Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

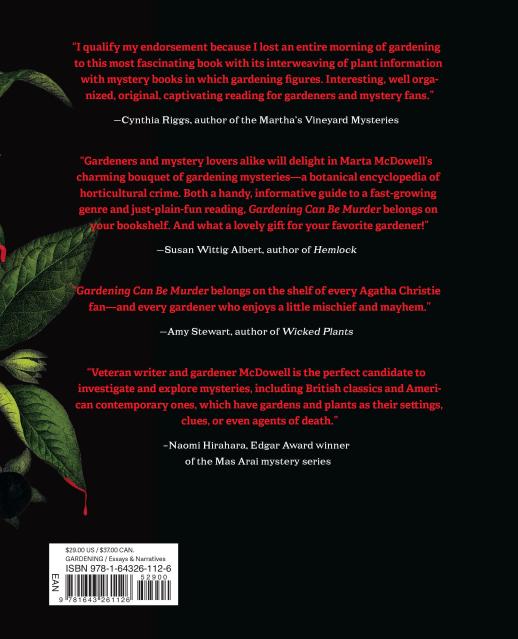

Gardening Can Be Murder

How Poisonous Poppies, Sinister Shovels, and Grim Gardens Have Inspired Mystery Writers

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2023

- Page Count

- 216 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643261126

Price

$29.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

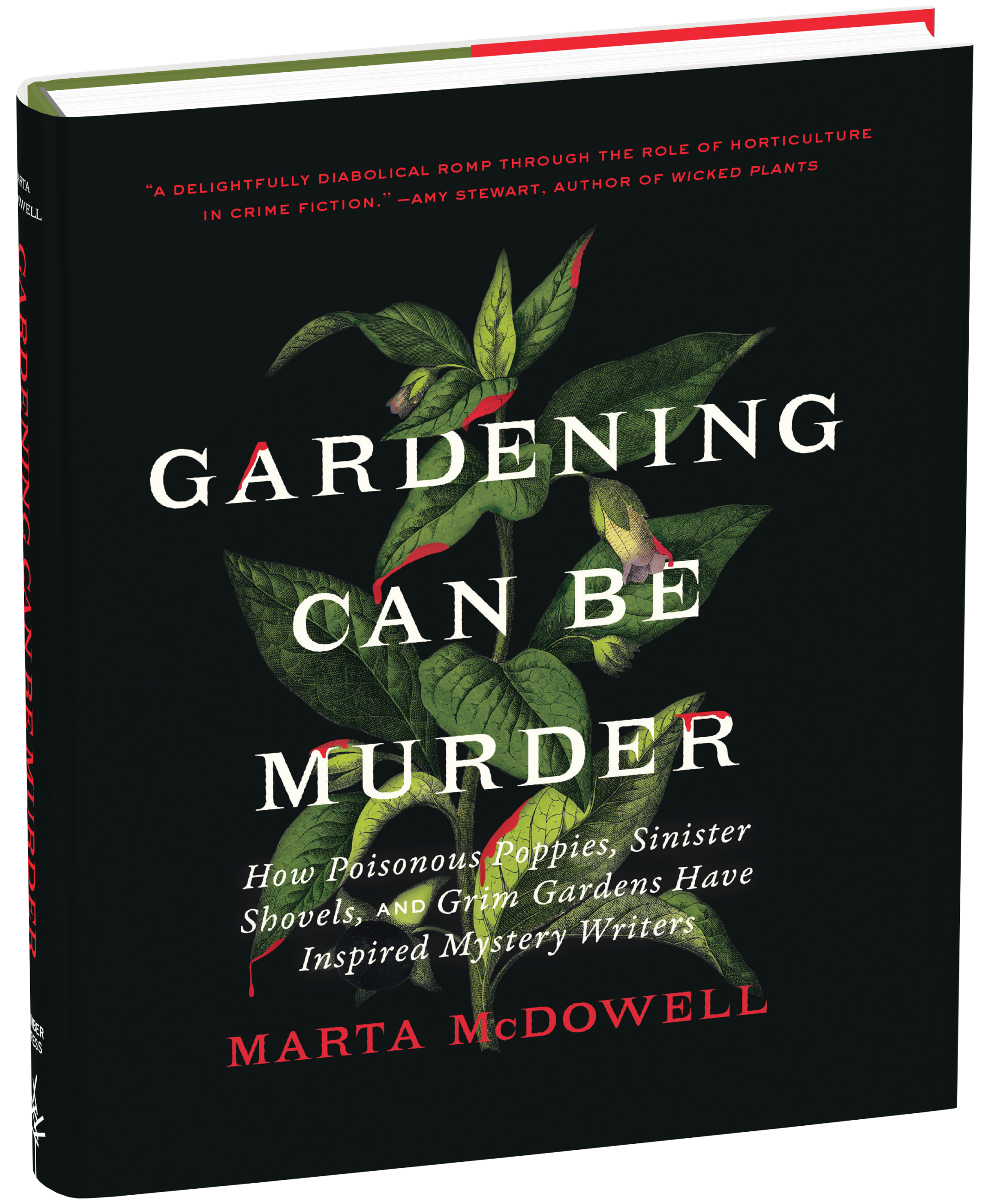

“This book is dangerous. A veritable cornucopia of crime fiction and gardening lore, it faces the reader with multiple temptations—books to seek out, plants to obtain, garden tours to book.” —Vicki Lane, author of the Elizabeth Goodweather Appalachian Mysteries

“Belongs on the shelf of every Agatha Christie fan—and every gardener who enjoys a little mischief and mayhem.” ―Amy Stewart, author of Wicked Plants

With their deadly plants, razor-sharp shears, shady corners, and ready-made burial sites, gardens make an ideal scene for the perfect murder. In Gardening Can Be Murder Marta McDowell, a writer and gardener with a near-encyclopedic knowledge of the genre, illuminates the many ways in which our greatest mystery writers, from Edgar Allen Poe to authors on today’s bestseller lists, have found inspiration in the sinister side of gardens.

From the cozy to the hardboiled, the literary to the pulp, and the classic to the contemporary, this book explores the mystery genre’s many surprising horticultural connections. Meet plant-obsessed detectives and spooky groundskeeper suspects, witness toxic teas served in foul play, and tour the gardens—both real and imagined—that have been the settings for fiction’s ghastliest misdeeds. McDowell also introduces us to today’s top writers who consider gardening integral to their craft, assuring that horticultural themes will remain a staple of the genre for countless twisting plots to come.

-

“What could be more intriguing than a murder in the garden? In her newest book, Marta McDowell takes us on a delightfully diabolical romp through the role of horticulture in crime fiction. From deadly seeds, to menacing pruning shears, to suspicious groundskeepers, the garden has always provided both the motive and means to commit the perfect crime. Gardening Can Be Murder belongs on the shelf of every Agatha Christie fan—and every gardener who enjoys a little mischief and mayhem.”Amy Stewart, author of Wicked Plants

-

“I qualify my endorsement because I lost an entire morning of gardening to this most fascinating book with its interweaving of plant information with mystery books in which gardening figures. I am now torn – do I rush out to the garden to prune the hop vine, or shall I retrieve one of my Brother Cadfael mysteries from the upstairs bookcase? Interesting, well organized, original, captivating reading for gardeners and mystery fans.”Cynthia Riggs, author of the Martha’s Vineyard Mysteries

-

“This book is dangerous. A veritable cornucopia of crime fiction and gardening lore, it faces the reader with multiple temptations—books to seek out, plants to obtain, garden tours to book. It’s a delightful wander through the mystery genre from Poe to Penny and its surprisingly numerous ties to gardening. Presented in McDowell’s elegant and accessible prose, it’s completely captivating.”Vicki Lane, author of the Elizabeth Goodweather Appalachian Mysteries

-

“Gardeners and mystery lovers alike will delight in Marta McDowell’s charming bouquet of gardening mysteries—a botanical encyclopedia of horticultural crime. Both a handy, informative guide to a fast-growing genre and just-plain-fun reading, Gardening Can Be Murder belongs on your bookshelf. And what a lovely gift for your favorite gardener!”Susan Wittig Albert, author of Hemlock

-

“Wonderful mash-ups of literature and gardening lore.”Vicki Lane Mysteries

-

"Marta McDowell digs up the dirt on an unsuspecting source of inspiration for the mystery genre: gardens. Gardening Can Be Murder marries McDowell's encyclopedic knowledge of plants and the murder-mystery genre. She documents every shady gardener and poisoned tea, consulting literary giants both classic and current along the way."Reader's Digest

-

“Delves into the many ways in which mystery writers have found inspiration from poisonous plants and the more sinister side of gardens.”Gardens Illustrated

-

“McDowell looks at gardens from the darker side of human nature — after all, gardening and obsession have long been willing bedfellows. You’ll meet gardening detectives and find out what happens when sharp tools and toxic potions fall into the wrong hands and which gardens, real or imagined, might prove to be the setting for a perfect crime. From Agatha Christie to Elizabeth George, Louise Penny to Ruth Rendell, Dorothy L. Sayers to Raymond Chandler, the reading list at the back of the book is to die for.”The Seattle Times

-

This fun, engrossing book takes a look at surprising influences gardens and gardening have had on mystery novels and their authors."The Joplin Globe

-

"McDowell’s delightful Gardening Can Be Murder covers other plant-obsessed detectives, from Agatha Christie’s flower enthusiast, Miss Marple, and Rex Stout’s orchid authority, Nero Wolfe, to Susan Wittig Albert’s herbalist, China Bayles. Potential weapons abound: lethal pesticides, razor-sharp pruning tools and spades that can deliver a fatal blow. The plants can be used for deadly purposes, too."Wall Street Journal

-

“McDowell’s packed pages are a spell-binding timeline detailing how the garden provides key clues across a landscape of classic to contemporary mystery novels."The Washington Gardener

-

“Dealing with the intriguing combination of gardening and murder is charming [if that’s a word you can use for such a macabre subject]. It’s also stylish, very well written, highly readable, entertaining, and enjoyable.”Plant Cuttings

-

“Clearly a connoisseur, McDowell holds up the mystery genre like a jewel and examines each of its facets with flair and imagination…Gardening Can Be Murder is one of the rare reference books that can be read cover to cover, or just dipped into for a title or two.”The Bulletin from Garden Clubs of America