By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

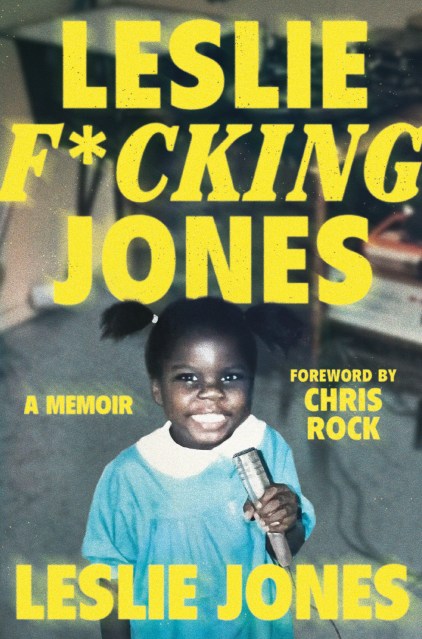

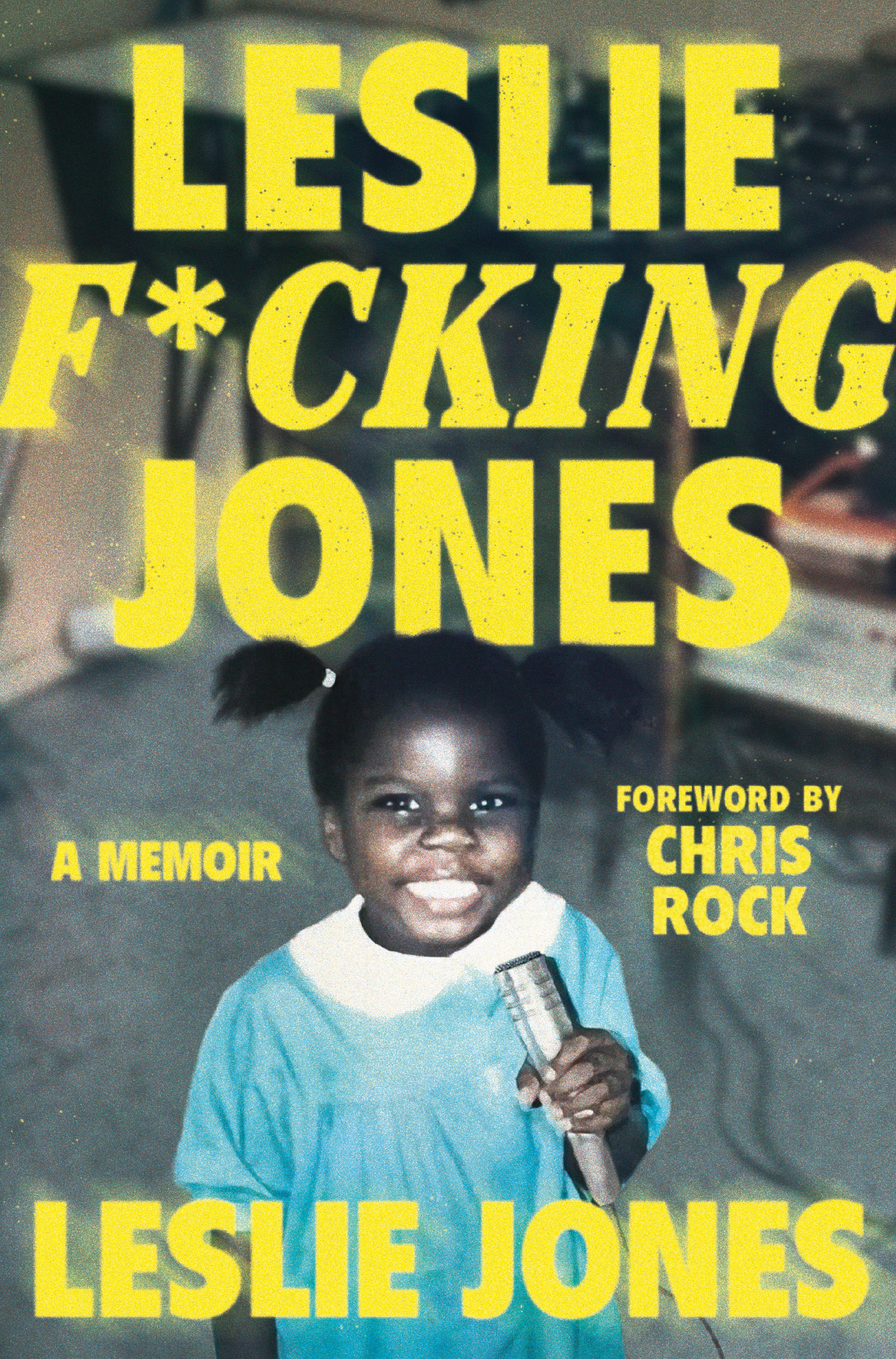

Leslie F*cking Jones

Contributors

By Leslie Jones

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 19, 2023

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538706497

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 19, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

A BARNES AND NOBLE’S BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR

A TOWN & COUNTRY BEST CELEBRITY MEMOIR OF 2023

A VULTURE BEST COMEDY BOOK OF 2023

Hey you guys, it’s Leslie. I’m excited to share my story with you.

Now, I’m gonna be honest: Some of the details might be vague because a b*tch is fifty-five and she’s smoked a ton of weed. But while bits might be a touch hazy, I can promise you the underlying truth is REAL. Whether I’m talking about my childhood growing up in the South, my early stand-up days driving from gig to gig through the darkest parts of our country and praying I wouldn’t get murdered, what Chris Rock told Lorne Michaels, that time I wanted to shoot Whoopi Goldberg on SNL, and yeah, I’ll tell you all about Ghostbusters and the nudes and Supermarket Sweep and The Daily Show . . . I’m sharing it all in these pages. It’s not easy being a woman in comedy, especially when you’re a tall-*ss Black woman with a trumpet voice. I have to fight so that no one takes me for granted, and no one takes advantage. These are the stories that explain why. (Cue the Law & Order theme.)

Genre:

-

"This is not the kind of comedian memoir that’s an extension of the act, an explicit provider of context, or a personal-branding exercise. This is a conversational celebration of the force of nature that is Leslie Jones from the world’s foremost expert on Leslie Jones."Vulture

-

"This refreshingly uncensored book will appeal to Jones’ many fans and to anyone who appreciates the struggles Black female comics face on the road to success."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Coming in with the best title of a memoir this season, Leslie Jones is here to share, and we’re glad she did. . .Guaranteed to be funny and interesting.""New York Post

-

"Jones fans will enjoy the stories of a working comic on the road, behind-the-scenes “SNL” tidbits. . . In the end, it’s best consumed as life advice, even if the life led by the one giving the advice is entirely unique."AP News

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use