By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

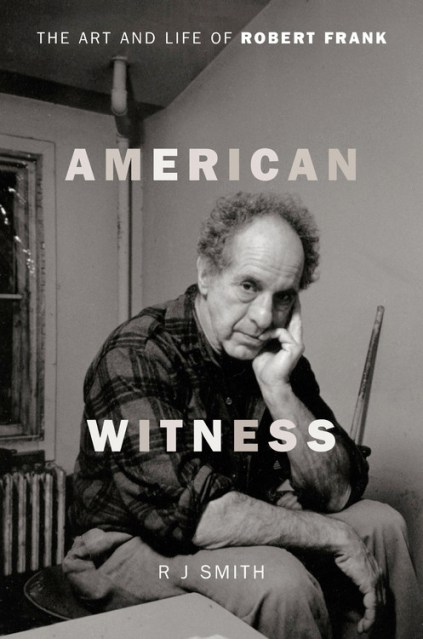

American Witness

The Art and Life of Robert Frank

Contributors

By RJ Smith

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306823367

Price

$35.00Price

$45.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.50 CAD

- ebook $23.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As well-known as Robert Frank the photographer is, few can say they really know Robert Frank the man. Born and raised in wartime Switzerland, Frank discovered the power and allure of photography at an early age and quickly learned that the art meant significantly more to him than the money, success, or fame. The art was all, and he intended to spend a lifetime pursuing it.

American Witness is the first comprehensive look at the life of a man who’s as mysterious and evasive as he is prolific and gifted. Leaving his rigid Switzerland for the more fluid United States in 1947, Frank found himself at the red-hot social center of bohemian New York in the ’50s and ’60s, becoming friends with everyone from Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and Peter Orlovsky to photographer Walker Evans, actor Zero Mostel, painter Willem de Kooning, filmmaker Jonas Mekas, Bob Dylan, writer Rudy Wirlitzer, jazz musicians Ornette Coleman and Charles Mingus, and more. Frank roamed the country with his young family, taking roughly 27,000 photographs and collecting 83 of them into what is still his most famous work: The Americans. His was an America nobody had seen before, and if it was harshly criticized upon publication for its portrait of a divided country, the collection gradually grew to be recognized as a transformative American vision.

And then he turned his back on certain success, giving up photography to reinvent himself as a film and video maker. Frank helped found the American independent cinema of the 1960s and made a legendary film with the Rolling Stones. Today, the nonagenarian is an embodiment of restless creativity and a symbol of what it costs to remain original in America, his life defined by never repeating himself, never being satisfied. American Witness is a portrait of a singular artist and the country that he saw.

-

"Sprinkled with subtle touches of poetic discourse and [Smith's] deeply felt passion and admiration for Frank's work, this book is a page-turning emotional delight."Kirkus

-

"A comprehensive biography...Smith deliver[s] a multidimensional portrait of a man best known for depicting others."Booklist

-

"Well-observed."Esquire

-

"One of [Smith's] most interesting books, by far."Buffalo News

-

"An absorbing study of an enigmatic but engaging artist who still has much to say."Library Journal

-

"American Witness anecdotally demonstrates Frank's far reaching influence. Smith's skills as a storyteller make this an engaging journey."PopMatters

-

"American Witness is a definitive portrait of a singular artist and the country that he saw, making it unreservedly recommended."Midwest Book Review

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use