plumping gloss worth it? Sheril Kirshenbaum, a biologist and science journalist, tackles these questions and more in The Science of a Kiss. It’s everything you always wanted to know about kissing but either haven’t asked, couldn’t find out, or didn’t realize you should understand.

The book is informed by the latest studies and theories, but Kirshenbaum’s engaging voice gives the information a light touch. Topics range from the kind of kissing men like to do (as distinct from women) to what animals can teach us about the kiss to whether or not the true art of kissing was lost sometime in the Dark Ages. Drawing upon classical history, evolutionary biology, psychology, popular culture, and more, Kirshenbaum’s winning book will appeal to romantics and armchair scientists alike.

When did humans begin to kiss? Why is kissing integral to some cultures and alien to others? Do good kissers make the best lovers? And is that expensive lip-plumping gloss worth it? Sheril Kirshenbaum, a biologist and science journalist, tackles these questions and more in The Science of a Kiss. It’s everything you always wanted to know about kissing but either haven’t asked, couldn’t find out, or didn’t realize you should understand.

The book is informed by the latest studies and theories, but Kirshenbaum’s engaging voice gives the information a light touch. Topics range from the kind of kissing men like to do (as distinct from women) to what animals can teach us about the kiss to whether or not the true art of kissing was lost sometime in the Dark Ages. Drawing upon classical history, evolutionary biology, psychology, popular culture, and more, Kirshenbaum’s winning book will appeal to romantics and armchair scientists alike.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 5, 2011

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446575133

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use