Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

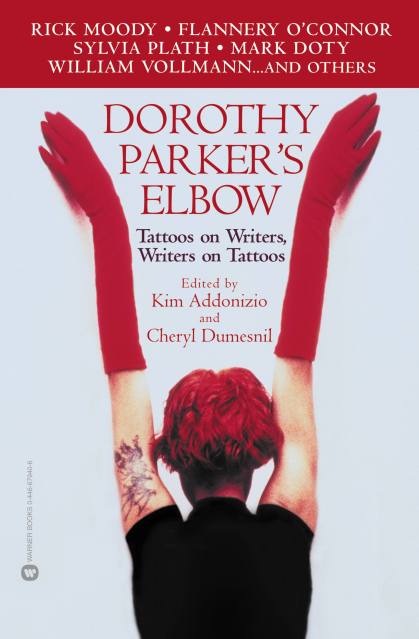

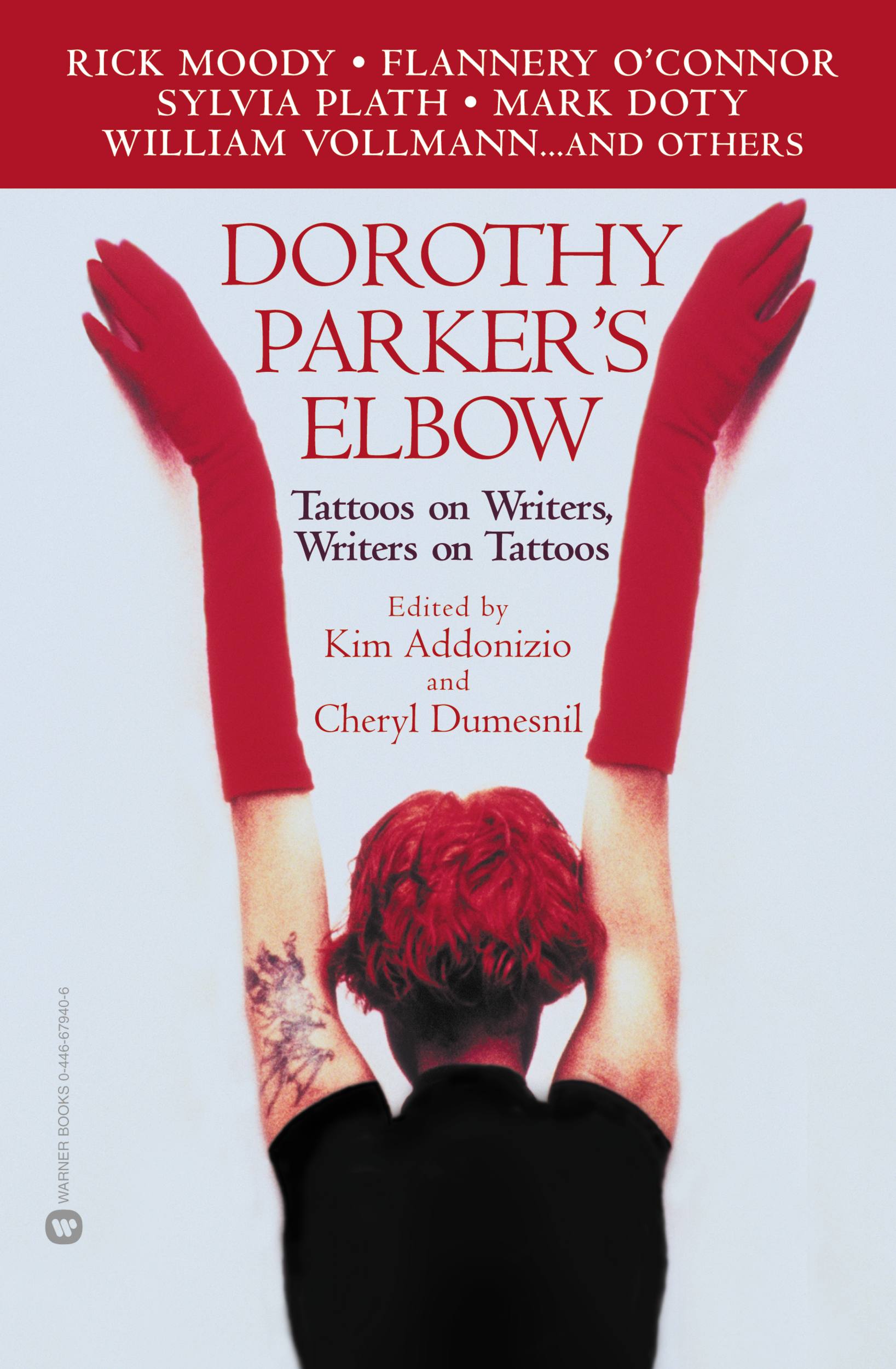

Dorothy Parker's Elbow

Tattoos on Writers, Writers on Tattoos

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 31, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Previously considered the domain of bikers and a rite of passage in the army, tattoos have crawled out of society’s fringes and onto the ankles of starlets and the biceps of bankers. While still risque enough to raise a mother-in-law’s eyebrow, tattoos have come to be one of the most popular forms of personal expression. DOROTHY PARKER’S ELBOW brings together some of the most erotic, humorous, and vivid fiction, essays, and poetry that explore the mysterious fascination and the intensity of emotion attached to the act of being tattooed. Readers will join great writers, including Flannery O’Connor, Rick Moody, Elizabeth McCracken, Sylvia Plath, and more in celebrating the tattoo experience in all of its rebellious glory.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 31, 2009

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446568531

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use