Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

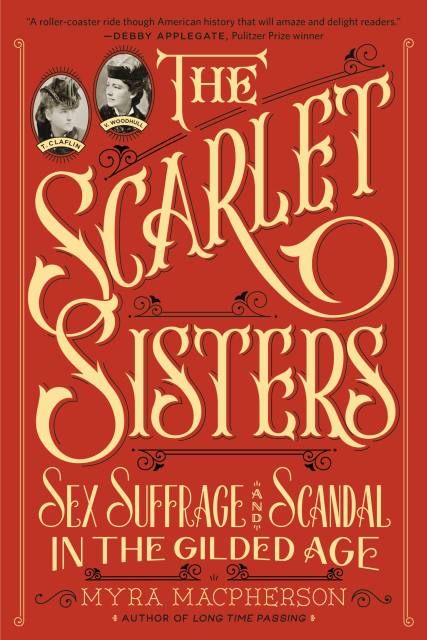

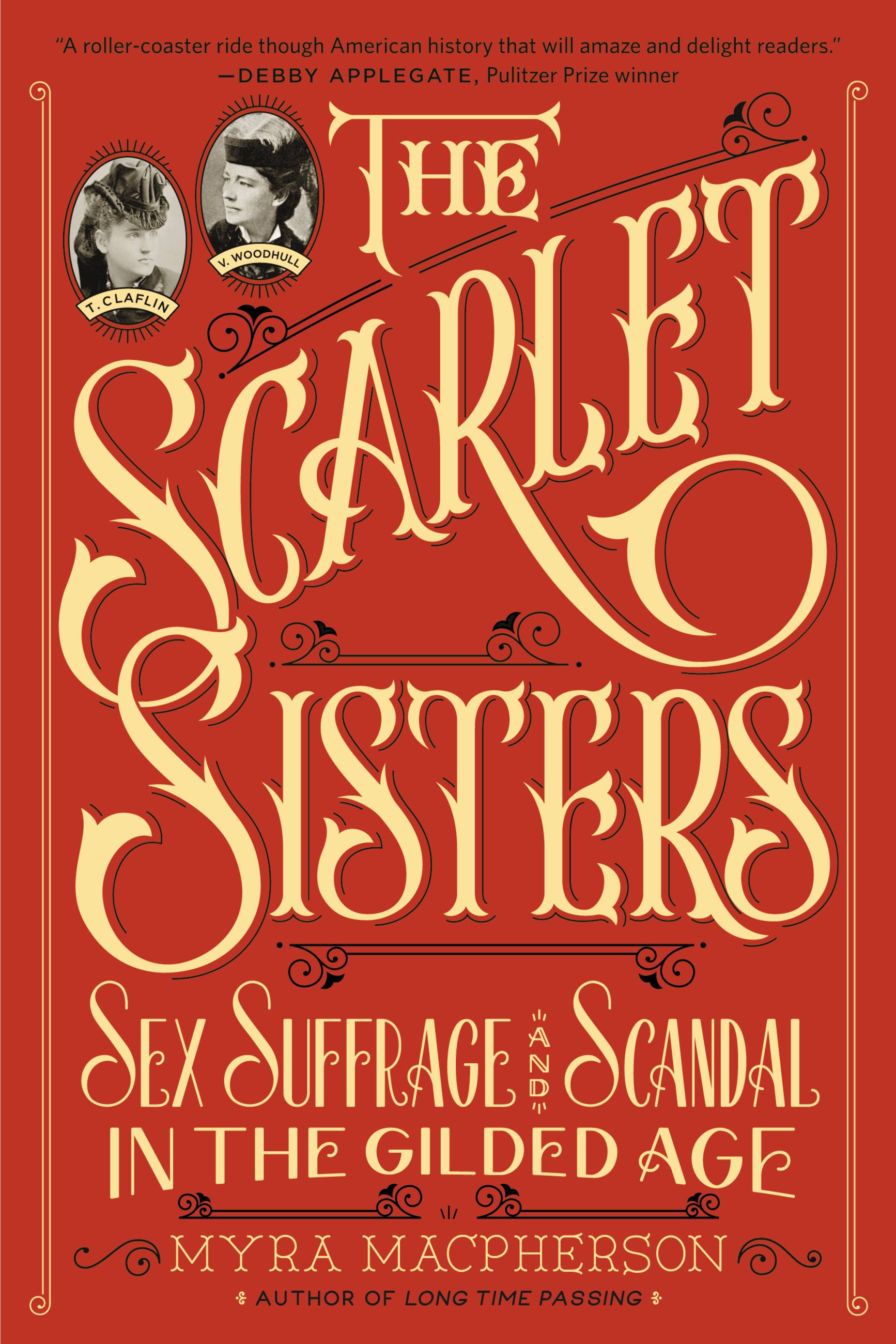

The Scarlet Sisters

Sex, Suffrage, and Scandal in the Gilded Age

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 4, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A fresh look at the life and times of Victoria Woodhull and Tennie Claflin, two sisters whose radical views on sex, love, politics, and business threatened the white male power structure of the nineteenth century and shocked the world. Here award-winning author Myra MacPherson deconstructs and lays bare the manners and mores of Victorian America, remarkably illuminating the struggle for equality that women are still fighting today.

Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee “Tennie” Claflin-the most fascinating and scandalous sisters in American history-were unequaled for their vastly avant-garde crusade for women’s fiscal, political, and sexual independence. They escaped a tawdry childhood to become rich and famous, achieving a stunning list of firsts. In 1870 they became the first women to open a brokerage firm, not to be repeated for nearly a century.

Amid high gossip that he was Tennie’s lover, the richest man in America, fabled tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, bankrolled the sisters. As beautiful as they were audacious, the sisters drew a crowd of more than two thousand Wall Street bankers on opening day. A half century before women could vote, Victoria used her Wall Street fame to become the first woman to run for president, choosing former slave Frederick Douglass as her running mate. She was also the first woman to address a United States congressional committee. Tennie ran for Congress and shocked the world by becoming the honorary colonel of a black regiment.

They were the first female publishers of a radical weekly, and the first to print Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto in America. As free lovers they railed against Victorian hypocrisy and exposed the alleged adultery of Henry Ward Beecher, the most famous preacher in America, igniting the “Trial of the Century” that rivaled the Civil War for media coverage. Eventually banished from the women’s movement while imprisoned for allegedly sending “obscenity” through the mail, the sisters sashayed to London and married two of the richest men in England, dining with royalty while pushing for women’s rights well into the twentieth century. Vividly telling their story, Myra MacPherson brings these inspiring and outrageous sisters brilliantly to life.

Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee “Tennie” Claflin-the most fascinating and scandalous sisters in American history-were unequaled for their vastly avant-garde crusade for women’s fiscal, political, and sexual independence. They escaped a tawdry childhood to become rich and famous, achieving a stunning list of firsts. In 1870 they became the first women to open a brokerage firm, not to be repeated for nearly a century.

Amid high gossip that he was Tennie’s lover, the richest man in America, fabled tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, bankrolled the sisters. As beautiful as they were audacious, the sisters drew a crowd of more than two thousand Wall Street bankers on opening day. A half century before women could vote, Victoria used her Wall Street fame to become the first woman to run for president, choosing former slave Frederick Douglass as her running mate. She was also the first woman to address a United States congressional committee. Tennie ran for Congress and shocked the world by becoming the honorary colonel of a black regiment.

They were the first female publishers of a radical weekly, and the first to print Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto in America. As free lovers they railed against Victorian hypocrisy and exposed the alleged adultery of Henry Ward Beecher, the most famous preacher in America, igniting the “Trial of the Century” that rivaled the Civil War for media coverage. Eventually banished from the women’s movement while imprisoned for allegedly sending “obscenity” through the mail, the sisters sashayed to London and married two of the richest men in England, dining with royalty while pushing for women’s rights well into the twentieth century. Vividly telling their story, Myra MacPherson brings these inspiring and outrageous sisters brilliantly to life.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 4, 2014

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455547708

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use