By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

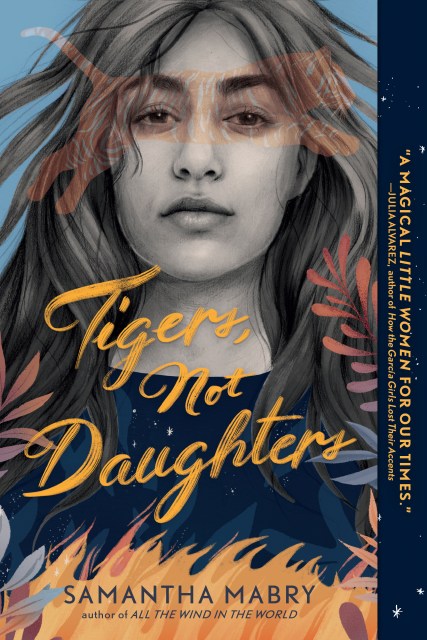

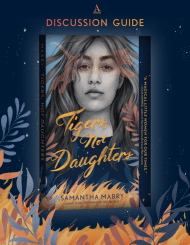

Tigers, Not Daughters

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 30, 2021

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781643751313

Price

$10.95Price

$14.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $10.95 $14.95 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $17.95 $23.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 30, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

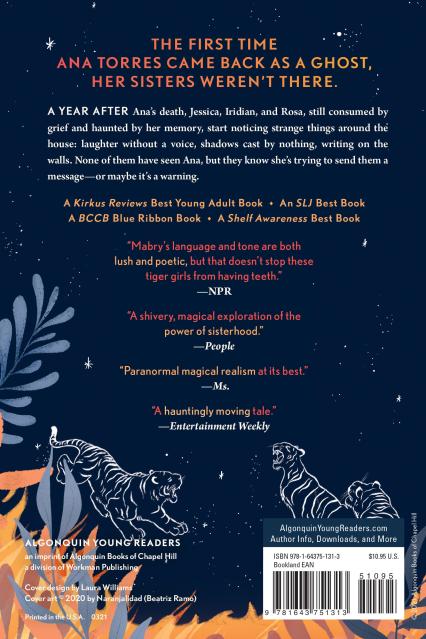

National Book Award nominee Samantha Mabry weaves “a shivery, magical exploration of the power of sisterhood” (People) in this otherworldly Latine ghost story about three sisters shadowed by guilt and grief over the loss of their eldest sister, who haunts their house.

The first time Ana Torres came back as a ghost, her sisters weren’t there.

A year after Ana’s death, Jessica, Iridian, and Rosa, still consumed by grief and haunted by her memory, start noticing strange things around the house: laughter without a voice, shadows cast by nothing, writing on the walls. None of them have seen Ana, but they know she’s trying to send them a message—or maybe it’s a warning.

Tigers, Not Daughters is an aching, lyrical novel with a whisper of magic, that is one part family drama, one part romance, and one part ghost story.

“A moody and unflinching examination of the gritty, tender, and impossible parts of people that make them unforgettably whole. . . Ferocious and gorgeously crafted.” —Courtney Summers, New York Times bestselling author of Sadie

Writers League of Texas Book Award Winner * MPIBA Reading the West Award Winner * Indie Next pick * Kirkus Reviews Best Young Adult Book * SLJ Best Book * Shelf Awareness Best Book * BCCB Blue Ribbon List title * A YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults pick * A White Ravens List pick * NEA Read Across America title * A Must-Read Novel According to BuzzFeed, Entertainment Weekly, Ms. Magazine, BookPage, Publishers Weekly, Tor.com, and D Magazine

And don’t miss Samantha Mabry’s next book: Clever Creatures of the Night!

-

Writers League of Texas Book Award Winner * MPIBA Reading the West Award Winner * Indie Next pick * Kirkus Reviews Best Young Adult Book * SLJ Best Book * Shelf Awareness Best Book * BCCB Blue Ribbon List title * A YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults pick * A White Ravens List pick * NEA Read Across America title * A Must-Read Novel According to BuzzFeed, Entertainment Weekly, Ms. Magazine, BookPage, Publishers Weekly, Tor.com, and D Magazine

-

“A moody and unflinching examination of the gritty, tender and impossible parts of people that make them unforgettably whole. You don't read Samantha Mabry’s books so much as experience them. Ferocious and gorgeously crafted. I loved it.”Courtney Summers, New York Times bestselling author of Sadie

-

* “Mabry speaks gracefully to the transformative power of grief and the often messy (even violent) road to letting go.”Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

* "Borrowing elements of magical realism and Latinx folklore, this is a story that is often uncomfortable; in its quest to explore grief, family, and the traumas inflicted by each, it lays its characters utterly and unforgettably bare.”Booklist, starred review

-

* "A lyrical contemporary YA with a dose of magical realism, Tigers, Not Daughters is an empowering portrait of grief, sisterhood and resilience."Shelf Awareness, starred review

-

* “Mabry's third novel has echoes of The Virgin Suicides . . . The evocative language and deft characterization will haunt—and empower—readers.”Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

* “Little Women meets The Virgin Suicides with a magical realist twist in this evocative and lovely novel . . . An engaging, heartfelt exploration of the multifaceted inner lives of teen girls and sisterhood.”School Library Journal, starred review

-

* "This is quietly searing tale of sisterly love and family secrets, of a grief so big it swallows its mourners up, blotting out the future and distorting the past . . . an appealingly unsettling infusion of ambiguous faith and unexplained miracles.”BCCB, starred review

-

“Move over, Louisa May Alcott! Samantha Mabry has written her very own magical Little Women for our times. This is no family of tamed girls but a clan of fierce and fighting young women who will draw readers into their spell. A celebration of the bonds of sisterhood and of the ways we heal by reaching beyond our losses, our brokenness and fears to the love that holds and heals.”Julia Alvarez, author of How the García Girls Lost Their Accents

-

"Samantha Mabry is just a beautiful writer. You should definitely read it."Veronica Roth, New York Times bestselling author of the Divergent series

-

“The National Book Award-nominated author spins another hauntingly moving tale of teenhood with this story of sisters mourning one of their own, only to realize she might still be walking among them . . . somehow.”Entertainment Weekly

-

"Like Mabry's previous books, I found that Tigers, Not Daughters is all about the atmosphere and feelings. The small town where the Torres sisters dwell feels so real . . . Mabry's language and tone are both lush and poetic, but that doesn't stop these tiger girls from having teeth.”NPR

-

"A shivery, magical exploration of the power of sisterhood.”People

-

"One of the most crucial voices in young adult literature."Bustle

-

"Samantha Mabry gives us paranormal magical realism at its best with her latest YA novel."Ms.

-

“Mabry’s moody writing paints a picture of a grief-stricken family mired in grief and seemingly doom to stay there. The descriptions are sensory, visceral, and weird… The story’s climax is chaotic and cathartic—and it ultimately presents a path forward for the sisters.”Horn Book Magazine

-

"The kind of story that digs its claws deep into you. Though just under 300 pages, Mabry crafts a profoundly character driven plot that explores grief, depression, and sisterhood . . . A powerful story, filled with impactful characters and realistic depictions of grief and depression. Paired with its eerie paranormal elements, Tigers, Not Daughters will haunt your thoughts long after you’ve finished reading.”The Nerd Daily

-

“This fierce, unforgettable whirlwind of a novel, a wondrous mix of ghost story and drama of sisterly rebellion, holds the reader in thrall from the first sentence to the final page.”The Buffalo News

-

"This book is as if you took The Virgin Suicides, mixed it a with Little Women, and weaved it all together with King Lear. Read it, if you are a fan of any of these titles."The Young Folks

-

“Samantha Mabry blends elements of magical realism, moments of connection and grief, and genuinely eerie scares to create a story exploring the ‘magic in small things,’ as well as a timely ode to sisterhood and feminism.”The Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"Mabry is one of our of city’s finest writers.”D Magazine

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use