Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

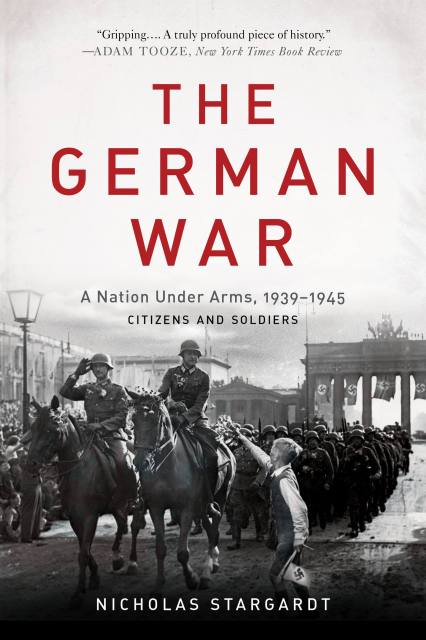

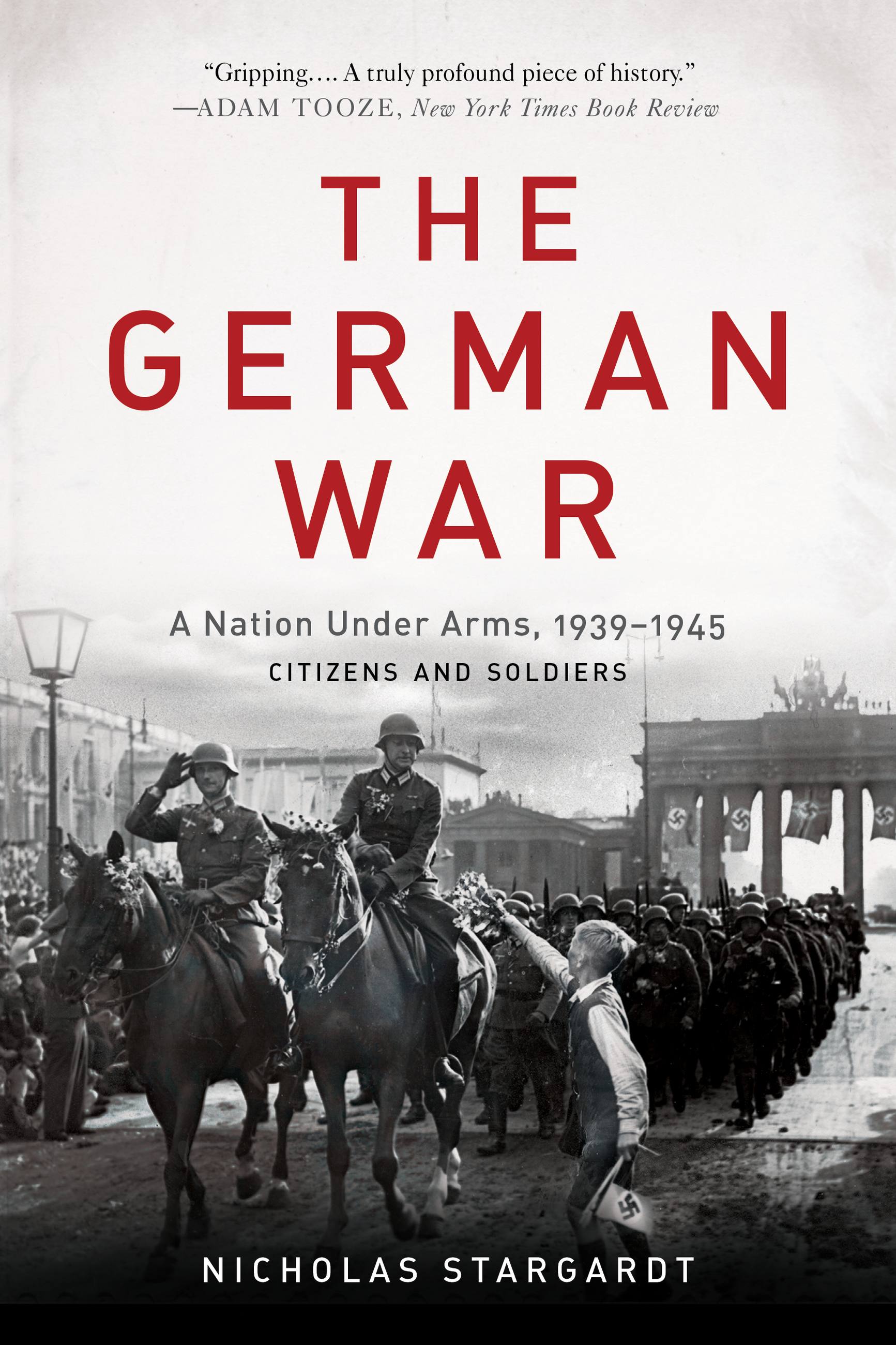

The German War

A Nation Under Arms, 1939-1945

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 13, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A groundbreaking history of what drove the Germans to fight — and keep fighting — for a lost cause in World War II

In The German War, acclaimed historian Nicholas Stargardt draws on an extraordinary range of firsthand testimony — personal diaries, court records, and military correspondence — to explore how the German people experienced the Second World War.

When war broke out in September 1939, it was deeply unpopular in Germany. Yet without the active participation and commitment of the German people, it could not have continued for almost six years. What, then, was the war the Germans thought they were fighting? How did the changing course of the conflict — the victories of the Blitzkrieg, the first defeats in the east, the bombing of German cities — alter their views and expectations? And when did Germans first realize they were fighting a genocidal war?

Told from the perspective of those who lived through it — soldiers, schoolteachers, and housewives; Nazis, Christians, and Jews — this masterful historical narrative sheds fresh and disturbing light on the beliefs and fears of a people who embarked on and fought to the end a brutal war of conquest and genocide.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 13, 2015

- Page Count

- 760 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465073979

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use