Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

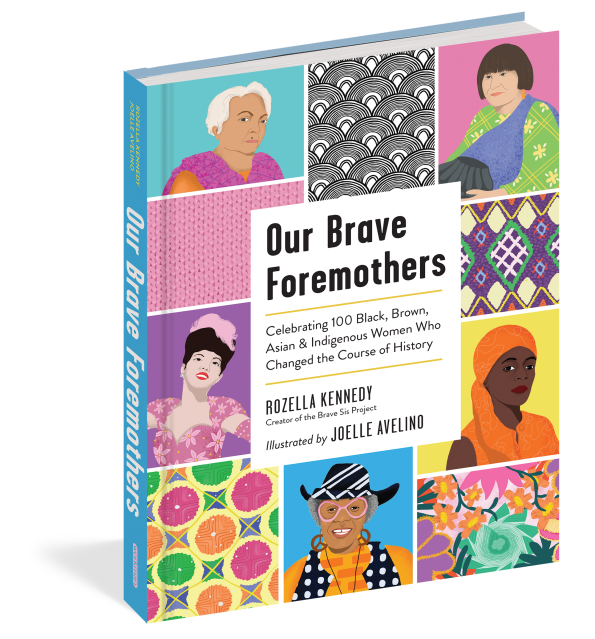

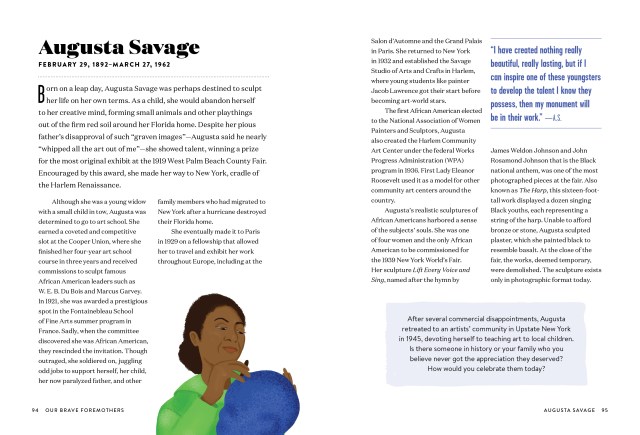

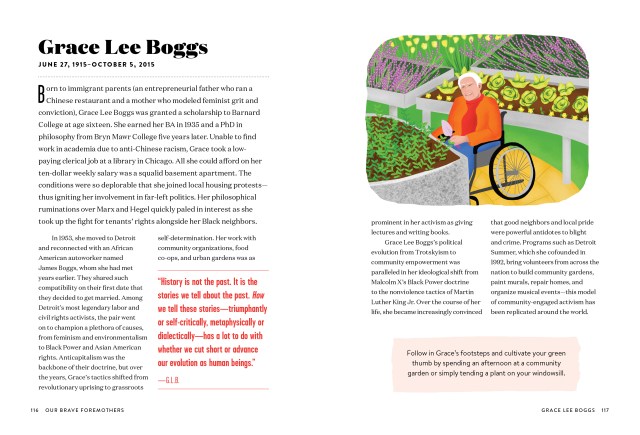

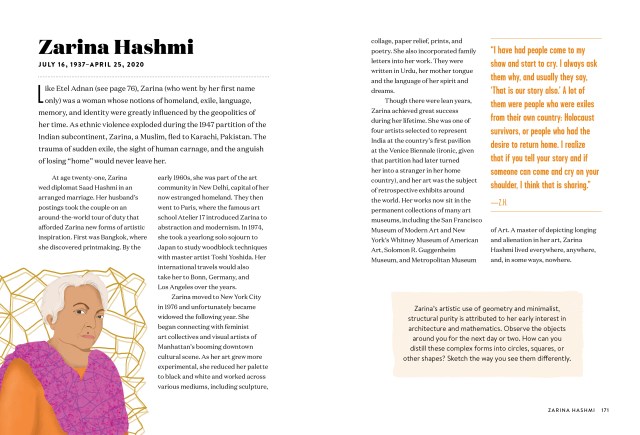

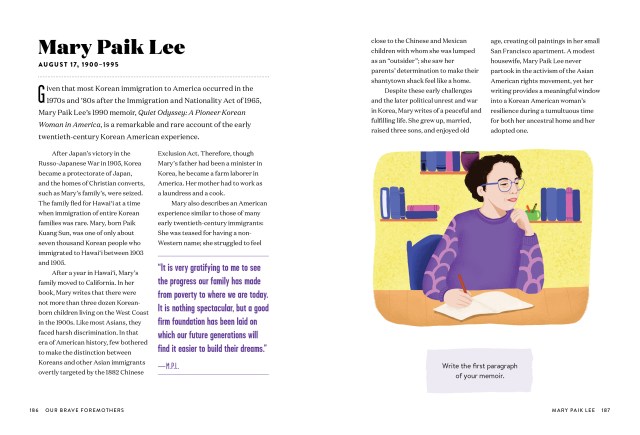

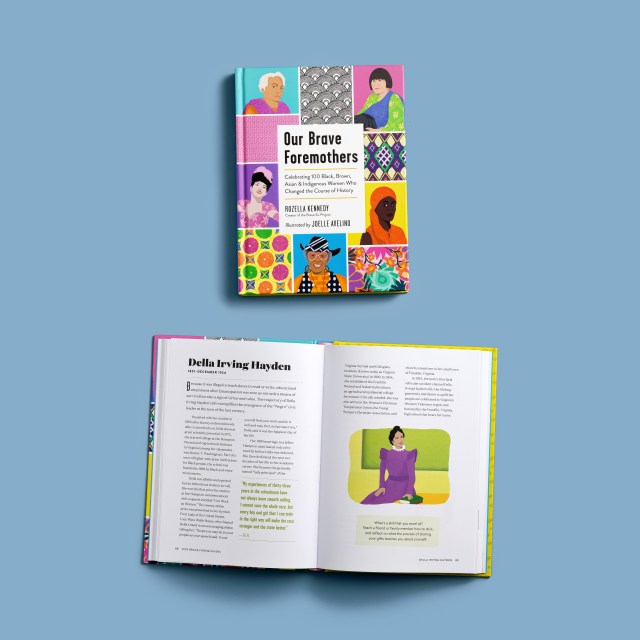

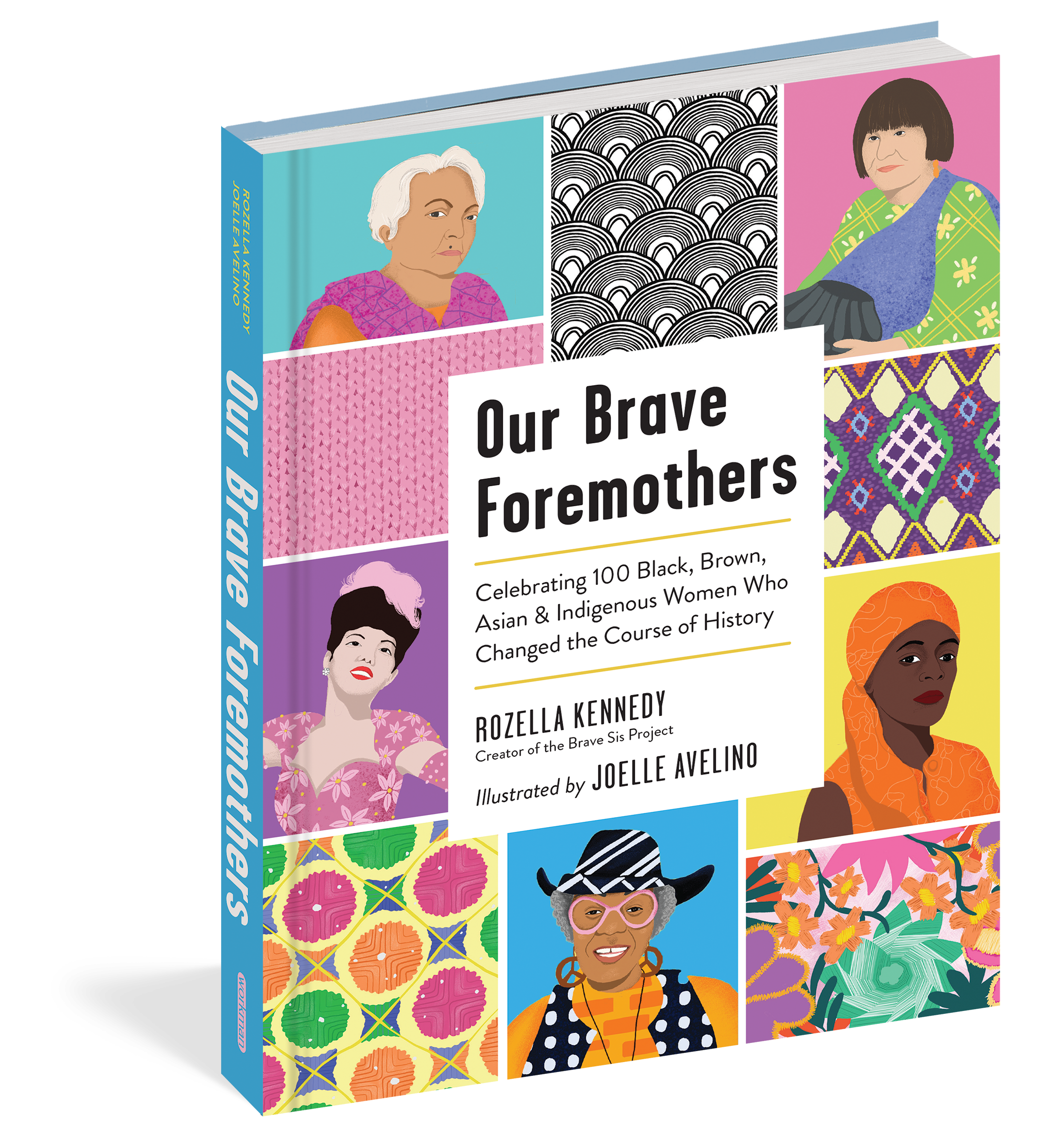

Our Brave Foremothers

Celebrating 100 Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous Women Who Changed the Course of History

Contributors

Illustrated by Joelle Avelino

Formats and Prices

Price

$20.00Price

$26.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $20.00 $26.00 CAD

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 11, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In the beautiful pages of Our Brave Foremothers, discover an intergenerational, intercultural bouquet of Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous women lifted into the significance that they deserve. • From Etel Adnan to Mary Jones, Thelma Garcia Buchholdt to Pura Belpré to Zitkála-Šá, here are 100 women of color who left a lasting mark on United States history. Including both famous and little-known names, the thoughtful profiles and detailed portraits of these women herald their achievements and passions. • Following each entry is a prompt that asks you to connect your life to theirs, an inspiring way to understand their influence and the power of their stories. To consider on a deeper level the devotedness of Clara Brown, the fearlessness of Jovita Idár, the guts of Grace Lee Boggs, or the selflessness of Martha Louise Morrow Foxx. And to be as brave as we each can be—and then beyond that.

Genre:

-

"Kennedy compiles short, eminently readable biographies of one-hundred Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous women in this interactive book…Activists, artists, athletes, and scientists all receive long overdue recognition in this attractive volume that is well-suited for public library and circulating reference collections. This engaging illustrated volume is well-suited to young scholars.” —Booklist

“At a time when women’s history is being lifted up, this accessible work will edify casual and academic readers and may be used as a reference for some.” —Library Journal

“An essential book that connects us to our past and current sisters and reminds us that each of our stories matters.” —Ruth Chan, illustrator and author

“A long overdue portrayal of inspiring hidden figures whose stories needed to be told to the world.” —Rokhaya Diallo, journalist, writer, and award-winning filmmaker

“Our Brave Foremothers sheds truth on old perceptions and gives us stories both informative and inspiring about women who paved the way for generations of women to follow.” —Audrey Edwards, former executive editor of Essence magazine and author of American Runaway: Black and Free in Paris in the Trump Years

“Our Brave Foremothers is the book that every family should have on their coffee table. It’s a visual encyclopedia of greatness for our future generation to know about the work done by these important women.” —Joy Cho, author and founder of Oh Joy!

- On Sale

- Apr 11, 2023

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9781523514557

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use