Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

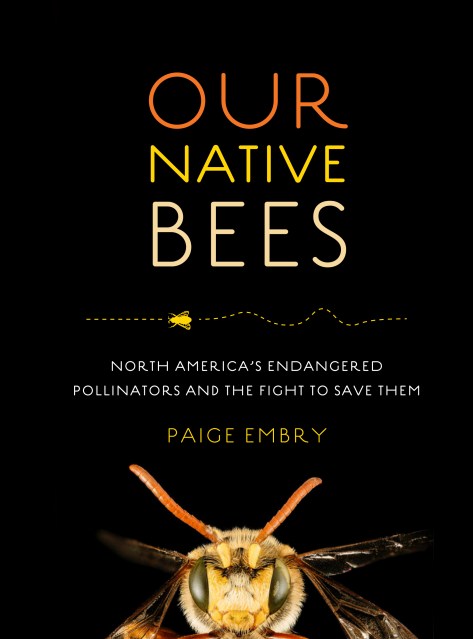

Our Native Bees

North America's Endangered Pollinators and the Fight to Save Them

Contributors

By Paige Embry

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.95 $32.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 7, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A New York Times 2018 Holiday Gift Selection

Honey bees get all the press, but the fascinating story of North America’s native bees—endangered species essential to our ecosystems and food supplies—is just as crucial. Through interviews with farmers, gardeners, scientists, and bee experts, Our Native Bees explores the importance of native bees and focuses on why they play a key role in gardening and agriculture. The people and stories are compelling: Paige Embry goes on a bee hunt with the world expert on the likely extinct Franklin’s bumble bee, raises blue orchard bees in her refrigerator, and learns about an organization that turns the out-of-play areas in golf courses into pollinator habitats. Our Native Bees is a fascinating, must-read for fans of natural history and science and anyone curious about bees.

Honey bees get all the press, but the fascinating story of North America’s native bees—endangered species essential to our ecosystems and food supplies—is just as crucial. Through interviews with farmers, gardeners, scientists, and bee experts, Our Native Bees explores the importance of native bees and focuses on why they play a key role in gardening and agriculture. The people and stories are compelling: Paige Embry goes on a bee hunt with the world expert on the likely extinct Franklin’s bumble bee, raises blue orchard bees in her refrigerator, and learns about an organization that turns the out-of-play areas in golf courses into pollinator habitats. Our Native Bees is a fascinating, must-read for fans of natural history and science and anyone curious about bees.

Genre:

-

“Designed to educate everyone from bee and honey enthusiasts to amateur gardeners and agricultural professionals, Embry’s captivating profiles of just a few of the myriad native bee species and the dedicated individuals and institutions committed to their survival are as entertaining as they are enlightening.” —Booklist

“Guides us through the world of overlooked and obscure bee species that fill the air around us: bumblebees, masons, alkali, leaf cutters, diggers, miners and many more.” —The Wall Street Journal

“Clear and crisp. . . . A flight path through overwhelming amounts of information.” —New York Times Book Review

“Embry—an independent scholar—shares her enthusiasm and concerns for these lesser-known but important insect pollinators. . . . Embry writes in an easygoing, conversational style. Nicely illustrated with a variety of full-color photographs, this book is an enjoyable read, suitable for both bee enthusiasts and general interest readers.” —Choice starred review

“A buzzworthy book if ever there was one.” —Country Gardens

“A wide ranging, entertaining survey.” —Food Tank

“The readability of this book to non-scientists . . . is due to her passionate interest in bees.” —Triangle Gardener

“With vivid color photography, thorough research and humor (such as her children’s horror when they discover bees in the refrigerator), you’ll come away laughing, better informed and ready to heed her clarion call to save these indispensable insects.” —Seattle Magazine

“Embry artfully weaves together descriptions of native bees with accounts of the state of the science from leading research programs. . . . This book will open readers’ eyes to the great diversity and importance of these creatures, and what’s being done to learn all about their biology. . . Embry has found a calling as an ambassador for all the “other” bees, and she is inspiring audiences to care about these insects while they are still here to be cared for.” —American Entomologist

“Embry writes with passion, humor, and authority, and this book carries an important message—that we need to care for these little creatures that quietly pollinate our crops.” —Dave Goulson, author of A Sting in the Tale

“An absolute must-read. Embry takes us along on her engaging journey of discovery as she learns about the incredible diversity of our native bees and how they live.” —Stephen Buchmann, author of The Forgotten Pollinators and The Reason for Flowers

“Embry’s book is witty, insightful, and full of valuable information for both the long-time lover of bees and those just-now curious. She captures the essence of a bee’s natural history and how we use (and sometimes abuse) bees.” —Olivia Messinger Carril, author of The Bees in Your Backyard: A Guide to North America’s Bees

“Embry’s writing is fresh and funny, and her enthusiasm for her subject contagious.” —The Maine Organic Farm Gardener

“A very compelling book.” —Appalachian Voices

“Embry possesses a voracious curiosity, a genuine interest in people and nature, and an ability to digest science and the people who practice it into illuminating and humorous stories. . . . Our Native Bees is essential reading.” —Story Circle Book Reviews

“Embry’s writing style is superbly suited to her task. Her friendly, humor-filled prose. . . makes the book particularly inviting to newcomers to the subject.” —The Well-Read Naturalist

“A charming narrator. . . . Our Native Bees is a keeper for people interested in our food supply—gardeners in particular—as it relates to bees. The book is also essential for those of us who enjoy good writing with a bent toward natural history and science, who are simply keen to know more about the world around us.” —The Missoulian

“The narrative comes alive with photographs that beautifully render her subjects, tiny or robust, hirsute or sleek, jewel-like or armored.” —Quarterly Review of Biology

“Friendly, humor-filled prose… clear and down-to-earth explanations of the ecological role these different species play, as well as a collection truly remarkable macro images that vividly depict just how diverse and beautiful they are.” —TheWell Read Naturalist

“This book is as fun to read as it is a collection of stories. It is the story of bees told through the people who depend on them.” —The Albany Herald

“In an entertaining account of her personal bee adventures (far more fascinating than I had anticipated), Embry’s book sets the record straight about the immense value and the precarious future of our native bees… I enjoyed every page of our native bees.” —Seeds

“Fascinating…punctuated by beautiful, up-close photos of bees, and the author’s passion and friendly tone.” —Newsday

- On Sale

- Feb 7, 2018

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604698411

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use