Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

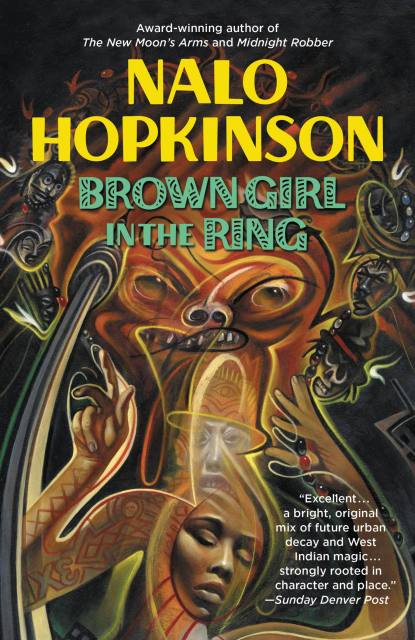

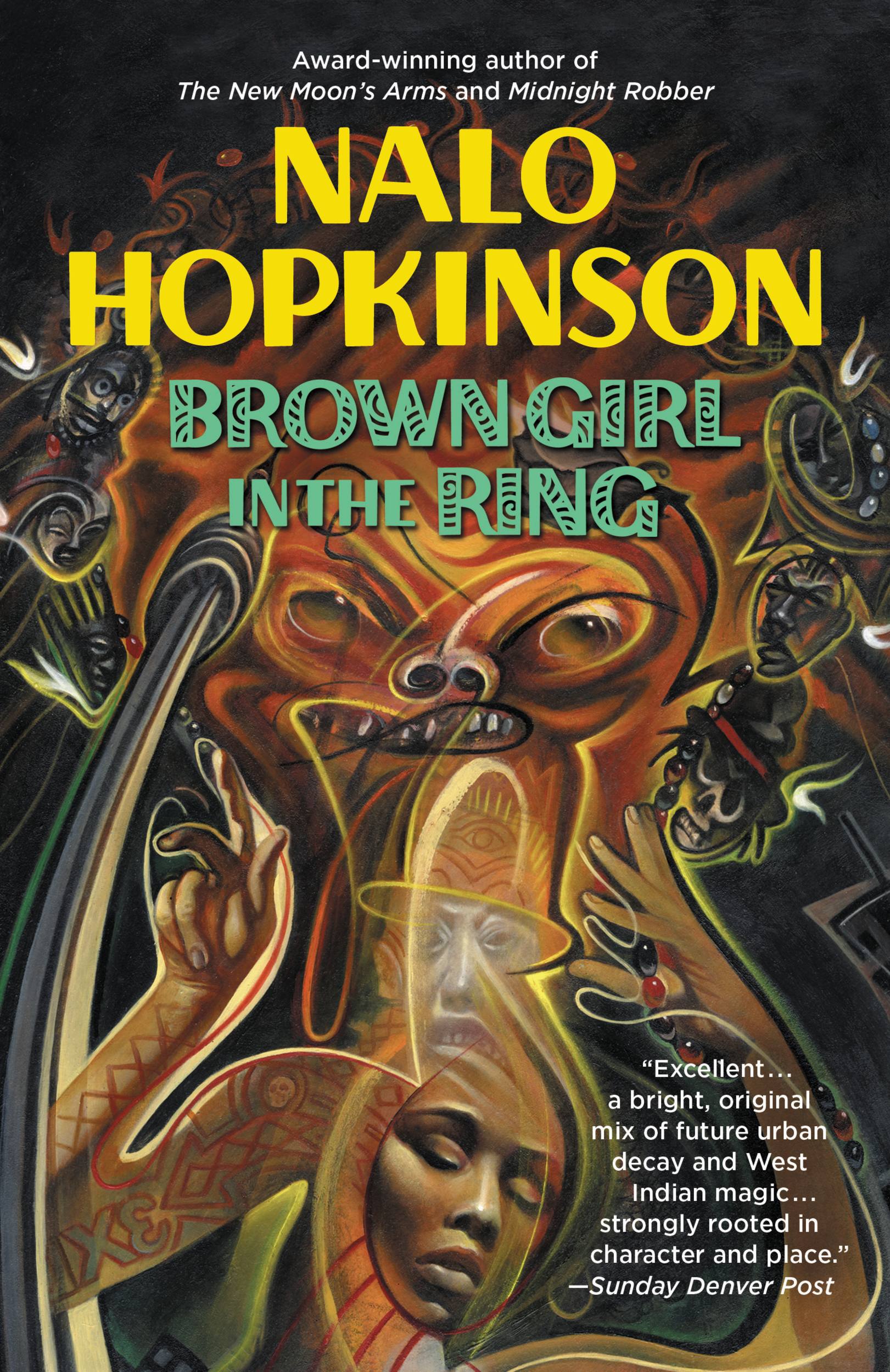

Brown Girl in the Ring

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$5.99Price

$7.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $5.99 $7.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 15, 2001. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The rich and privileged have fled the city, barricaded it behind roadblocks, and left it to crumble. The inner city has had to rediscover old ways — farming, barter, herb lore. But now the monied need a harvest of bodies, and so they prey upon the helpless of the streets. With nowhere to turn, a young woman must open herself to ancient truths, eternal powers, and the tragic mystery surrounding her mother and grandmother. She must bargain with gods, and give birth to new legends.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 15, 2001

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780759520448

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use