By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

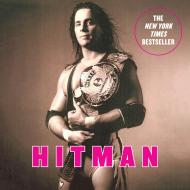

Rise

Surviving the Fight of My Life

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 10, 2018

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Legacy Lit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316472272

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 10, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As a young girl growing up in Newberg, Oregon, Paige Sletten was all energy and full of potential. A natural athlete, Paige excelled at dancing, made the cheerleading squad earlier than most, and even had aspirations of becoming a Disney child star. With a tight-knit family, Paige’s life was on track for greatness. Then, one fateful fall night in high school, everything changed when Paige faced a life-threatening sexual assault. It was in the gym where she “pounded the life out of those ashen memories,” becoming stronger with every punch, kick, and lunge. In this beautiful tale of survival, she writes:

I inhale the power.

I exhale the bullshit.

One strike at a time.

Fighting became Paige’s safe haven; something to live for, and Rise is the inspiring story of how she ultimately transformed into a bone-breaking, head-smashing fighter known as Paige VanZant. It is the deeply moving story of a warrior who transformed her pain into power and has become one of the toughest women in the world; an inspiring journey of someone who was knocked down in the most devastating way and came up swinging.

-

"MMA fighter Paige VanZant had to defeat obstacles in and out of the Octagon."ESPN.com

-

"[A] book about surviving the face of evil."MMA Mania

-

"Paige VanZant is some warrior....the journey VanZant has had to endure before reaching the bright lights of the UFC is what makes her truly remarkable....VanZant conveys the fear, anxiety, and hopelessness that consumed her during those years with such stirring honesty.... [Rise] provides other[s] vital hope that recovery and survival can be achieved. Paige VanZant is a hero and an inspiration. Her story of remarkable courage and survival needs to be read."TheSportsBookClub.com

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use