By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

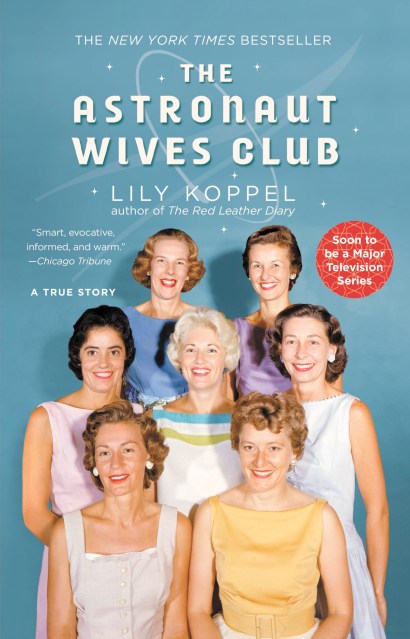

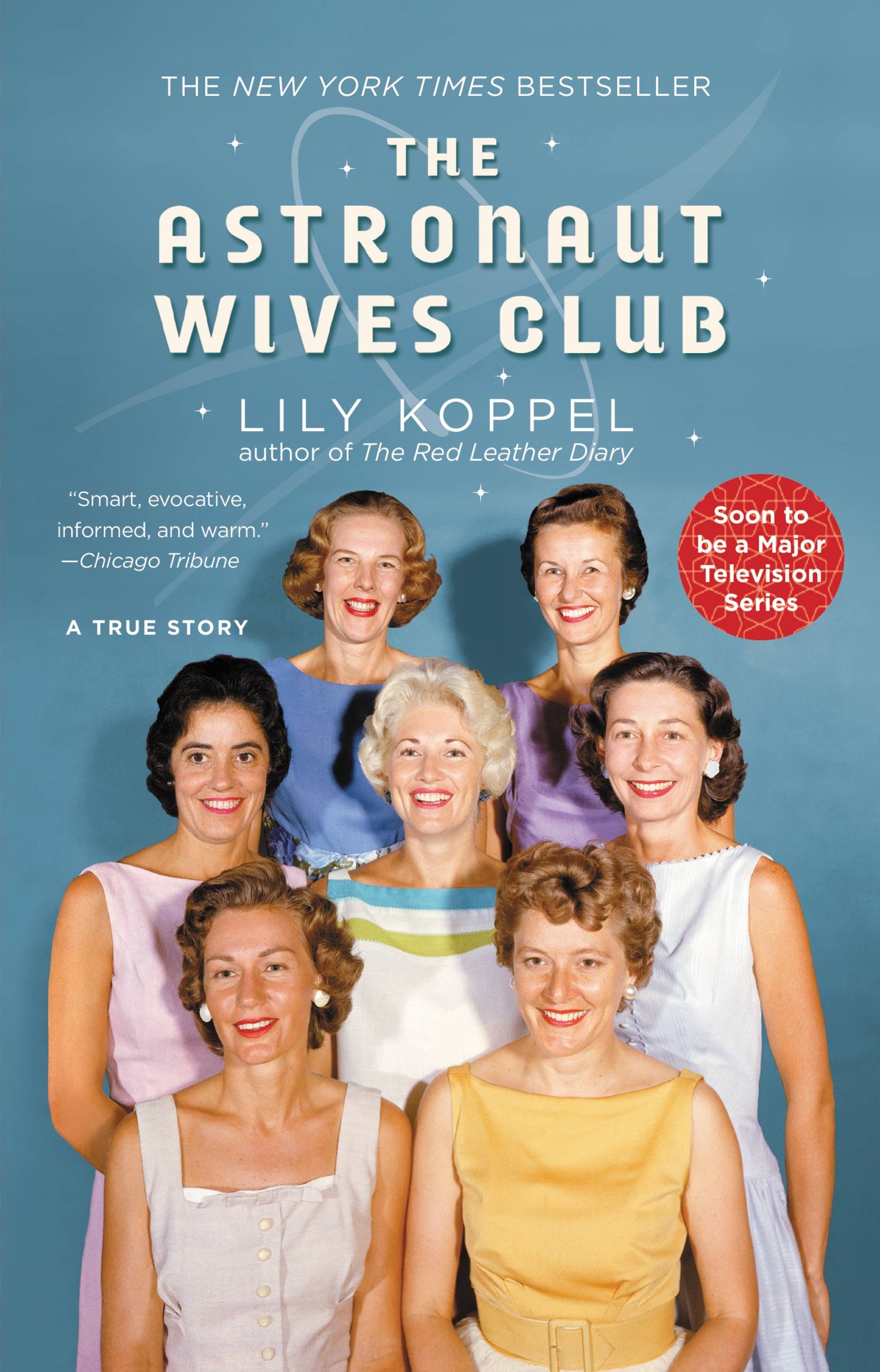

The Astronaut Wives Club

A True Story

Contributors

By Lily Koppel

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 3, 2014

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455503247

Price

$17.00Price

$20.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.00 $20.50 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 3, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As America’s Mercury Seven astronauts were launched on death-defying missions, television cameras focused on the brave smiles of their young wives. Overnight, these women were transformed from military spouses into American royalty. They had tea with Jackie Kennedy, appeared on the cover of Life magazine, and quickly grew into fashion icons.

Annie Glenn, with her picture-perfect marriage, was the envy of the other wives; JFK made it clear that platinum-blonde Rene Carpenter was his favorite; and licensed pilot Trudy Cooper arrived with a secret that needed to stay hidden from NASA. Together with the other wives they formed the Astronaut Wives Club, providing one another with support and friendship, coffee and cocktails.

As their celebrity rose-and as divorce and tragedy began to touch their lives-the wives continued to rally together, forming bonds that would withstand the test of time, and they have stayed friends for over half a century. THE ASTRONAUT WIVES CLUB tells the story of the women who stood beside some of the biggest heroes in American history.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use