By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

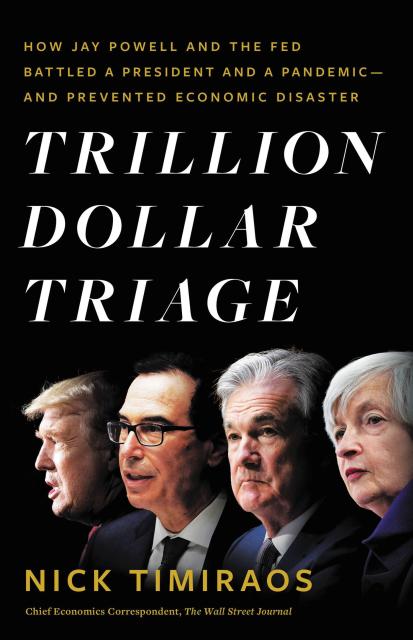

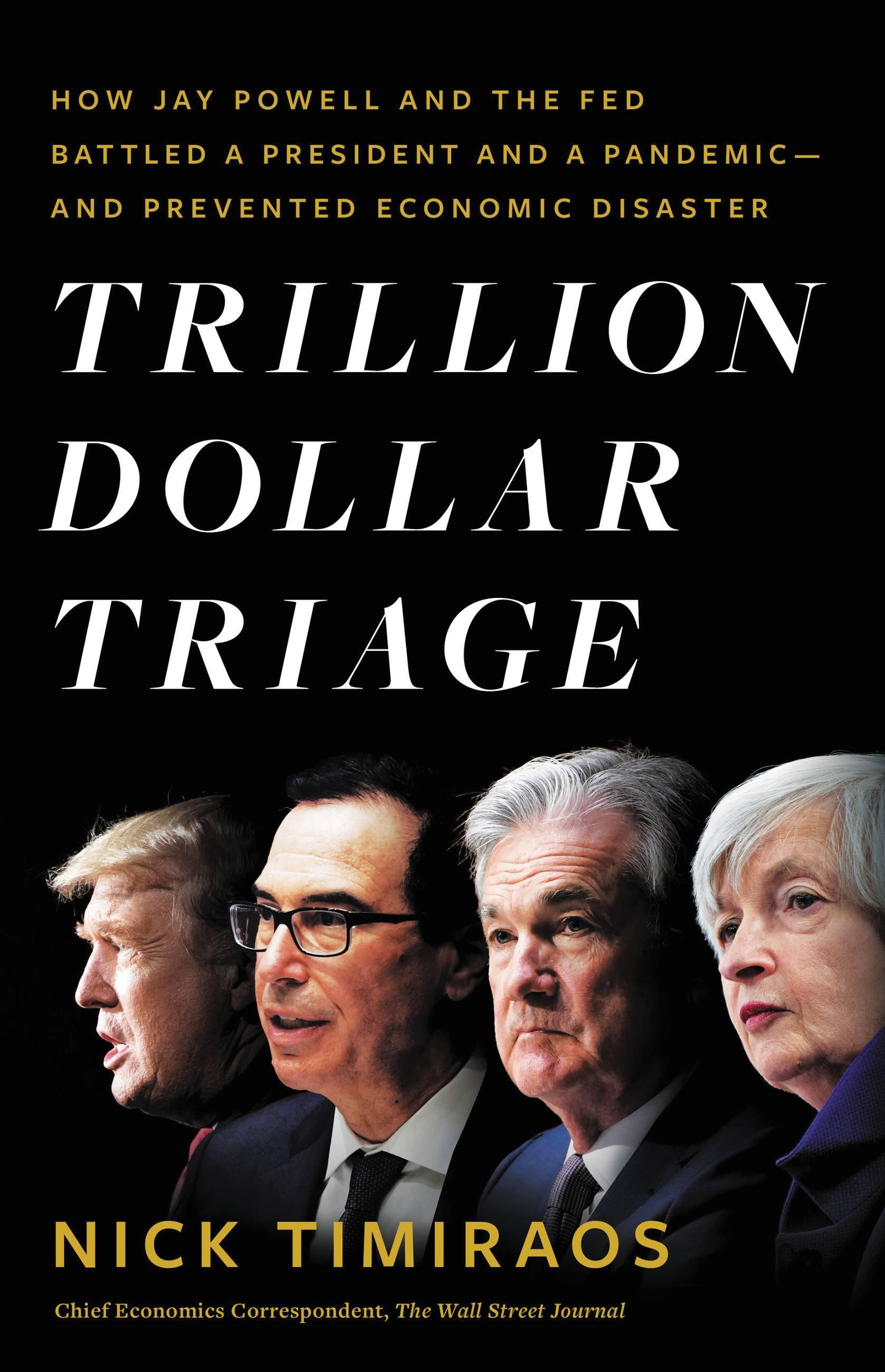

Trillion Dollar Triage

How Jay Powell and the Fed Battled a President and a Pandemic---and Prevented Economic Disaster

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 1, 2022

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316273077

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 1, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The inside story, told with “insight, perspective, and stellar reporting,” of how an unassuming civil servant created trillions of dollars from thin air, combatted a public health crisis, and saved the American economy from a second Great Depression (Alan S. Blinder, former Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve).

By February 2020, the U.S. economic expansion had become the longest on record. Unemployment was plumbing half-century lows. Stock markets soared to new highs. One month later, the public health battle against a deadly virus had pushed the economy into the equivalent of a medically induced coma. America’s workplaces—offices, shops, malls, and factories—shuttered. Many of the nation’s largest employers and tens of thousands of small businesses faced ruin. Over 22 million American jobs were lost. The extreme uncertainty led to some of the largest daily drops ever in the stock market.

Nick Timiraos, the Wall Street Journal’s chief economics correspondent, draws on extensive interviews to detail the tense meetings, late night phone calls, and crucial video conferences behind the largest, swiftest U.S. economic policy response since World War II. Trillion Dollar Triage goes inside the Federal Reserve, one of the country’s most important and least understood institutions, to chronicle how its plainspoken chairman, Jay Powell, unleashed an unprecedented monetary barrage to keep the economy on life support. With the bleeding stemmed, the Fed faced a new challenge: How to nurture a recovery without unleashing an inflation-fueling, bubble-blowing money bomb?

Trillion Dollar Triage is the definitive, gripping history of a creative and unprecedented battle to shield the American economy from the twin threats of a public health disaster and economic crisis. Economic theory and policy will never be the same.

-

“This is the book we need. The Federal Reserve’s actions since the pandemic hit have been numerous, varied, huge—and poorly understood. Nick Timiraos straightens it all out with insight, perspective, and stellar reporting. Thank you, Nick.”Alan S. Blinder, Professor of Economics at Princeton University and former Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve

-

“Nick Timiraos takes readers behind the curtain to see how the creativity and courage of leaders—in this case Jay Powell and his ‘troika plus one’—could save a terrified nation from falling into an economic abyss. In the midst of a health crisis and political and economic turmoil, we were lucky to have that leadership, as we are now to have this gripping narrative.”Jacob J. Lew, former U.S. Treasury Secretary

-

“As the Fed, again, rushes to rescue the economy, Nick Timiraos goes backstage to reveal what Jay Powell and his colleagues were doing, thinking, and worrying about and why. It’s all here: the history, the economics, the politics, the tensions between key actors, the revealing interviews, the previously unreported details – all meticulously reported and deftly told.”David Wessel, Author of In Fed We Trust: Ben Bernanke’s War on the Great Panic and Director of Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy, Brookings Institution

-

“The economy collapsed from the pandemic but the Great Financial Crisis of 2020 never happened. Nick Timiraos helps us understand why with a front row seat on the decisions made by Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve. But whether it’s the Fed’s unprecedented moves, President Trump’s public attacks of the Chair, or Congress pulling the Fed directly into fiscal policy, the book raises the haunting, crucial question of whether things will ever be the same again.”Austan D. Goolsbee, former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers and Robert P. Gwinn Professor of Economics at University of Chicago Booth School of Business

-

"detailed, original reporting...fast-paced...[Trillion Dollar Triage] makes clear how much of a collective process this dizzying month of policymaking was...the pages about the current battle against inflation read like a rough draft of a history that is still being written. Powell’s legacy and the credibility of the Fed will be influenced by how this story turns out. For answers, we may have to wait for Timiraos to write a sequel."Jason Furman, The Washington Post

-

“This is a riveting story of policy making in crisis and an illuminating examination of how drastically the Fed’s role in the economy has changed.”Publishers Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use