Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

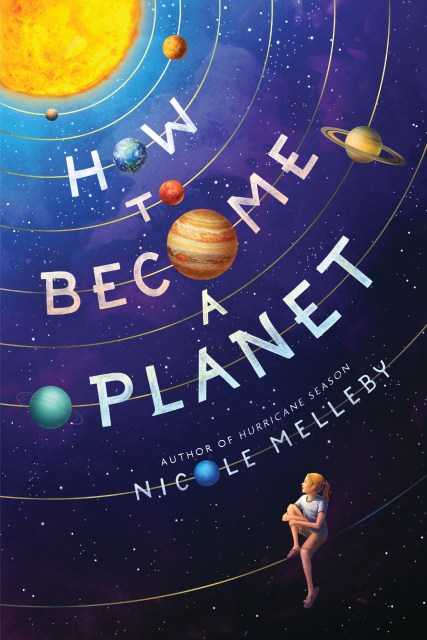

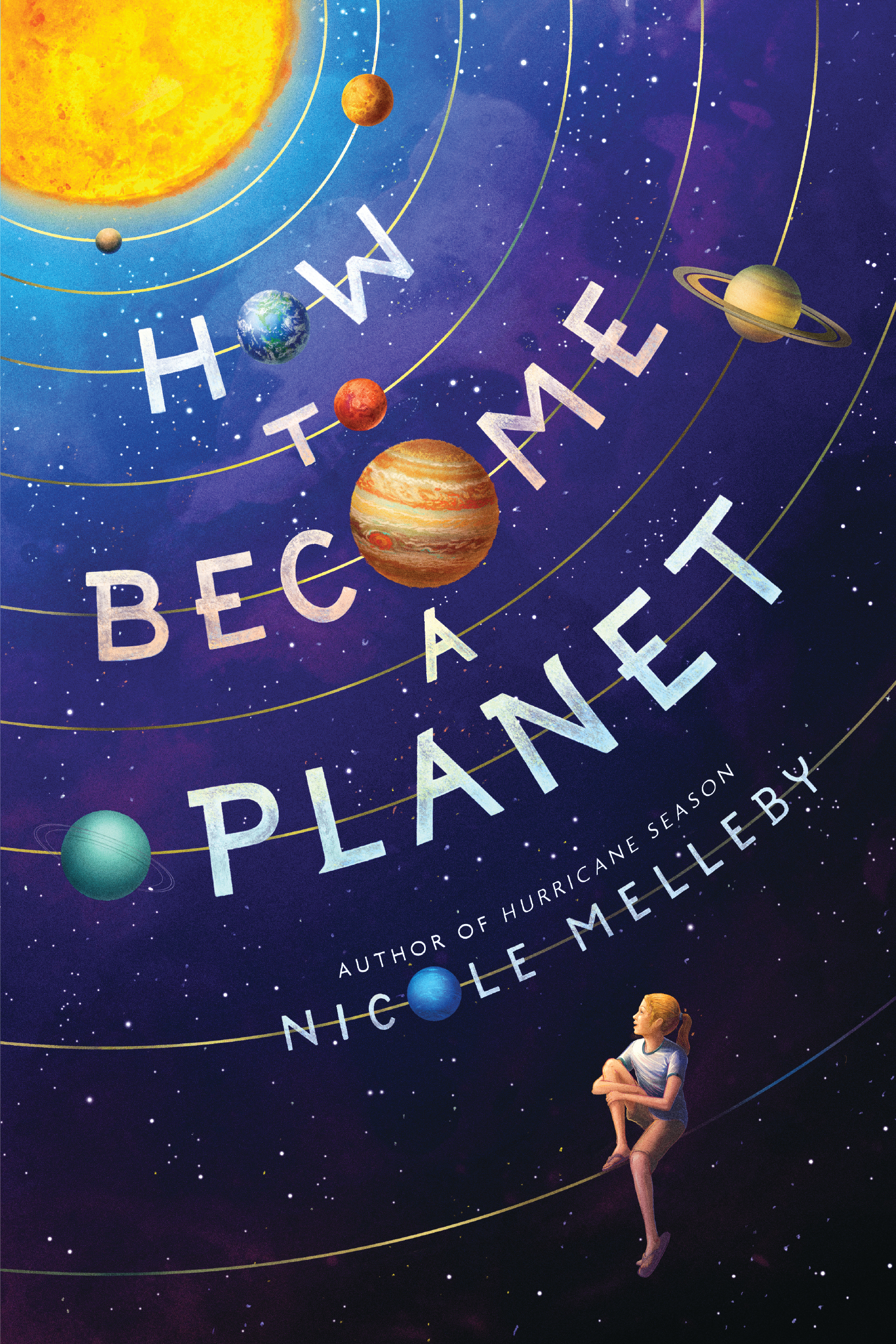

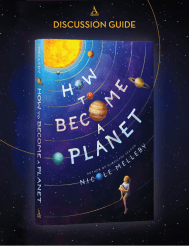

How to Become a Planet

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- ebook $6.99 $8.99 CAD

- Hardcover $16.95 $22.95 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 19, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A Publishers Weekly Best Middle Grade Book of 2021

One of The Nerd Daily's “Anticipated Queer Book Releases You Can’t Miss in 2021”

One of Lambda Literary's “May’s Most Anticipated LGBTQ Literature”

“Gorgeous.” —BuzzFeed

The two most important things to know about Pluto Timoney: (1) she’s always loved outer space (obviously); and (2) her favorite season is summer, the time to go to the boardwalk, visit the planetarium, and work in her mom’s pizzeria.

This summer, when Pluto’s turning thirteen, is different. Pluto has just been diagnosed with depression, and she feels like a black hole is sitting on her chest, making it hard to do anything. When Pluto’s dad threatens to make her move to the city—where he believes his money could help her get better—Pluto comes up with a plan to do whatever it takes to be her old self again. If she does everything that old, “normal” Pluto would do, she can stay with her mom. But it takes a new therapist, new tutor, and new (cute) friend with a plan of her own for Pluto to see that there is no old or new her. There’s just Pluto, discovering more about herself every day.

Genre:

-

A Publishers Weekly Best Middle Grade Book of 2021

One of The Nerd Daily's “Anticipated Queer Book Releases You Can’t Miss in 2021”

One of Lambda Literary's “May’s Most Anticipated LGBTQ Literature”

“As always, Melleby naturally integrates her queer protagonist’s discovery of her sexuality into a larger story. The love of space that Pluto shares with her mother (whose own stress level is honestly portrayed) informs her way of thinking about herself and the world; Pluto’s interest in the history of the Challenger disaster is just one reason this introspective novel might appeal to fans of Erin Entrada Kelly’s We Dream of Space.”

—The Horn Book Magazine

“Nicole Melleby, author of "In the Role of Brie Hutchins," offers a sensitive, pitch-perfect portrayal of a girl battling depression and anxiety disorder the summer before 8th grade in this excellent novel for middle-grade readers. … This is an important and ultimately hopeful book.”

—The Buffalo News

“An outstanding book.”

—The City Book Review, Kid’s Book Buzz

“Sprinkled with astronomy-related metaphors related to a planet’s properties, this acutely observed, authentically told tale by Melleby (In the Role of Brie Hutchens...) thoughtfully portrays Pluto’s relationship with her worried single mother, the girl’s urgent desire to 'be fixed,' and her intense—and at times overpowering—depressive episodes. Compassionate secondary characters and a strong sense of place further buoy the narrative.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“A raw yet honest portrayal of a young person’s experience with depression, this is a must-read for both middle grade readers and the teachers, counselors, parents, and other adults who interact daily with youth undergoing similar experiences.”

—School Library Journal, starred review

“Lambda Literary Awards finalist Melleby tackles the gravitational force of the youth mental health crisis . . . Readers will find insight and compassion around setting realistic goals and navigating results that may not match initial expectations . . . A realistic, hopeful account of personal recovery and discovery.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Pluto's struggles to manage her depression are all very true to life, and Melleby handles the subject with respect and empathy. She extends that empathetic tone to the people in Pluto's orbit, who want to help but don't always know how, especially when their well-meaning attempts have unintended consequences. A character-driven novel with a hopeful tone that will resonate with many tweens.”

—Booklist

“The visceral details of the struggle to get out of bed, shower, and greet the day offer insight into the sheer weight of Pluto’s depression, and the frustrated efforts of family and friends to help, help, and keep helping are also compassionately portrayed.”

—The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

“Nuanced and honest to a fault, How to Become a Planet is an inspiring and educative story about how mental illness affects children and how peer and family acceptance can go a long way in fighting the isolation self-stigma often engenders.”

—The Nerd Daily

“Both empowering and comforting, How to Become a Planet will break your heart and infuse it with hope all at once. A beautiful, essential read.”

—Ashley Herring Blake, author of the Stonewall Honor book, Ivy Aberdeen’s Letter to the World

“How do you solve a problem, when it feels like the problem is you? Sensitive, authentic, and expertly crafted, How to Become a Planet rockets readers on a young girl's wavering journey toward self-acceptance and recovery. Pluto's story pummels the heart, leaving it aching and tender—yet, like its hero, stronger as well.”

—Lisa Jenn Bigelow, author of the Lambda Literary Award book, Hazel's Theory of Evolution

“Melleby takes a sensitive and nuanced approach to portraying mental illness in How to Become a Planet. I loved getting pulled into the orbit of Pluto's life as she navigates diagnoses of depression and anxiety, changing relationships with her mom and classmates, and her first crush over the course of one summer. An accessible, inclusive, and beautifully hopeful story.”

—A.J. Sass, author of Ana on the Edge

- On Sale

- Apr 19, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781643752617

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use