Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

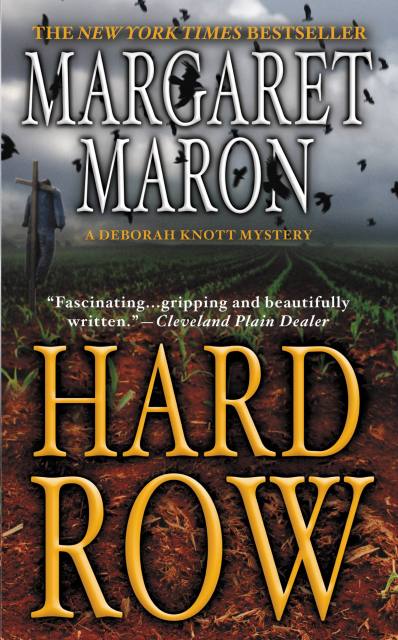

Hard Row

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $7.99 $9.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 22, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When another body is found, these newlyweds will discover dark truths that threaten to permanently alter the serenity of their rural surroundings and their new life together.

As Judge Deborah Knott presides over a case involving a barroom brawl, it becomes clear that deep resentments over race, class, and illegal immigration are simmering just below the surface in the countryside. An early spring sun has begun to shine like a blessing on the fertile fields of North Carolina, but along with the seeds sprouting in the thawing soil, violence is growing as well. Mutilated body parts have appeared along the back roads of Colleton County, and the search for the victim's identity and for that of his killer will lead Deborah and her new husband, Sheriff's Deputy Dwight Bryant, into the desperate realm of undocumented farm workers exploited for cheap labor.

In the meantime, Deborah and Dwight continue to adjust to married life and to having Dwight's eight-year-old son, Cal, live with them full time.

As Judge Deborah Knott presides over a case involving a barroom brawl, it becomes clear that deep resentments over race, class, and illegal immigration are simmering just below the surface in the countryside. An early spring sun has begun to shine like a blessing on the fertile fields of North Carolina, but along with the seeds sprouting in the thawing soil, violence is growing as well. Mutilated body parts have appeared along the back roads of Colleton County, and the search for the victim's identity and for that of his killer will lead Deborah and her new husband, Sheriff's Deputy Dwight Bryant, into the desperate realm of undocumented farm workers exploited for cheap labor.

In the meantime, Deborah and Dwight continue to adjust to married life and to having Dwight's eight-year-old son, Cal, live with them full time.

Series:

- On Sale

- Aug 22, 2007

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446198288

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use