By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

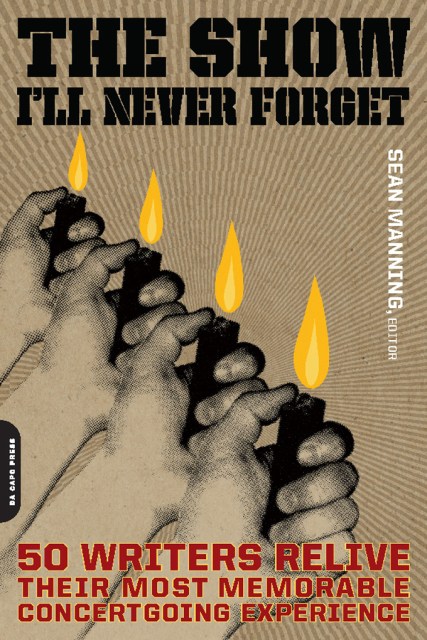

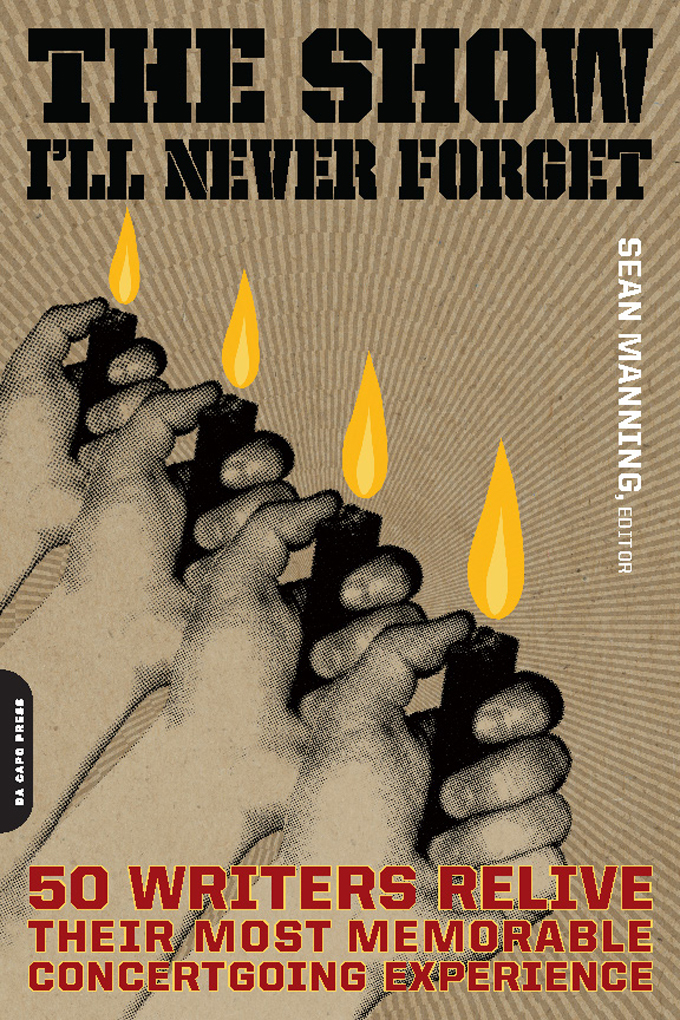

The Show I’ll Never Forget

50 Writers Relive Their Most Memorable Concertgoing Experience

Contributors

By Sean Manning

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 23, 2009

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786734443

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 23, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

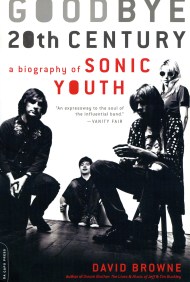

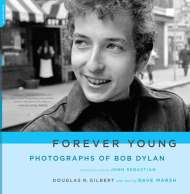

Nick Flynn on Mink DeVille Susan Straight on The Funk Festival Rick Moody on the The Lounge Lizards Jennifer Egan on Patti Smith Harvey Pekar on Joe Maneri Thurston Moore on Glen Branca, Rudolph Grey, and Wharton Tiers Chuck Klosterman on Prince Sigrid Nunez on Woodstock Jerry Stahl on David Bowie Charles R. Cross on Nirvana Marc Nesbitt on The Beastie Boys And many more . . . No matter where your musical taste falls, these often funny, occasionally sad, always thought-provoking essays-all written especially for The Show I’ll Never Forget-are sure to connect with anyone who loves, or has ever loved, live music.

Genre:

-

Paste, 11/13/09

“A simple, genius idea: Get an army of extraordinary writers to dash off remembrances of extraordinary concerts.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use