By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

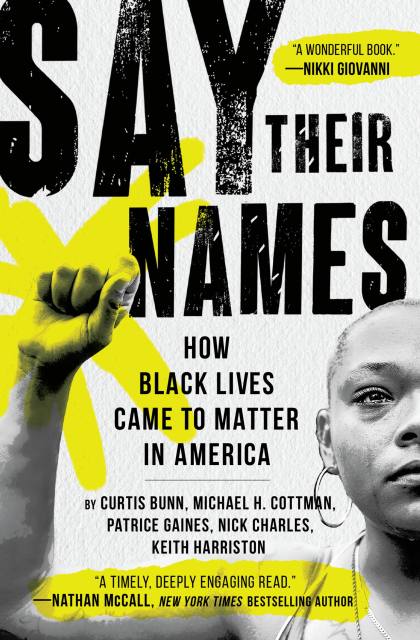

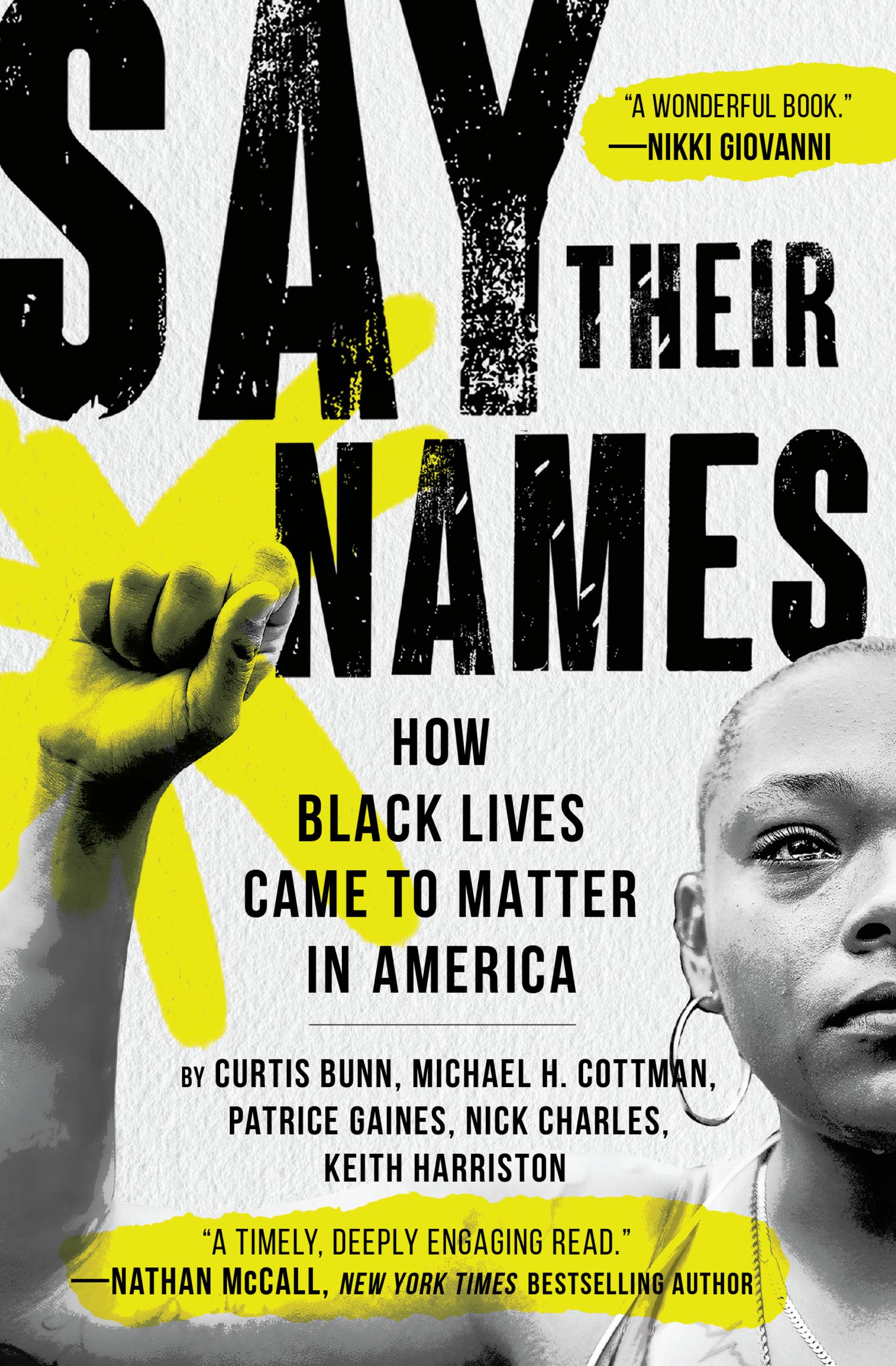

Say Their Names

How Black Lives Came to Matter in America

Contributors

By Patrice Gaines

By Curtis Bunn

By Nick Charles

By Keith Harriston

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 5, 2021

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538737842

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 5, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For many, the story of the weeks of protests in the summer of 2020 began with the horrific nine minutes and twenty-nine seconds when Police Officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd on camera, and it ended with the sweeping federal, state, and intrapersonal changes that followed. It is a simple story, wherein white America finally witnessed enough brutality to move their collective consciousness. The only problem is that it isn't true. George Floyd was not the first Black man to be killed by police—he wasn’t even the first to inspire nation-wide protests—yet his death came at a time when America was already at a tipping point.

In Say Their Names, five seasoned journalists probe this critical shift. With a piercing examination of how inequality has been propagated throughout history, from Black imprisonment and the Convict Leasing program to long-standing predatory medical practices to over-policing, the authors highlight the disparities that have long characterized the dangers of being Black in America. They examine the many moderate attempts to counteract these inequalities, from the modern Civil Rights movement to Ferguson, and how the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others pushed compliance with an unjust system to its breaking point. Finally, they outline the momentous changes that have resulted from this movement, while at the same time proposing necessary next steps to move forward.

With a combination of penetrating, focused journalism and affecting personal insight, the authors bring together their collective years of reporting, creating a cohesive and comprehensive understanding of racial inequality in America.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use