Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

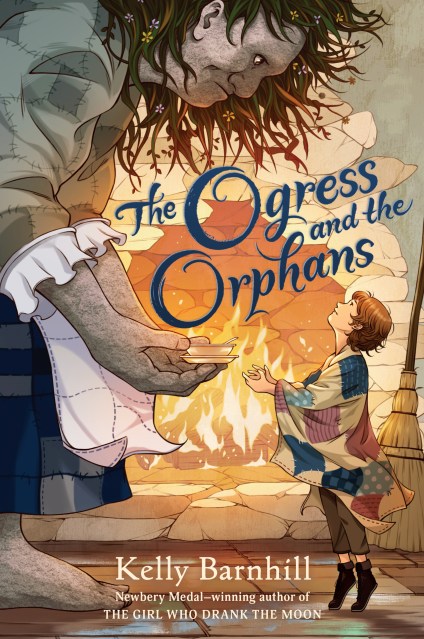

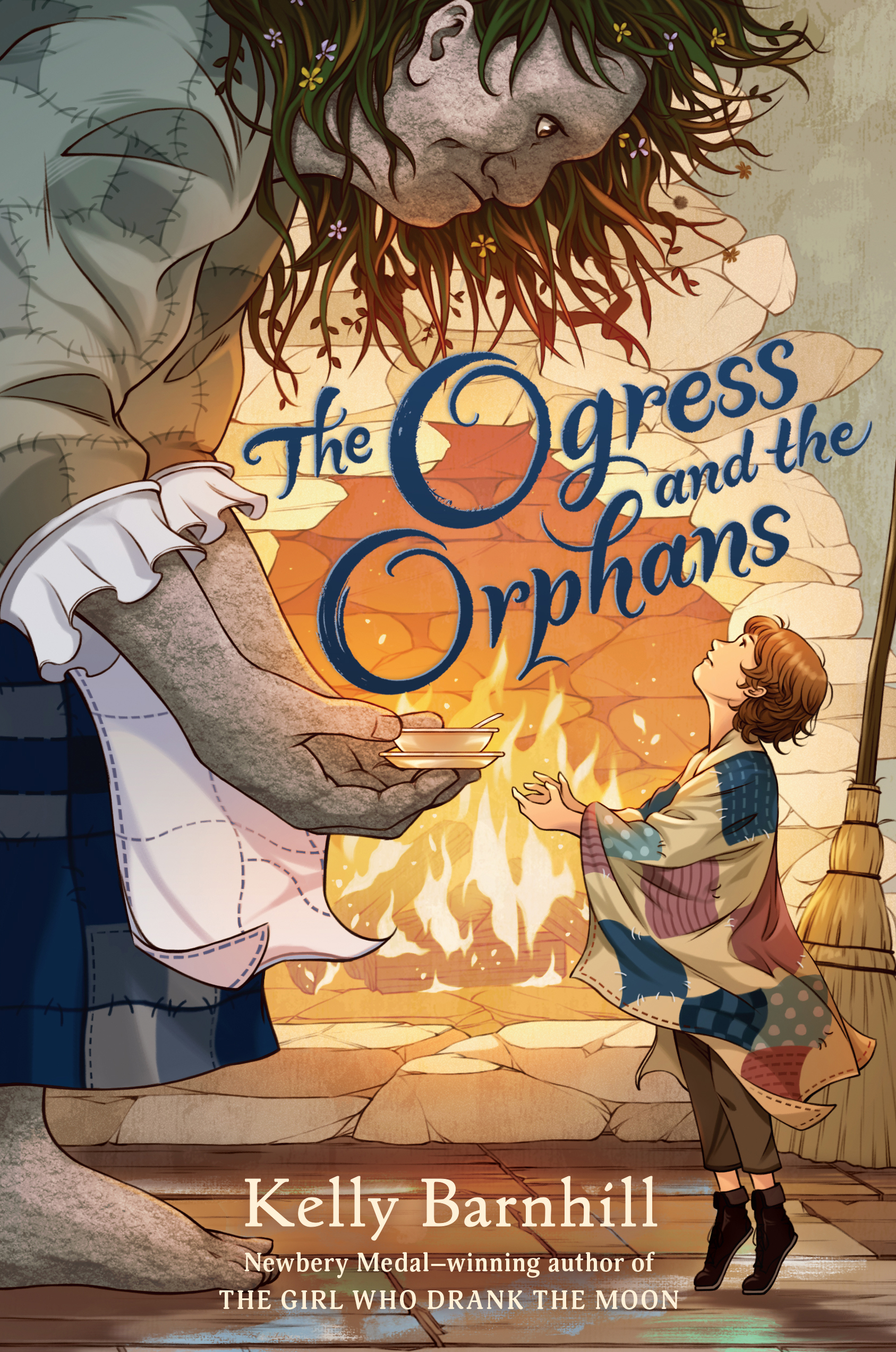

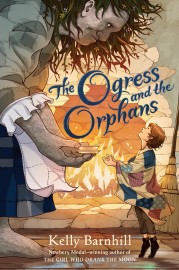

The Ogress and the Orphans

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.95Format

Format:

- Hardcover $19.95

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $10.99 $13.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 8, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

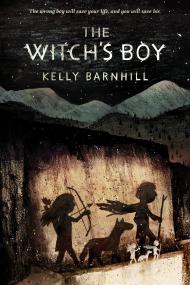

A National Book Award finalist and instant fantasy classic about the power of community, generosity, books, and baked goods, from the author of the beloved Newbery Medal winner The Girl Who Drank the Moon.

The town of Stone in the Glen used to be lovely, but it hasn’t been so in a very long time.Once a celebrated town with a vibrant town square, prosperous businesses and families, and educated, happy children, Stone in the Glen has fallen on hard times. Since the expansive and beloved Library burned with other buildings in a time of terrible fires, the town has been plagued by droughts, blight, and destruction.

But the people have continued to put their faith in the Mayor, a dazzling fellow with a bright shock of golden hair and brilliant white teeth who promises that he alone can solve their problems. And he is a famous dragon slayer! At least, no one has ever seen a dragon in the Mayor’s presence…

But somebody is to blame for the town’s problems, not only the fires and the decline that followed them, but the child who has gone missing from the local Orphan House. And with a little helpful suggestion from the Mayor, all eyes turn to the Ogress who has come to live at the far edge of town.

Only the children of the Orphan House know the truth. Together, they must clear the Ogress's name and solve the mystery of the town's destruction before their home of Stone in the Glen is destroyed by its own people.

Genre:

-

New York Times Bestseller

Shortlisted for the National Book Award in Young People's Literature

An Amazon Best of the Year honoree

“An exquisite fantasy tale … Whether you’ve been counting the months, weeks and days or are brand-new to Barnhill’s sharp, word-perfect prose and classical yet fresh storytelling, you’re going to love this standalone fantasy.

—BookPage, “2022 Preview: Most Anticipated Children’s Books”

“As exquisite as it is moving.”

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“The reader is immediately tossed into this fantasy … The Mayor is a fantastic (though loathsome) villain, oozing charisma and evil in equal measures … . It is fortunate that her tinkering with fairy tales and fables helped open a path to this novel that champions kindness in a very dark world.”

—Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books (starred review)

“Barnhill’s gift for storytelling immediately draws readers into this character-driven tale where dragons lurk, crows prove great friends, and an unusual narrator relays events with a unique perspective. These fairy-tale trappings cloak modern lessons and timeless ideals that readers will do well to take to heart, no matter their age.”

—Booklist (starred review)

Barnhill delivers a plea for empathy with deft charm...Deeply moving and often hilarious, The Ogress and the Orphans will encourage readers to live by the Ogress's adage: "The more you give, the more you have." —Shelf Awareness (starred review)

“Newbery Medalist Barnhill incorporates ancient stories, crow linguistics, and a history of dragonkind into an ambitious, fantastical sociopolitical allegory that asks keen questions about the nature of time, the import of community care, and what makes a neighbor.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A delightful tale with dragons, ogres, and orphans that is sure to have readers turning pages to see what happens next. … Characters from the town of Stone in the Glen are well developed and engaging. … Well written and engaging, this title is sure to please readers of all ages as it teaches valuable lessons on acceptance.”

—Youth Services Book Review

“Readers of all ages will love it. 5/5 stars.”

—YA Books Central

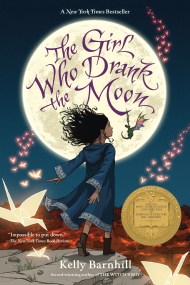

Praise for The Girl Who Drank the Moon:

2017 Newbery Medal Winner

A New York Times Bestseller

A New York Public Library Best Book of 2016

A Chicago Public Library Best Book of 2016

“Impossible to put down . . . The Girl Who Drank the Moon is as exciting and layered as classics like Peter Pan or TheWizard of Oz.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“A gorgeously written fantasy about a girl who becomes “enmagicked” after the witch who saves her from death feeds her moonlight.”

—People

“With compelling, beautiful prose, Kelly Barnhill spins the enchanting tale of a kindly witch who accidentally gives a normal baby magic powers, then decides to raise her as her own.”

—EW.com, The Best Middle-Grade Books of 2016

“Guaranteed to enchant, enthrall, and enmagick . . . Replete with traditional motifs, this nontraditional fairy tale boasts sinister and endearing characters, magical elements, strong storytelling, and unleashed forces.”

—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“Rich with multiple plotlines that culminate in a suspenseful climax, characters of inspiring integrity, a world with elements of both whimsy and treachery, and prose that melds into poetry. A sure bet for anyone who enjoys a truly fantastic story.”

—Booklist, starred review

“An expertly woven and enchanting offering.”

—School Library Journal, starred review

“Barnhill crafts another captivating fantasy, this time in the vein of Into the Woods . . . Barnhill delivers an escalating plot filled with foreshadowing, well-developed characters, and a fully realized setting, all highlighting her lyrical storytelling.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

- On Sale

- Mar 8, 2022

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781643750743

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use