Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

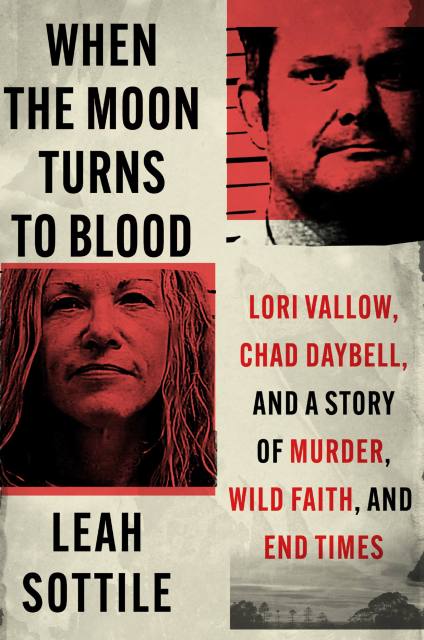

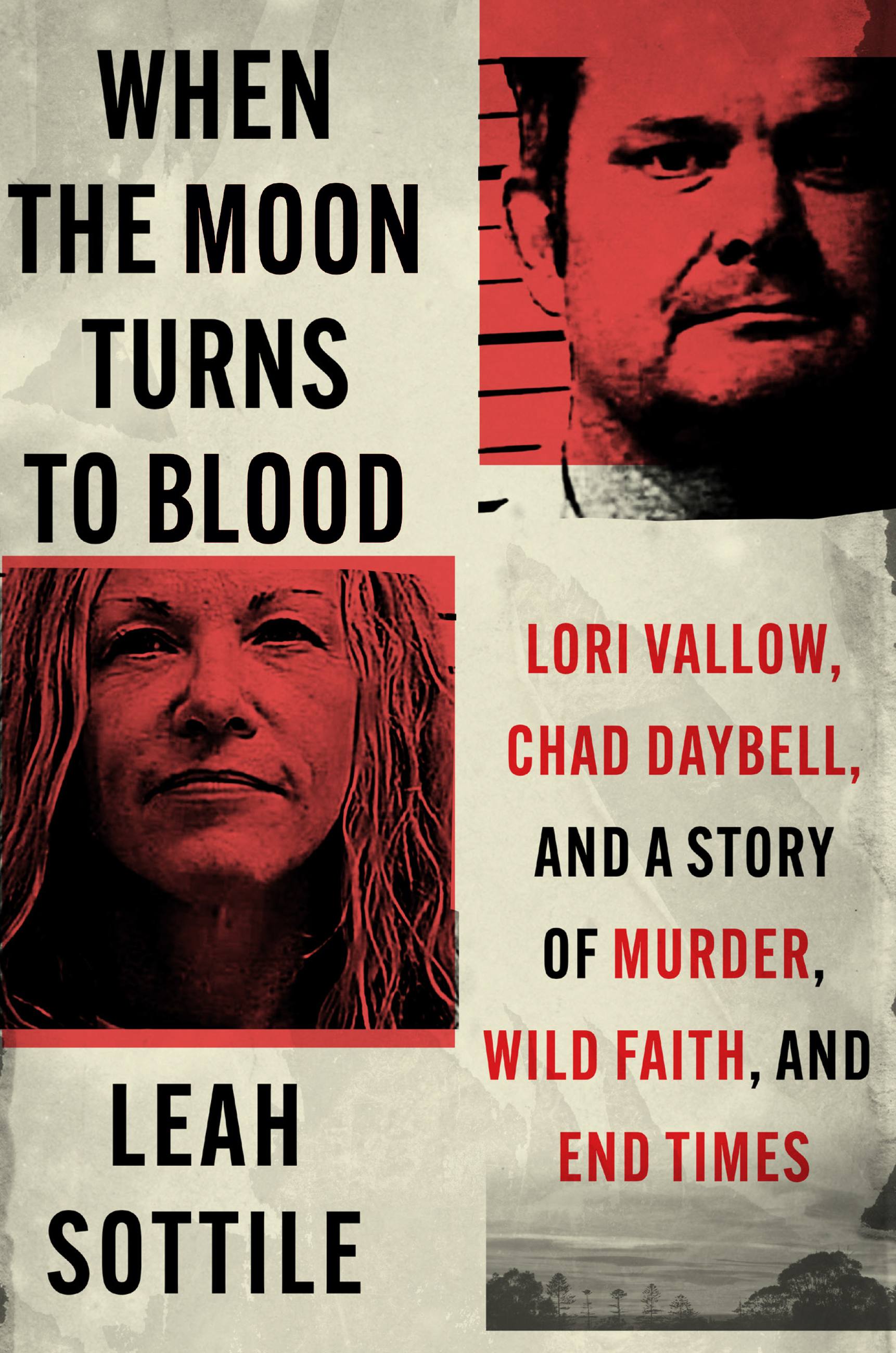

When the Moon Turns to Blood

Lori Vallow, Chad Daybell, and a Story of Murder, Wild Faith, and End Times

Contributors

By Leah Sottile

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 21, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When police in Rexburg, Idaho perform a wellness check on seven J.J. Vallow and his sister, sixteen-year-old Tylee Ryan, both children are nowhere to be found. Their mother, Lori Vallow, gives a phony explanation, and when officers return the following day with a search warrant, she, too, is gone. As the police begin to close in, a larger web of mystery, murder, fanaticism and deceit begins to unravel.

Vallow’s case is sinuously complex. As investigators prod further, they find the accused Black Widow has an unusual number of bodies piling up around her.

WHEN THE MOON TURNS TO BLOOD tells a gripping story of extreme beliefs, snake oil prophets, and explores the question: if it feels like the world is ending, how are people supposed to act?

Genre:

-

"WHEN THE MOON TURNS TO BLOOD is a harrowing and fascinating tale of apocalyptic obsession and murder. Leah Sottile leads us down every head-shaking twist and turn of the case, an expert guide to the dark tributaries of religious extremism that run closer to the American mainstream than we’d ever like to believe."Jess Walter, American author of seven novels, including #1 New York Times bestseller Beautiful Ruins

-

“Through scrupulous reporting and a powerful narrative, Leah Sottile takes us into a dark world of dysfunctional families, perverted faith, false prophets and true psychopaths to show us that the human mind is the scariest realm of all. An important contribution to the literature of true crime.”Mark Olshaker, coauthor of Mindhunter, The Killer Across the Table, and When a Killer Calls

-

“Leah Sottile’s brilliant, unnerving WHEN THE MOON TURNS TO BLOOD weaves the story of one family’s tragedy into an exploration of end-times radicalism that spans generations. It belongs on the short list of essential books about religious extremism and violence in the West.”Shawn Vestal, Columnist at The Spokesman-Review and author of Godforsaken Idaho

-

"Beyond a crime story, Sottile weaves a ripper of tale - chilling, haunting, cautionary too! - that unveils the dangerous desire for acceptance on the fringes, and amid uncertain times. Insanely researched in scope, uniquely intimate in feel, buckle-up for this brave voyage into a tangled storm of ambition, lust and extremism."Geoff Gray, author of Skyjack

-

"Leah Sottile is the writer every journalist dreams of being: A crackerjack investigator who has a nose for the telling details everyone else misses, and a gifted writer who can craft a moving literary narrative. Most of all, WHEN THE MOON TURNS TO BLOOD is an important book whose real subject is far more than a simple, horrifying murder case: It is a gut-wrenching fable about our upside-down, gaslit times, and what it tells us about ourselves and our susceptibility to the unreality of authoritarian conspiracism is profoundly disturbing. Everyone should read it."David Neiwert, journalist and author of Red Pill, Blue Pill and Alt-America

-

“From one of the finest chroniclers of the U.S. Northwest working today, this book hooked me from the first line. In propulsive prose, Leah Sottile unspools a harrowing story of faith, violence, and fear. WHEN THE MOON TURNS TO BLOOD is a timely and provocative page-turner, as resonant as it is engrossing. In Sottile’s hands, a true crime yarn becomes a lens for examining the most pernicious aspects of far-right extremism in America.”Seyward Darby, author of Sisters in Hate

-

"This book, wide in scope and remarkable for its timeliness, is a riveting account of the entire case (which is currently awaiting trial), including an exquisitely researched history of LDS and its fringe offshoots."Booklist Starred Review

-

"I think it’s a critical book for understanding 21st century Mormonism. If there’s a Mormon Studies class held anywhere in the United States or the world, this is one of the books that needs to be added to the reading list. That’s how critical I think this book is."Dr. John Dehlin, host of The Mormon Stories podcast

- On Sale

- Jun 21, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538721353

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use