Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

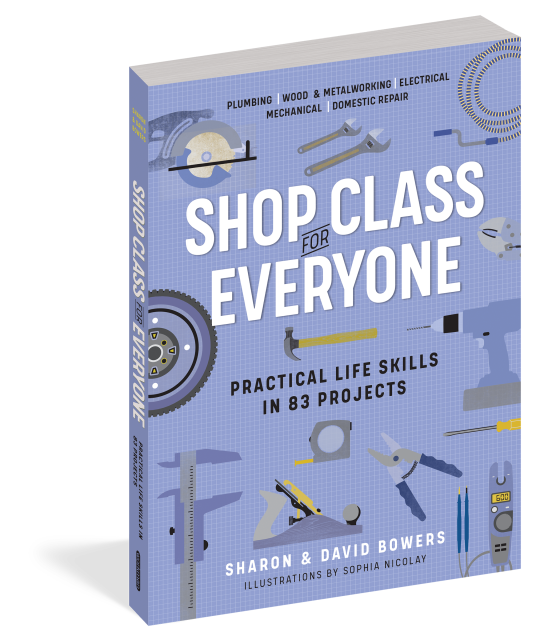

Shop Class for Everyone: Practical Life Skills in 83 Projects

Plumbing · Wood & Metalwork · Electrical · Mechanical · Domestic Repair

Contributors

By David Bowers

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.95Price

$19.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $14.95 $19.95 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Did you remember your goggles?

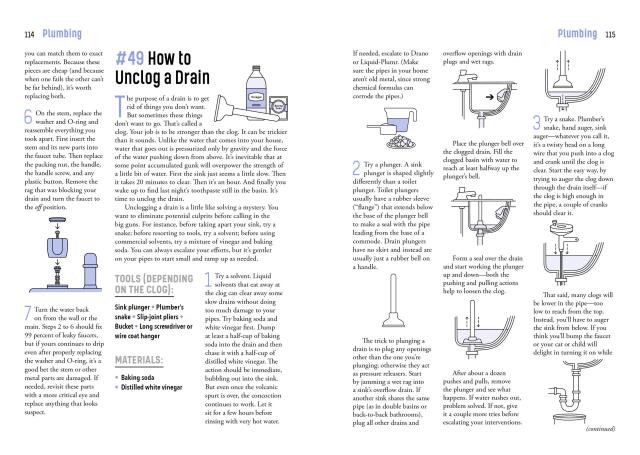

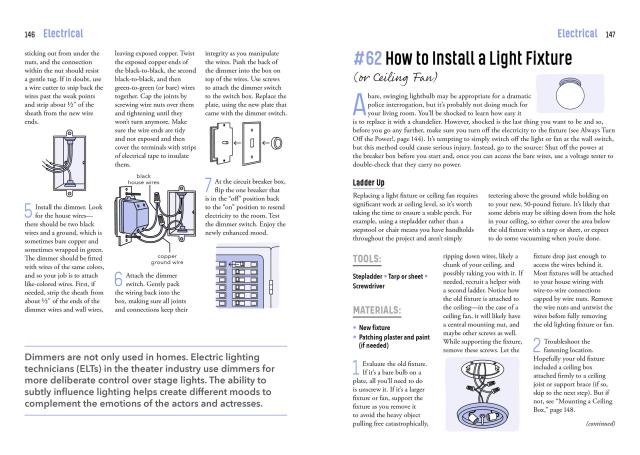

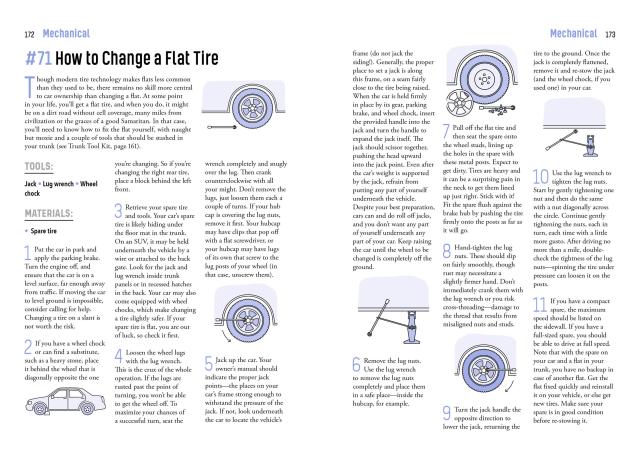

There used to be a time when pretty much every high school offered Shop class, where students learned to use a circular saw or rewire a busted lamp- all while discovering the satisfaction of being self-reliant and doing it yourself. Shop Class for Everyone now offers anyone who might have missed this vital class a crash course in these practical life skills. Packed with illustrated step by step instructions, plus relevant charts, lists, and handy graphics, here’s how to plaster a wall, build a bookcase from scratch, unclog a drain, and change a flat tire (on your car or bike). It’s all made clear in plain, nontechnical language for any level of DIYer, and it comes with a guarantee: No matter how simple the task, doing it with your own two hands provides a feeling of accomplishment that no app or device will ever give you.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2021

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523512386

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use