By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

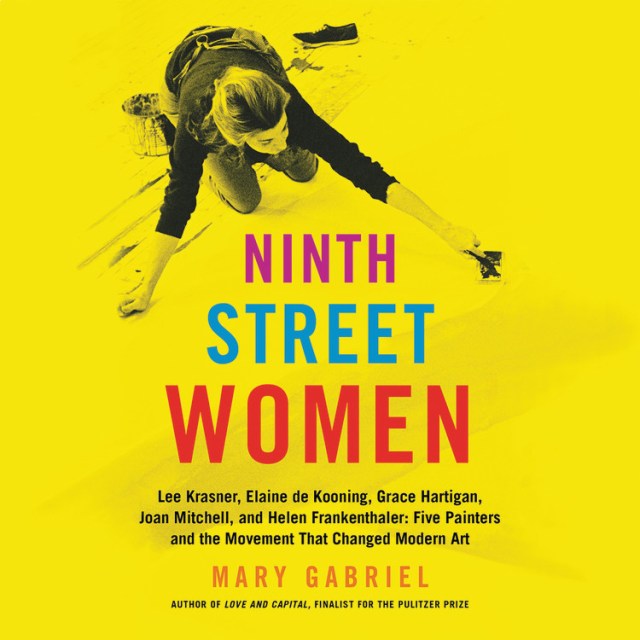

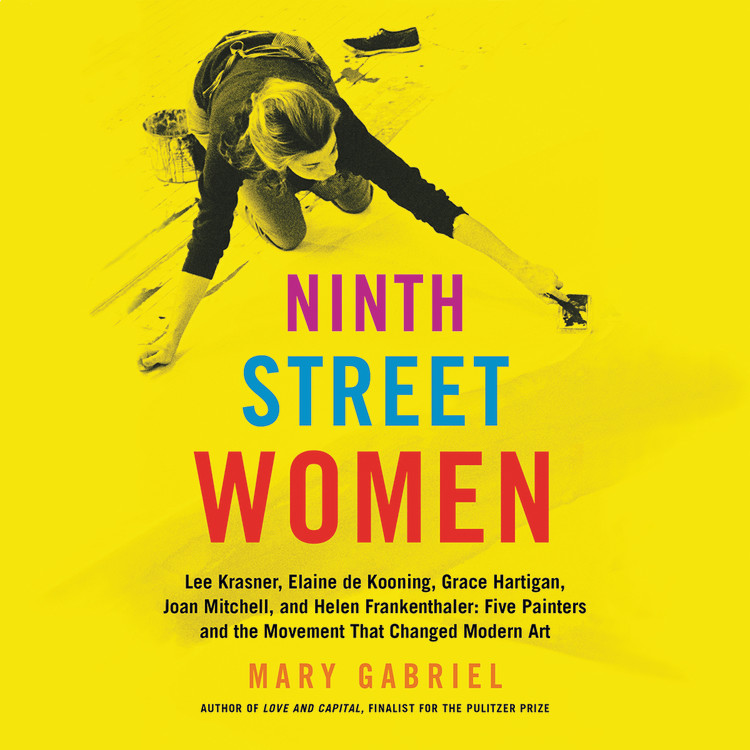

Ninth Street Women

Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art

Contributors

Read by Lisa Stathoplos

By Mary Gabriel

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 19, 2019

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549179198

Price

$49.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $49.99

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 19, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Set amid the most turbulent social and political period of modern times, Ninth Street Women is the impassioned, wild, sometimes tragic, always exhilarating chronicle of five women who dared to enter the male-dominated world of twentieth-century abstract painting — not as muses but as artists. From their cold-water lofts, where they worked, drank, fought, and loved, these pioneers burst open the door to the art world for themselves and countless others to come.

Gutsy and indomitable, Lee Krasner was a hell-raising leader among artists long before she became part of the modern art world’s first celebrity couple by marrying Jackson Pollock. Elaine de Kooning, whose brilliant mind and peerless charm made her the emotional center of the New York School, used her work and words to build a bridge between the avant-garde and a public that scorned abstract art as a hoax. Grace Hartigan fearlessly abandoned life as a New Jersey housewife and mother to achieve stardom as one of the boldest painters of her generation. Joan Mitchell, whose notoriously tough exterior shielded a vulnerable artist within, escaped a privileged but emotionally damaging Chicago childhood to translate her fierce vision into magnificent canvases. And Helen Frankenthaler, the beautiful daughter of a prominent New York family, chose the difficult path of the creative life.

Her gamble paid off: At twenty-three she created a work so original it launched a new school of painting. These women changed American art and society, tearing up the prevailing social code and replacing it with a doctrine of liberation. In Ninth Street Women, acclaimed author Mary Gabriel tells a remarkable and inspiring story of the power of art and artists in shaping not just postwar America but the future.

Genre:

-

"A gorgeous and unsettling narrative...Ninth Street Women is supremely gratifying, generous, and lush but also tough and precise -- in other words, as complicated and capacious as the lives it depicts...It's as if once Gabriel got started, the canvas before her opened up new vistas. We should be grateful she yielded to its possibilities."Jennifer Szalai, New York Times

-

"Ninth Street Women is like a great, sprawling Russian novel, filled with memorable characters and sharply etched scenes. It's no mean feat to breathe life into five very different and very brave women, none of whom gave a whit about conventional mores. But Ms. Gabriel fleshes out her portraits with intimate details, astute analyses of the art and good old-fashioned storytelling."Ann Landi, Wall Street Journal

-

"Ninth Street Women is a must read...Gabriel seamlessly weaves the intimate and the public, the lives and the art, making us feel we were there...It is a story that is a part of the American story, told here in vivid, meaningful detail, an absolutely pivotal text."Margaret Randall, Women's Review of Books

-

"Gabriel's fascinating group portrait shimmers with vivid personal detail...She traces their interwoven paths from studio to Cedar Bar to the Eight Street loft known as the Club...Over time, Willem de Kooning outshone Elaine; Jackson Pollock eclipsed Krasner. Key contributions were erased...Gabriel makes sure these major artists who have been written out of history are not forgotten."Jane Ciabattari, BBC.com

-

"Masterful. Mixing critical insight with juicy storytelling, Mary Gabriel brings five brilliant female painters to the fore of the art revolution that cut a wide swath in postwar America."Patricia Albers, author of Joan Mitchell: Lady Painter

-

"Gripping and enthralling, Mary Gabriel made me share every turbulent moment of these remarkable women's lives. A magisterial reference, this book will be the definitive text for years to come. It is also the most devastatingly accurate portrayal of five women who had the temerity to call themselves artists in the male-dominated twentieth century."Deirdre Bair, author of Al Capone: His Life, Legacy, and Legend

-

"I loved every page of this necessary book. At last we see such once-sidelined artists as Joan Mitchell and Elaine de Kooning in depth, and both the telling gossip of their lives and the brave authenticity of their work are thrilling. Mary Gabriel restores the humanist ambition at the core of all the New York painters of this era, whether male or female--the boldness of their risky lives and the seriousness of their noble enterprise."Brad Gooch, author of Rumi's Secret: The Life of the Sufi Poet of Love

-

"Sheer delight. A richly detailed epic starring not only five heroic female painters, but a supporting cast that defines the entire existential and Beat era, from Frank O'Hara to Billie Holiday to Samuel Beckett. Gabriel's vision of Lee Krasner jazz dancing with Piet Mondrian alone is worth the price of the book. With palpable empathy for the flawed brilliance of her five stars, their jealous foes, and their long-suffering enablers, Gabriel conjures the high-risk paths they chose, what making great art cost their lives, and what they lost and won in the end."Michael Findlay, director of Acquavella Galleries and author of Seeing Slowly: Looking at Modern Art

-

"A colorful narrative as compelling as a novel. Gabriel brilliantly shows how the women of Abstract Expressionism carved out paths for themselves in an often hostile community, fashioning careers and producing exciting work fully as important as that of their male peers--men whom they befriended, married, bedded, or disdained."Mary V. Dearborn, author of Ernest Hemingway: A Biography

-

"A fascinating, meticulously researched account of five painters who broke through the gender barriers in the art world of the 1950s. Gabriel is deft at teasing out the behind-the-scenes drama in these women's lives and careers. Essential reading for any student of the period, and of the New York School generally."David Salle, author of How to See: Looking, Talking, and Thinking About Art

-

"A sweeping panorama of American art history in the decades around World War II--specifically Abstract Expressionism and the rise of U.S. art world dominance internationally. A major contribution to the literature of twentieth-century cultural and social history."Julia Van Haaften, author of Berenice Abbott: A Life in Photography

-

"Gabriel delivers an immersive group biography of eclectic, free-spirited painters who shocked the art world in the 1940s and '50s with abstract expressionism...Through the lens of these women's lives, Gabriel delivers a sweeping history of abstract expressionism and the postwar New York School, and an affectionate tribute to the underappreciated women of America's avant-garde."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Gabriel has created an ambitious, comprehensive, and impressively detailed history of abstract expressionism focused on the lives and works of Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler...A sympathetic, authoritative collective biography."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"Biographer Gabriel corrects long-standing misperceptions about New York's abstract-expressionism movement by telling the dramatic, often traumatic stories of the five gifted and courageous women painters at the center of that radical flowering...avidly researched, deeply analyzed, gorgeously written, and endlessly involving five-track mix of biography and history... Gabriel not only provides vibrantly detailed accounts of these five exceptional avant-garde artists' friendships and rivalries, affairs and marriages, doubt and despair, conviction and resilience; she also establishes a richly dimensional context for their struggles and innovations...Gabriel has created an incandescent, engrossing, and paradigm-altering art epic."Booklist (starred review)

-

"These individuals are brought to life by Pulitzer Prize finalist Gabriel, who shows how each defied social convention and professional boundaries to create new creative forms and attain equality with their male counterparts. . . . A must for modern art historians and enthusiasts."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"More than a compilation of biographical tales, Gabriel's book is a reminder of the importance of women to an artistic genre long associated with masculinity. But it is also is a vivid portrait of the very nature of the artist. The stars of the era suffered and sinned as mortals, but their works -- and their creative appetites -- were otherworldly. Ninth Street Women gets us a just a little bit closer to their galaxy."Karen Sandstrom, Washington Post

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use