Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

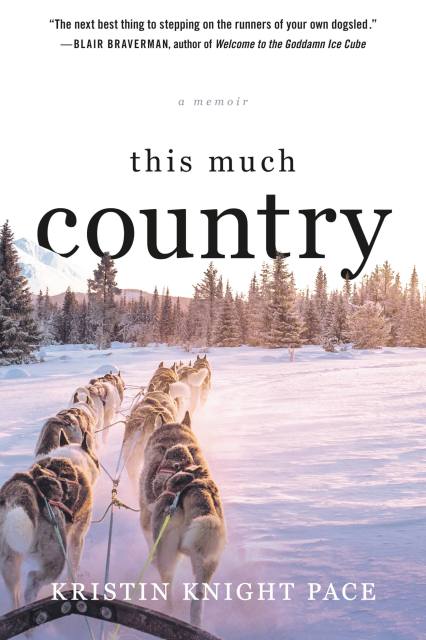

This Much Country

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538762394

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A memoir of heartbreak, thousand-mile races, the endless Alaskan wilderness and many, many dogs from one of only a handful of women to have completed both the Yukon Quest and the Iditarod.

That winter, she learned that she was tougher than she ever knew. She learned how to survive in one of the most remote places on earth and she learned she was strong enough to be alone. She fell in love twice: first with running sled dogs, and then with Andy, a gentle man who had himself moved to Alaska to heal a broken heart.

Kristin and Andy married and started a sled dog kennel. While this work was enormously satisfying, Kristin became determined to complete the Iditarod — the 1,000-mile dogsled race from Anchorage, in south central Alaska, to Nome on the western Bering Sea coast.

THIS MUCH COUNTRY is the story of renewal and transformation. It’s about journeying across a wild and unpredictable landscape and finding inner peace, courage and a true home. It’s about pushing boundaries and overcoming paralyzing fears.

In 2009, after a crippling divorce that left her heartbroken and directionless, Kristin decided to accept an offer to live at a friend’s cabin outside of Denali National Park in Alaska for a few months. In exchange for housing, she would take care of her friend’s eight sled dogs.

That winter, she learned that she was tougher than she ever knew. She learned how to survive in one of the most remote places on earth and she learned she was strong enough to be alone. She fell in love twice: first with running sled dogs, and then with Andy, a gentle man who had himself moved to Alaska to heal a broken heart.

Kristin and Andy married and started a sled dog kennel. While this work was enormously satisfying, Kristin became determined to complete the Iditarod — the 1,000-mile dogsled race from Anchorage, in south central Alaska, to Nome on the western Bering Sea coast.

THIS MUCH COUNTRY is the story of renewal and transformation. It’s about journeying across a wild and unpredictable landscape and finding inner peace, courage and a true home. It’s about pushing boundaries and overcoming paralyzing fears.

-

"THIS MUCH COUNTRY is the next best thing to stepping on the runners of your own dogsled. A gorgeous, intimate story of wildness and belonging."Blair Braverman, author of Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube

-

"Kristin Knight Pace is an adventurer not because of her experience in the wild, dogsledding across the tundra, but because of her fearless approach to life. A bad marriage, a failed business, a betrayal-none of this keeps her from pursuing her Alaska dream. A brave story, beautifully told."Leigh Newman, author of Still Points North

-

"Reading This Much Country is an utterly transporting experience; Kristin Knight Pace writes about the Alaskan wilderness with the tenderness of a lover. An absolute page- turner for those who love wild places, dogs, adventure, and those who just wish they did, Pace's story will have you asking yourself what it means to really live a life."Amy Shearn, author of The Mermaid of Brooklyn and How Far Is The Ocean fromHere

-

"This Much Country, ultimately, is a soul-warming story about setting goals, loving those you're with (including the dogs), and finding accomplishment and joy in every step of the way."Anchorage Daily News

-

"In her new memoir, This Much Country, Kristin Knight Pace writes movingly and candidly about the challenges she faced, and in so doing developed a renewed faith in her ability to take care of herself, no matter how daunting the circumstances."Salon

-

"This Much Country is an honest, heartfelt, and exciting memoir and a must-read for all nature lovers seeking a glimpse into a truly Alaskan adventure."Booklist (starred review)

-

"An intriguing account of one woman's quest to redefiner herself in a land that mirrors her own wild spirit. Will appeal to a multitude of readers, particularly fans of Cheryl Strayed's Wild."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"A vibrant memoir of sled dog racing in the wilds of Alaska. Much of the memoir recounts Pace's training for and racing in the Yukon Quest and the Iditarod, both exhausting, exhilarating, and, as Pace depicts them, glorious feats. A buoyant evocation of a thrilling, hardscrabble life."Kirkus

-

"Pace is candid about life in the frozen north, and her self-awareness makes this a worthy addition to the outdoor adventure genre."Publisher's Weekly

-

"[Kristin] doesn't gloss over the tough parts of Alaskan life: isolation, no running water, almost total darkness in wintertime. But her journalist's eye for detail is strongest when she writes about racing itself and describes the personalities of her beloved dogs. Her descriptions of the wide, wild country will captivate readers, even those who are not wilderness-inclined."Shelf Awareness