Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

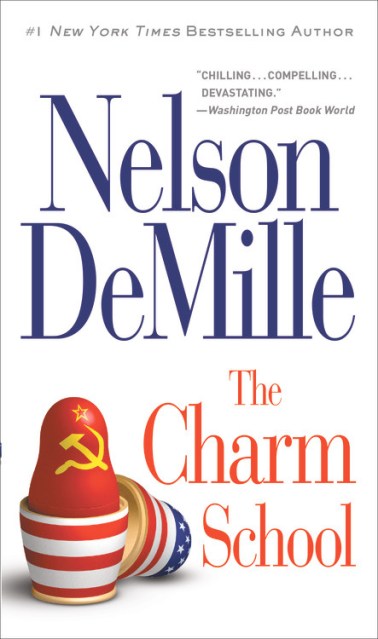

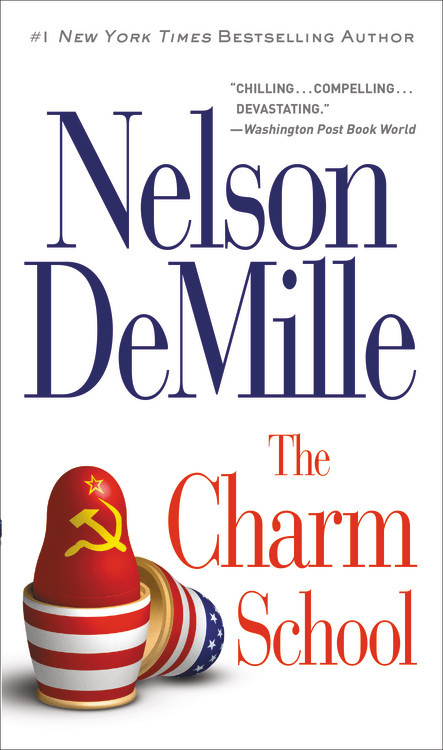

The Charm School

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Mass Market $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Hardcover $34.00 $44.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 25, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On a dark road deep inside the Russian woods at Borodino, a young American tourist picks up an unusual passenger with an explosive secret: an U.S. POW on the run from “The Charm School,” a sinister operation where American POWs teach young KBG agents how to be model U.S. citizens. Their goal? To infiltrate the United States undetected. With this horrifying conspiracy revealed, the CIA sets an investigation in motion, and three Americans–an Air Force officer, an embassy liaison, a CIA chief–pit themselves against the country’s enemies in a high-powered game of international intrigue.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 25, 2017

- Page Count

- 800 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538744277

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use