Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

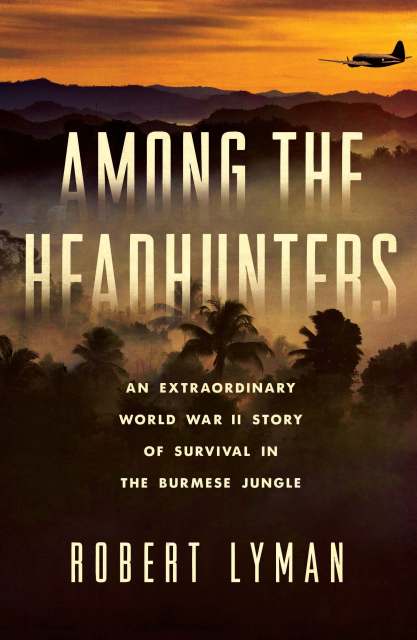

Among the Headhunters

An Extraordinary World War II Story of Survival in the Burmese Jungle

Contributors

By Robert Lyman

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $17.99 $22.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 7, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Flying the notorious “Hump” route between India and China in 1943, a twin-engine plane suffered mechanical failure and crashed in a dense mountain jungle, deep within Japanese-held territory. Among the passengers and crew were celebrated CBS journalist Eric Sevareid, an OSS operative who was also a Soviet double agent, and General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell’s personal political adviser. Against the odds, all but one of the twenty-one people aboard the doomed aircraft survived-it remains the largest civilian evacuation of an aircraft by parachute. But they fell from the frying pan into the fire.

Disentangling themselves from their parachutes, the shocked survivors discovered that they had arrived in wild country dominated by a tribe with a special reason to hate white men. The Nagas were notorious headhunters who routinely practiced slavery and human sacrifice, their specialty being the removal of enemy heads. Japanese soldiers lay close by, too, with their own brand of hatred for Americans.

Among the Headhunters tells-for the first time-the incredible true story of the adventures of these men among the Naga warriors, their sustenance from the air by the USAAF, and their ultimate rescue. It is also a story of two very different worlds colliding-young Americans, exuberant apostles of their country’s vast industrial democracy, coming face-to-face with the Naga, an ancient tribe determined to preserve its local power based on headhunting and slaving.

Disentangling themselves from their parachutes, the shocked survivors discovered that they had arrived in wild country dominated by a tribe with a special reason to hate white men. The Nagas were notorious headhunters who routinely practiced slavery and human sacrifice, their specialty being the removal of enemy heads. Japanese soldiers lay close by, too, with their own brand of hatred for Americans.

Among the Headhunters tells-for the first time-the incredible true story of the adventures of these men among the Naga warriors, their sustenance from the air by the USAAF, and their ultimate rescue. It is also a story of two very different worlds colliding-young Americans, exuberant apostles of their country’s vast industrial democracy, coming face-to-face with the Naga, an ancient tribe determined to preserve its local power based on headhunting and slaving.

Genre:

-

Praise for Among the Headhunters

"This is an extraordinary story of the sudden confrontation of two civilizations on the edge of the British Empire which ended in harmony and affection. It is excellently told, exciting, vivid, and moving."—Alan MacFarlane, author of Riddle of the Modern World, The Savage Wars of Peace, and Empire of Tea

"A wonderfully gripping and life-affirming story of a little-known episode of World War II. Robert Lyman's deep understanding of and affection for the extraordinary Naga people and their beautiful forgotten corner of the world infuses this compelling tale of triumph over adversity and of an unlikely friendship between very different people and characters suddenly and unexpectedly thrown together. Beautifully written and researched, it is both highly relevant and a testimony to the power of the human spirit."—James Holland, author of The Rise of Germany, 1939-1941

"Robert Lyman brings the skills of a born storyteller and the erudition of an historian to this wonderful book. His long engagement with and affection for the people of the Burmese jungle shine through. It is a gripping and immensely humane book."—Fergal Kane, author of Season of Blood and Road of Bones

South China Morning Post, 6/20/2016

“[An] amazing true story of wartime grit in Burma.”

-

"[Robert Lyman's] expertise shows through in the book's smooth prose and clear storytelling."WWII History

- On Sale

- Jun 7, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306824685

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use